Its urban landscape values are also different from those of the Western city. The Japanese urban structure developed according to the main role that Japanese culture gives to spontaneity, flexibility and the blurring in all aspects, the latter can be also observed in the built environment. Attention to fragments have always been prioritized over the consecution of a complete all with a defined limit.

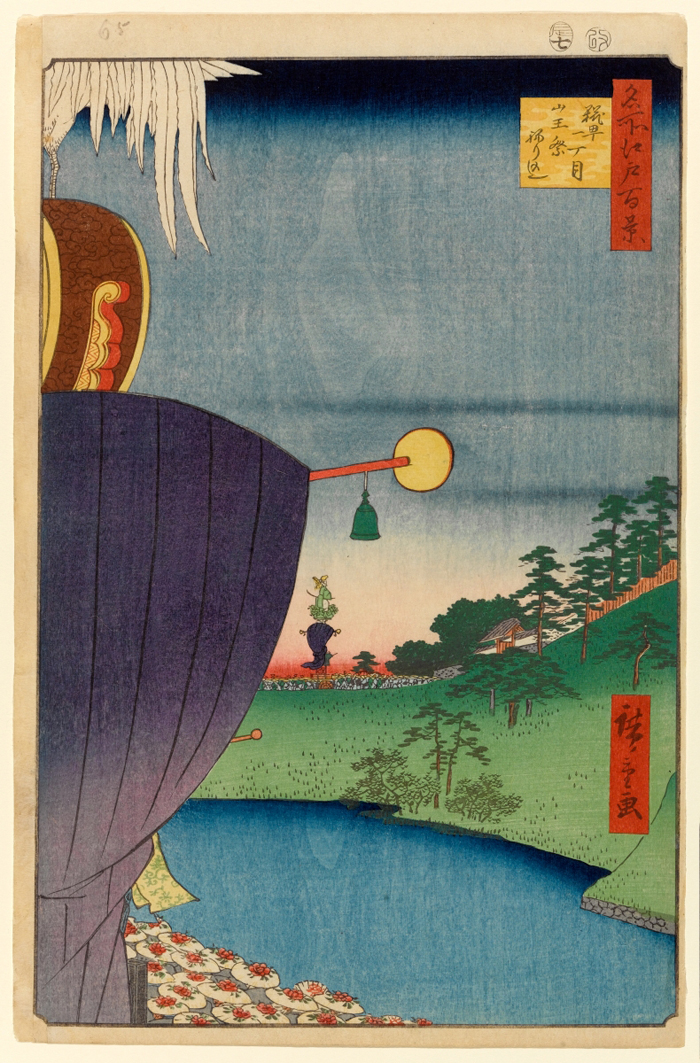

HIROSHIGE, UTAGAWA (1857). Cien famosas vistas de Edo. Nº 51 (Verano). La procesión Sanno en Kojimachi itchome. Xilografía a color. © Brooklyn Museum.

Logically, when the artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) faced to his series of work One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-1858) avoided a western representation of panoramic overviews and changed for an additive method of representation instead, consisting in the compilation of its more famous places. The image of the old Edo, origin of the actual city of Tokyo, seemed to have a more precise sense when it was represented as a sum of memorable instants no to be considered simultaneously.

HIROSHIGE, UTAGAWA (1857). One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. No. 81 (Autumn). Ushimachi in Takanawa. Color woodcut. © Brooklyn Museum.

HIROSHIGE, UTAGAWA (1857). One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. No. 99 (Winter). Kinryuzan Temple in Asakusa. Color woodcut. © Brooklyn Museum.

Thus, much of the interest of the series is set on the fact that it recreates the memory of some buildings or settlements of the city along the different seasons that can be considered as one after the other, as a consecutive series of images, assuring that the continuous remembrance of its memory.

Adding and removing the different elements of the architectural design, the Japanese house also adapts itself to seasonal changes, different uses and social needs. In this kind of spatial organization, the distinguishing elements generate a less predetermined combination of what you would think thanks to the flexibility in the connections between the parts. In turn, the group, understood as an aggregation or a group of elements ensures consistency of the fragments. In practical terms of this type of design, the exterior spaces play such an important role as the architectural objects themselves, as they create intermediate areas between them and the landscape.

