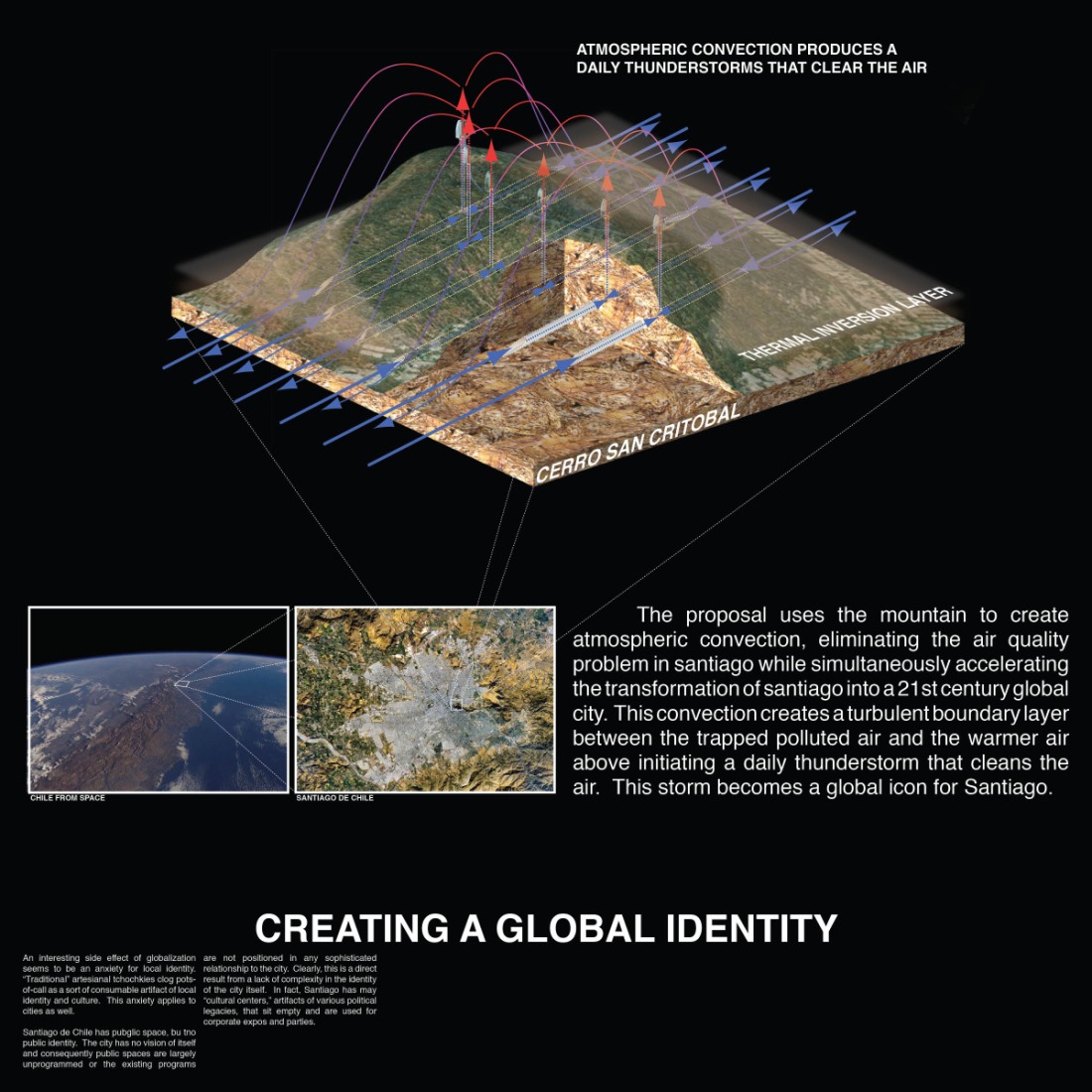

Creating a Global Identity

The proposal uses the mountain to create atmospheric convection, eliminating the air quality problem in Santiago while simultaneously accelerating the transformation of Santiago into a 21 st century global city. This convection creates a turbulent boundary layer between the trapped polluted air and the warmer air above initiating a daily thunderstorm that cleans the air. This storm becomes a global icon for Santiago.

An interesting side effect of globalization seems to be an anxiety for local identity. “Traditional” artisanal tchochkies clog pots-of-call as a sort of consumable artifact of local identity and culture. This anxiety applies to cities as well.

Santiago de Chile has public space, but no public identity. The city has no vision of itself and consequently public spaces are largely unprogrammed or the existing programs are not positioned in any sophisticates relationship to the city. Clearly, this is a direct result from a lack of complexity in the identity of the city itself. In fact, Santiago has many “cultural centers”, artifacts of various political legacies, that sit empty and are used for corporate expos and parties.

An Atmospheric Device

Parque Atmosfera proposes a lung for the city of Santiago that capitalizes on the height of Cerro Sancristobal to make an atmospheric device that serves as an icon for the city and for Chile in the 21 st Century.

A 21 st Century Lifestyle

Program, both in the tunnels and in the towers, is produced as the result of indeterminate actions on the part of the individual users of this structure. It is social by definition.

The towers organize the new park landscape as a set of vertical attractors that draw users in and up for recreation and leisure activities.

