Ours is a time when art looks more and more like architecture, and architecture looks quite like art. Now rising at the 2012 Olympic Park is the Orbit, a pile of steel composed by the artist Anish Kapoor, which has things like lifts and stairs, serious engineering, and the scale of a building. Olafur Eliasson has just finished a spectacular glass wrapping to the Harpa Concert Hall in Reykjavik (When the Guest is better than the Author. Olafur Eliasson.) which has attracted a lot more attention than the parts by the actual architects of the project, Henning Larsen.

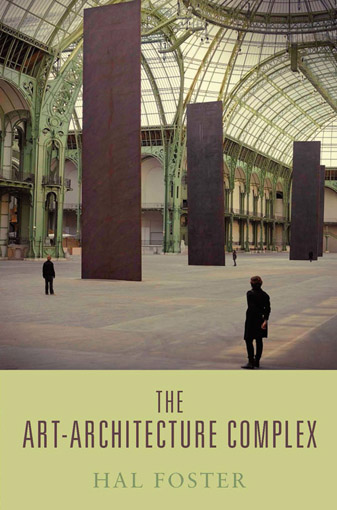

The Serpentine Gallery in London, a place dedicated to visual art, presents an annual pavilion, designed by an architect, as if it were the work of an artist, which is then sold to collectors. Architects themselves profess to be inspired, with varying degrees of credibility, by the likes of the American artist James Turrell. "Minimalism" has turned from an artistic movement to an architectural style to an interior design option. Office towers purport to be "sculptural", or else use tricks of perception borrowed from conceptual art. This co-mingling is the subject of The Art-Architecture Complex and, according to the book's author Hal Foster, it is "now a primary site of image-making and space-shaping in our cultural economy". As the half-sinister title suggests, with its echoes of Eisenhower's warnings about the military-industrial complex, and the suggestion of complexes in the psychological sense, the merging of art and architecture is not necessarily a good thing. It can become, suggests Foster, a means of blurring our consciousness, a new opiate of the people supplied by corporations and governments as they use "iconic" artworks and buildings to sell cities and property to investors.

He starts by taking us through major architectural movements of the last half-century, including the way pop art influenced both postmodernism and what became the hi-tech architecture of Richard Rogers, Renzo Piano and Norman Foster, which then led to a "global style" of steel and glass, more or less the same everywhere. In the case of Rogers, this global style takes the form of "pop civics" – law courts and assembly buildings and our beloved Millennium Dome, which profess accessibility and public engagement. In the case of Renzo Piano the result is "light modernity": elegant, refined structures that might be a Hermès store in Tokyo or a cultural centre in New Caledonia.

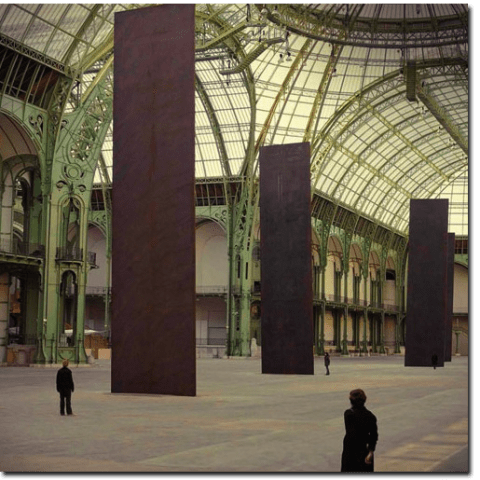

Foster describes the influence of Russian suprematist and constructivist art on Zaha Hadid, and the effect of conceptual art on the Americans Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the creators of New York's High Line park. Also, the use of both minimalism and pop by the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron, creators of Tate Modern and the Beijing Bird's Nest stadium. He then examines the question from the other side, looking at the spaces and constructions of artists like Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Robert Irwin and (especially) Richard Serra, before concluding with an extensive interview with Serra.

FULL ARTICLE IN The Guardian