Portrait of Hiroshige by Kunisada I. © Museum of Fine Arts. Boston.

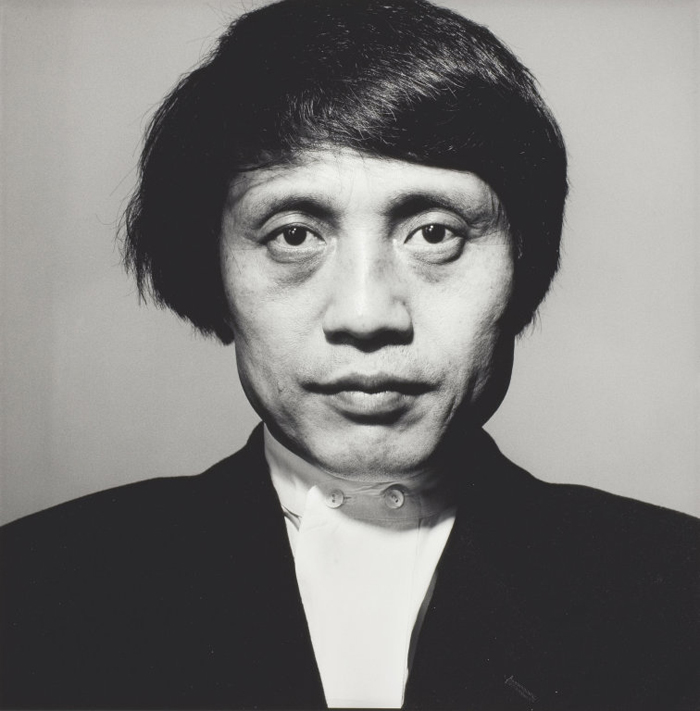

Tadao Ando in 1993. © The Irwin Penn Foundation.

In the buildings of the Japanese architect Tadao Ando (*1941) relations with the surrounding environment is expressed by a theory of dual character. The architect emphasizes the context in which a building originates. His work is definitely modern and therefore requires both, a method of an overall composition (a type that the traditional Japanese architecture has been unable to generate), and also provide another one in order to ensure the development of the individual parts. For that purpose, he introduces the architectural order based on a geometry whose key feature is the simple forms. Moreover, Ando attempts to answer the latent forces of the particular region where he is developing his work; and thus he carries out a theory of parts based on the sensitivity of the Japanese people (1).

Professor Felix Ruiz de la Puerta has confirmed how this Ando’s projective method reflects an additive composition of the space where the parts are incorporated into the overall structure, creating a composition in which both the whole as the fragments retain their own autonomy. These are complete in themselves and complement the whole. This conception of space allows us to define Ando’s work as 'an open architecture, ie, an architecture that enables the modification thereof by future enlargements' (2).