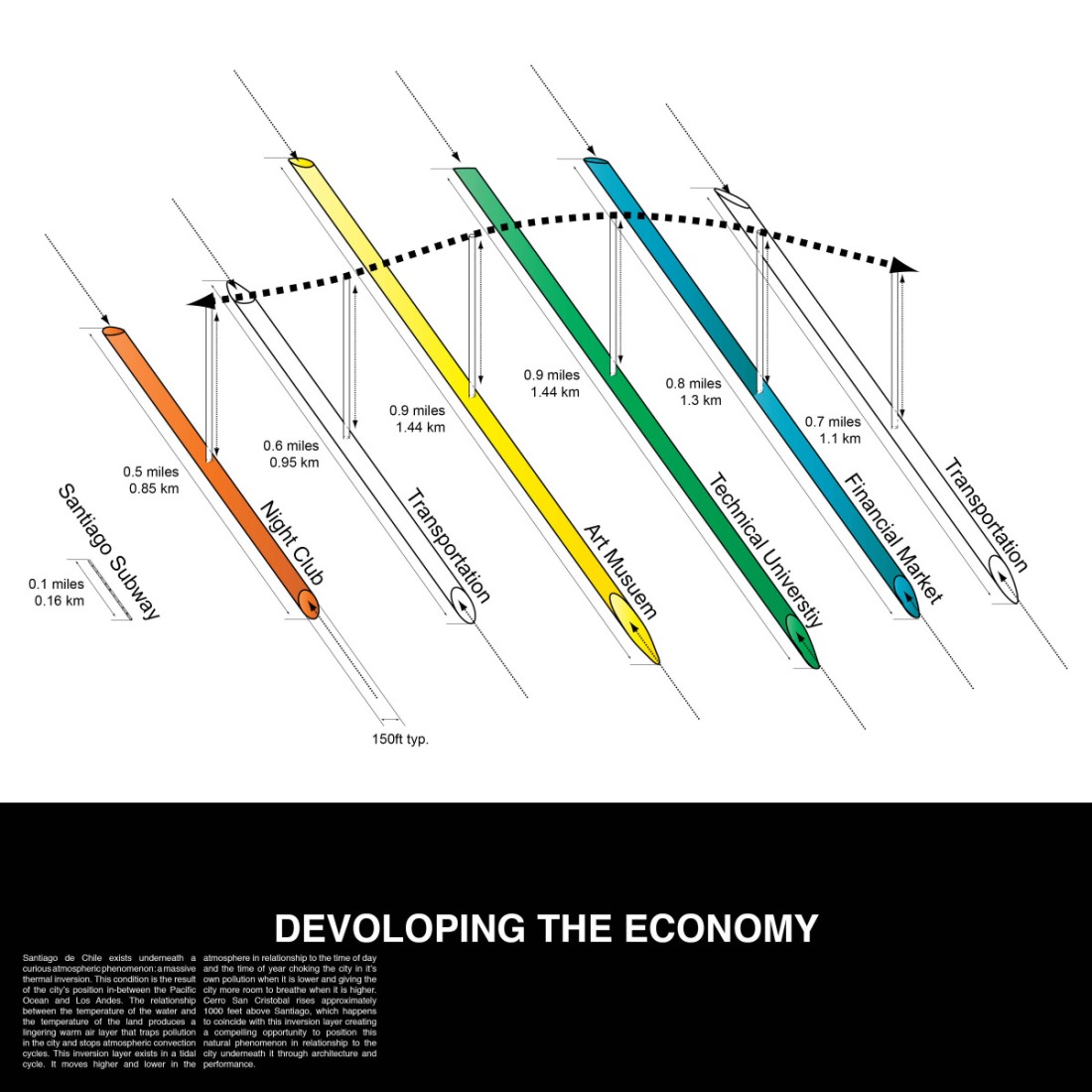

The tunnels each contain a facility that over time, will contribute to the de-polarization of the Chilean social sphere.

This proposal launches Santiago on the global stage by engaging Cerro San Cristobal, a site at the center of the city, the highest point in the city, and visible from everywhere in the city.

A Social Accelerator

Architecture cannot create a revolution; however, architecture possesses the ability to position technological and social revolution into situations people can understand, thus either accelerating or slowing such revolutions by helping or hindering the public’s ability to deal with change.

Unifying the city?

The mountain is the hinge of the city; it separates Santiago both physically and visually. This proposal seeks to stitch the city back together by reconsidering Cerro San Cristobal as a new center rather than a dividing element.

Santiago is a city of extremes. It has no mayor, but is a 6,6 million people agglomeration of 32 different municipalities and the Chilean federal government creating an extraordinary bureaucratic situation. Cerro San Cristobal fails fewer than 6 jurisdictions: the 5 communas that border ill, and the Federal Ministry of Housing. Looking out onto the city from a top the site, one sees two very different Santiagos. To the east is the city’s financial center with its skyscrapers and parks and to west are low-rise informal structures.

The mountain is the hinge of the city; it separates Santiago both physically and visually. This proposal seeks to stitch the city back together by reconsidering Cerro San Cristobal as a new center rather than a dividing element. Six tunnels stitch the city back together by providing additional methods of circulation through the mountain and by contain programs that accelerate the social and economic transformation of the city of the next 100 years.

Tensile Structures

A tensile system is used for the towers and the tunnels for both structural efficiency and as an emblem of the social tension produced by the two very different Santiagos on either side of Cerro San Cristobal.

Hung from the towers are a system of solar sails that can be deployed to enhance the venture effect in the system by warming the air with solar radiation to increase the air pressure differential between the towers.

It is a system for creating large-scale atmospheric convection in the San Cristobal hill in Santiago, Chile, mainly with environmental criteria.

More information

Published on:

October 23, 2010

Cite:

"OLD ROCKERS NEVER DIE" METALOCUS.

Accessed

<http://www.metalocus.es/en/news/old-rockers-never-die>

ISSN 1139-6415

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...