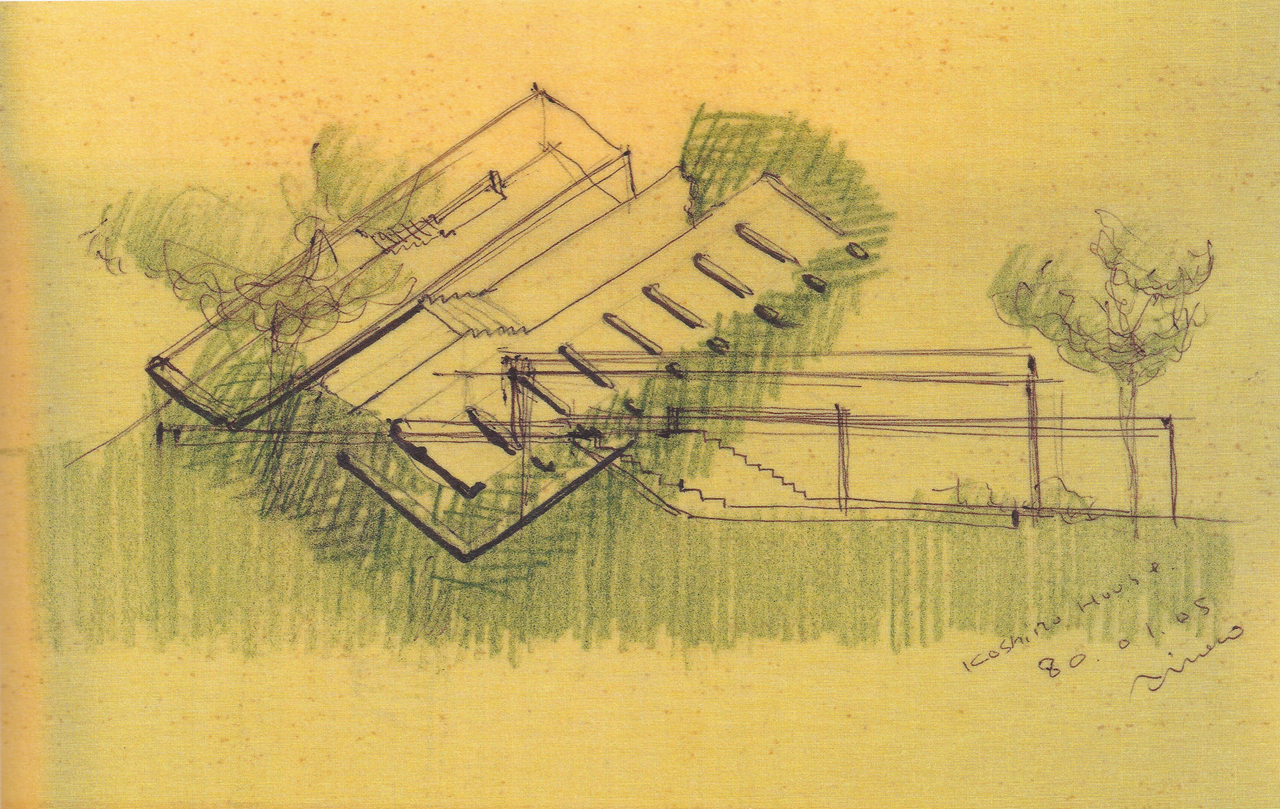

ANDO, TADAO (1979-81). Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). Sketch. © Tadao Ando, Architect & Associates.

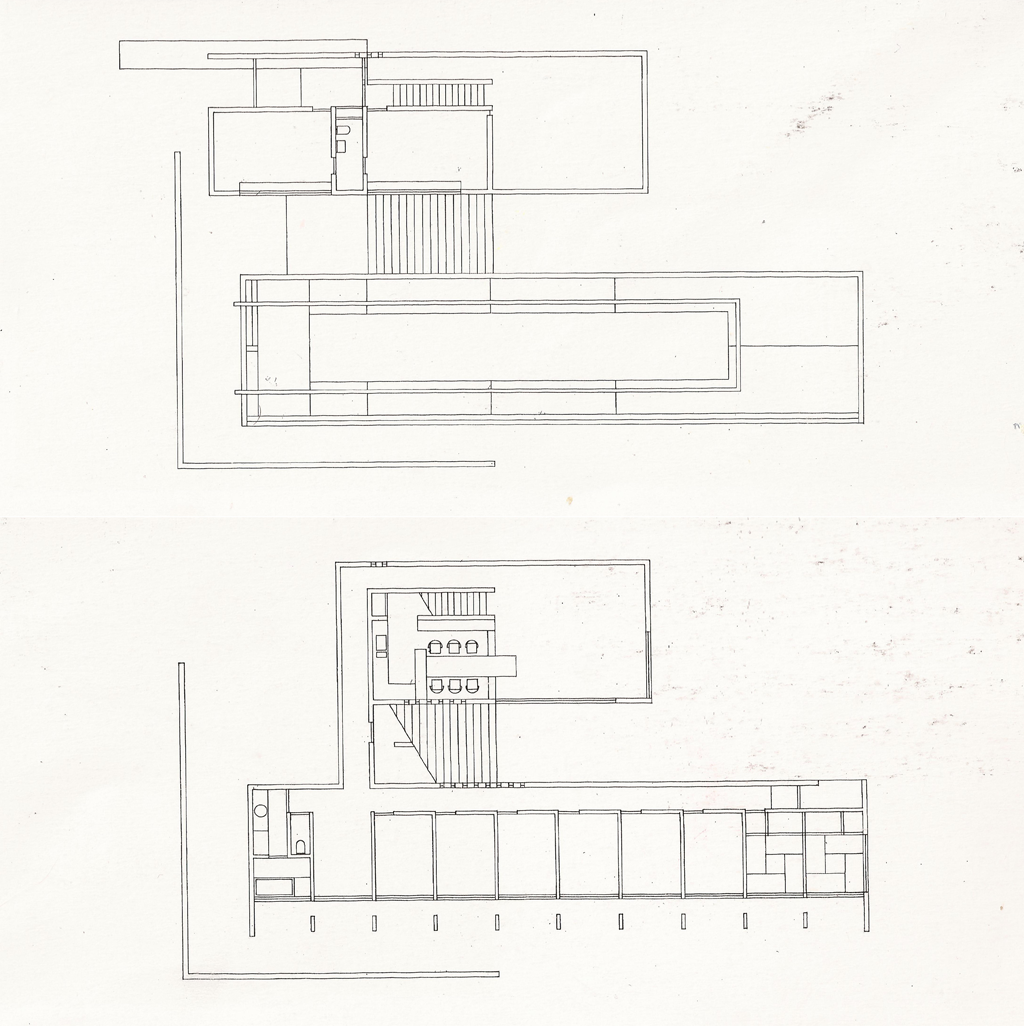

The 2009 documentary entitled "Tadao Ando / The Koshino House" by the Finn director Rax Rinnekangas (* 1954) reveals the house as a collection of fragments of Ando’s architectural vocabulary. The original composition of 1983 met two boxes of different lengths in the mountains of Ashiya (Japan) which, arranged in parallel, relied on the slope one after the other and joined by a courtyard that saved the level difference by incorporating a stands.

ANDO, TADAO (1979-81). Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). Ground floor plan and first floor plan. © Tadao Ando, Architect & Associates.

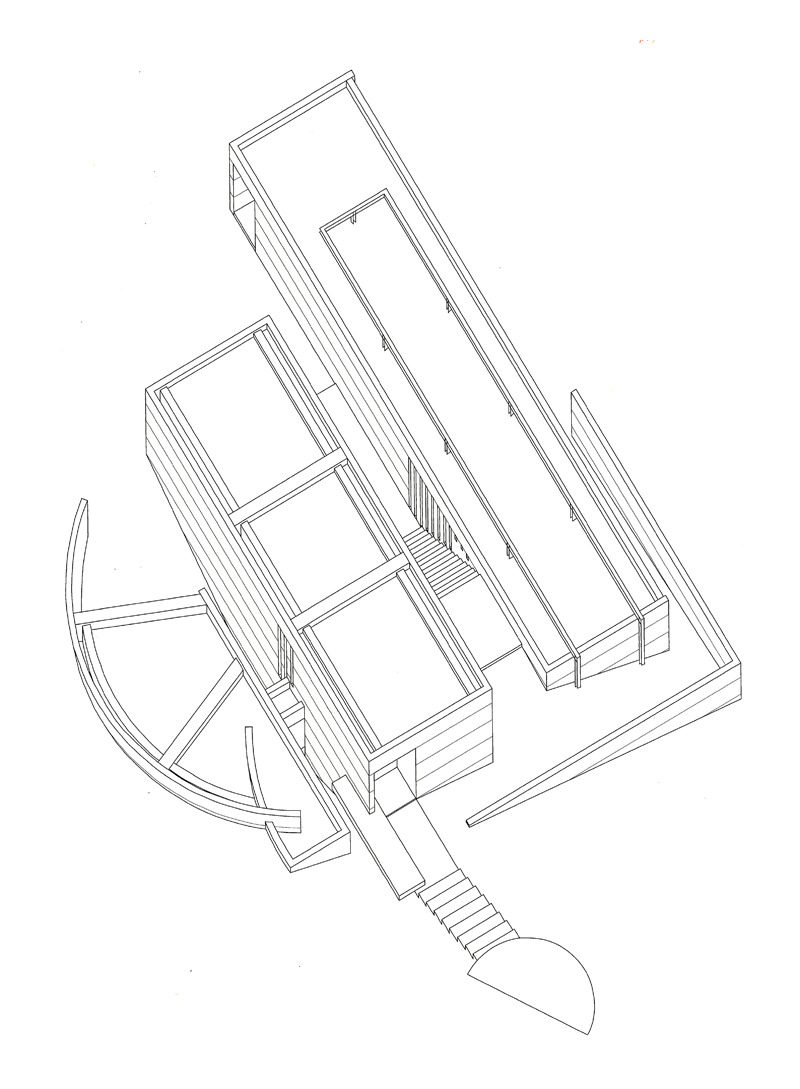

ANDO, TADAO (1984). Workshop of Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). Axonometry. © Tadao Ando, Architect & Associates.

Three years after the completion of the initial order, fashion designer Hiroko Koshino transmitted the need to incorporate a study to the architect. Despite that complete and perfect concept that Ando tries to make apparent in the overall design of his works, when the nature of what exists is stronger than what could be built instead, renovations and expansions are presented as the right direction to follow.

In contrast to the linear composition of the existing parts, the addition to the house consisted of a wall against the ground that ran fourth in circumference and appropriated a new space half buried on the top of the slope. A slit running down the wall was solved with a skylight, where the incoming light offered complex patterns on the curved surface at intersections, as opposed to the rectilinear patterns of light in the original building. Finally, the strong contrast that this addition suggested in the compositional method only reinforced the architectural unit in this house (3).

ANDO, TADAO (1984). Workshop of Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). © Tadao Ando, Architect & Associates.

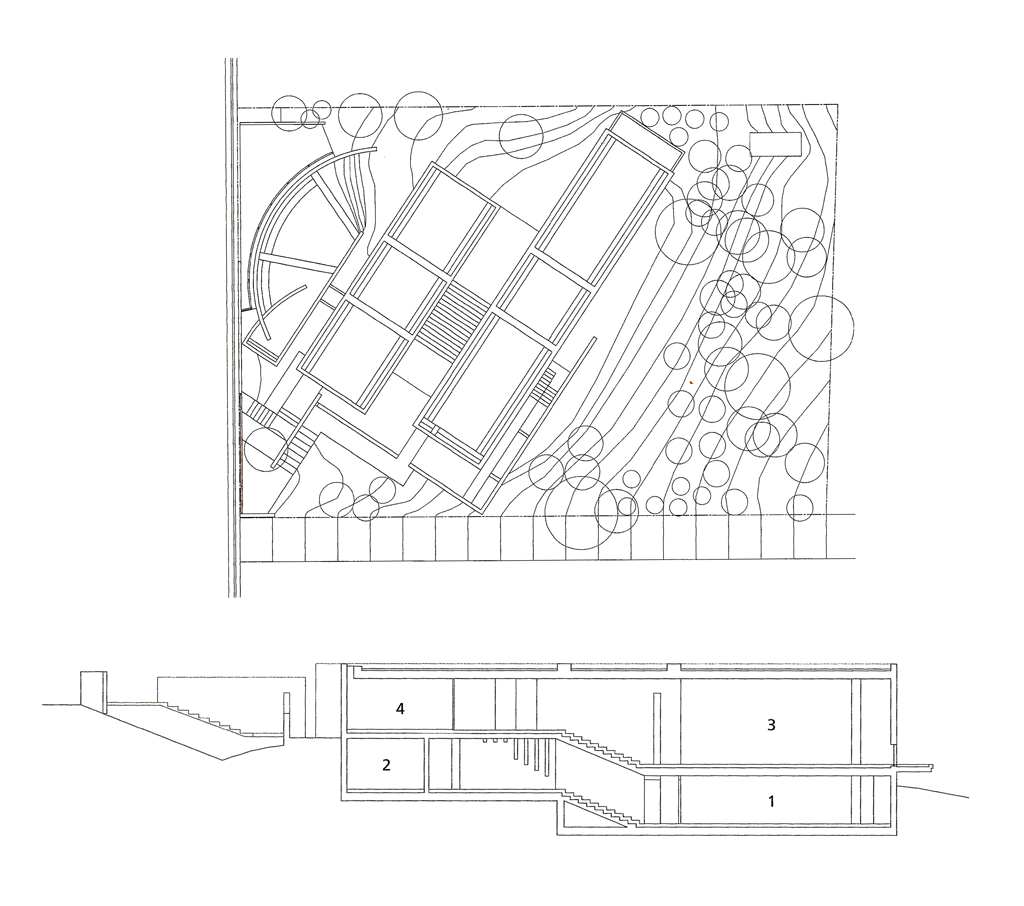

ANDO, TADAO (2004-06). Guest pavilion for Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). Site plan and longitudinal section. © Tadao Ando Architect & Associates. 1. Cloakroom. 2. Bedroom. 3. Hall. 4. Room with tatami.© Tadao Ando Architect & Associates.

Twenty years after the incorporation of that study, the owner asked Ando the task of renewing the south bedroom wing of the house, since her children were grown and rarely used it. This part of the house was reinvented as an independent two-storey guest house.

ANDO, TADAO (2013). Gallery Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). Views from inside the main room. © Hiroko Koshino Co., Ltd.

In the personal conscience of the architect and for practical purposes of spatial composition the construction was a finished building, however Ando once again backed its sketches in order to understand it as a place in which the existing buildings were included (4).

With the help from the architect, the owner has turned the building into an art gallery nowadays where she can collaborate with worldwide artists and support young talent artists. The KH Gallery in Ashiya (2013) has a concentrated atmosphere so that visitors can enjoy the artworks in a museum alike architectural framework. Visitors to the gallery who complete the tour will found the kitchen area and the original dining room, both with the original layouts preserved.

ANDO, TADAO (2013). Gallery Koshino House. Ashiya (Japan). Views from inside the main room. © Hiroko Koshino Co., Ltd.

The constant evolution of this house does not seem to have weakened its central themes neither its impressive architectural presence. Japanese writer Fukuyiro Wakatsuki (1881-1927) narrated how one of the favorite games of the poets of his country was to compose half uta (thirty one syllable poetry) and pray someone else to completed it. Similarly, in Ando’s conception, leaving the work unfinished could mean the path to eternity, trying to comprehend it through a way of expression that has not closed its finite boundaries and that way it aims to identify the object and its environment.

NOTES.-

(1). ANDO, TADAO (1982). From self-enclosed Modern Architecture towards universality, en DAL CO, FRANCESCO (1995). Tadao Ando. Complete works. London: Phaidon, p. 446.

(2). RUIZ DE LA PUERTA, FÉLIX (1995). Lo sagrado y lo profano en Tadao Ando. Madrid: Álbum, Letras y Artes, p. 108.

(3). ANDO, TADAO; EISENMAN, PETER; FRAMPTON, KENNETH and KUNIHIRO, GEORGE T. (1989). Tadao Ando: the Yale studio & current works. New York: Rizzoli, pp. 30-31.

(4). ANDO, TADAO (2007). Tadao Ando 1. Houses & Housing. Tokio: Toto, p. 162.

(5). WAKATSUKI, FUKUYIRO (1926). Le Japon traditionnel. París: Au Sans pareil (versión castellana de M. Perales (1939). Tradiciones japonesas. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe), p. 23.