This was not the case with Wright. With him, one is left without a road map. His holistic approach, the immensity of his concerns and discoveries, the breadth of his formal repertoire, diversity of materials, colors, textures, ornamental details, structural and conditioning solutions, and especially the relationship with the site and the environment, sharply contrast with any reductionist approach where elements are limited, restricted, or excluded. The inclusion of references to Japanese architecture, Chinese ornamentation, and allusions to Mayan and other Native American cultures completes the statement and dispels any preconception of what is available to us. These non-Western influences on Wright's work were probably the first in modern architecture, and perhaps the main reason for disdain among many contemporary architects. He is as free as a bird, but with his feet always ready to firmly grasp the ground or a branch, only to take flight again.

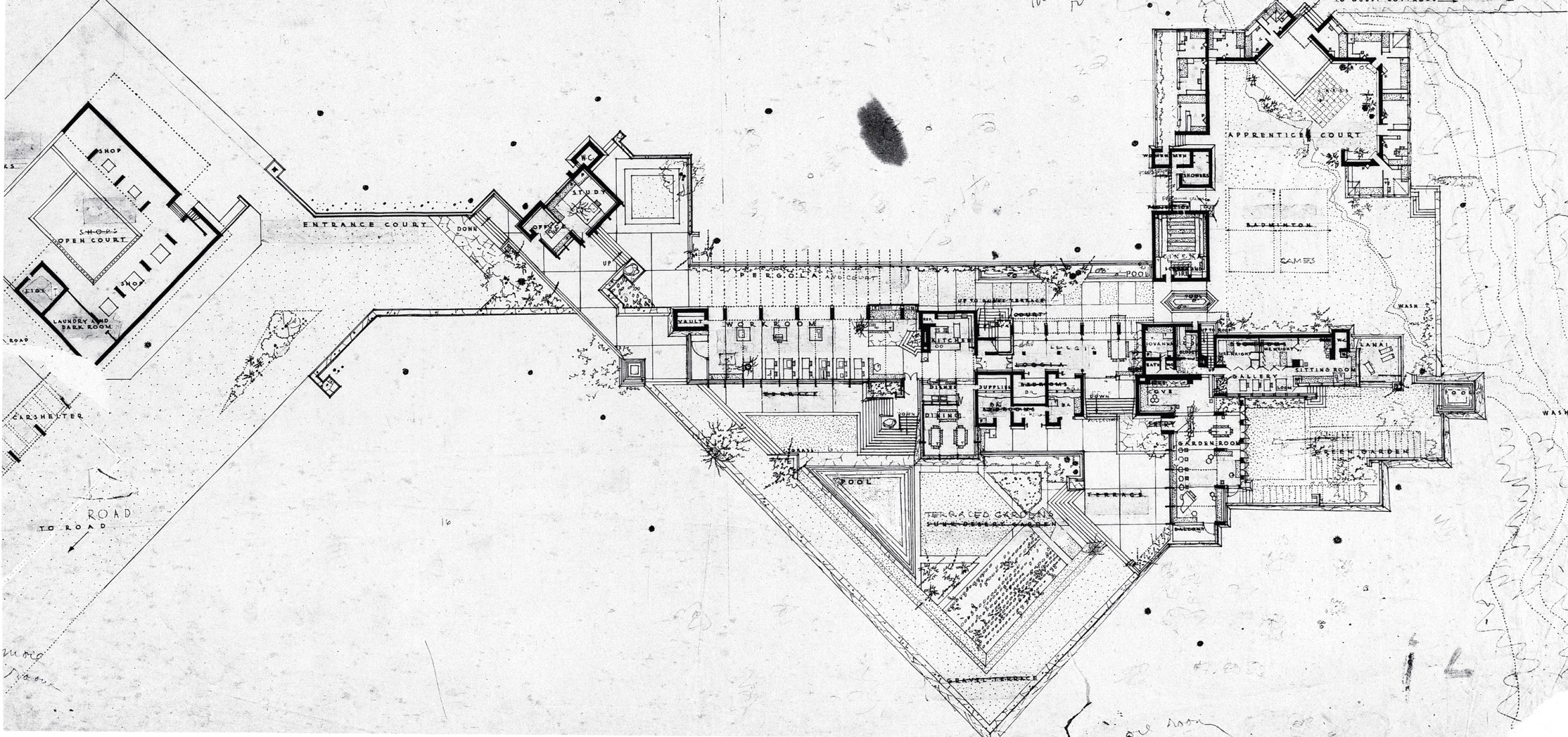

Let's recall some dates: Wright and his apprentices began construction of Taliesin West in 1937 and continued working throughout the 1940s. At that time, Europe and European ideals were under attack, as the greatest war in history ravaged the continent. After the war, Western culture would never be the same; a new world was born, much broader, more decoded, less philosophical, and less secure.

Taliesin West by Frank Lloyd Wright. Photograph by Lucas Rios Giordano.

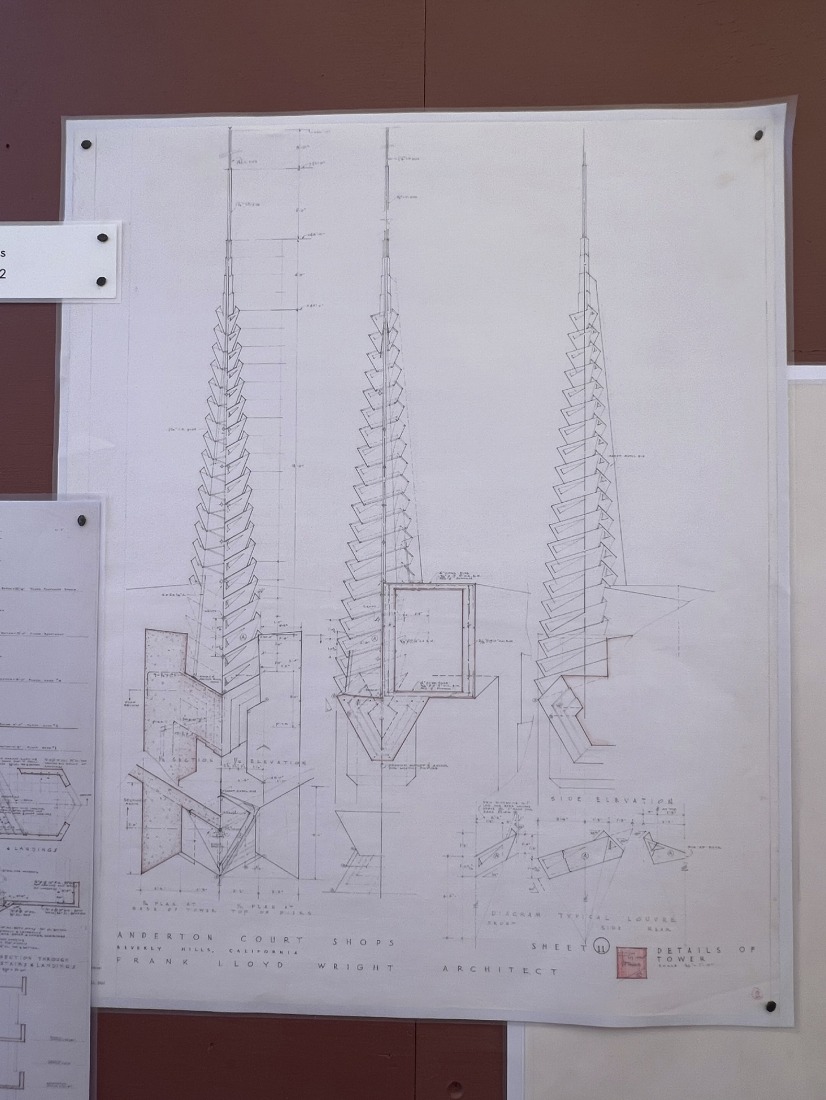

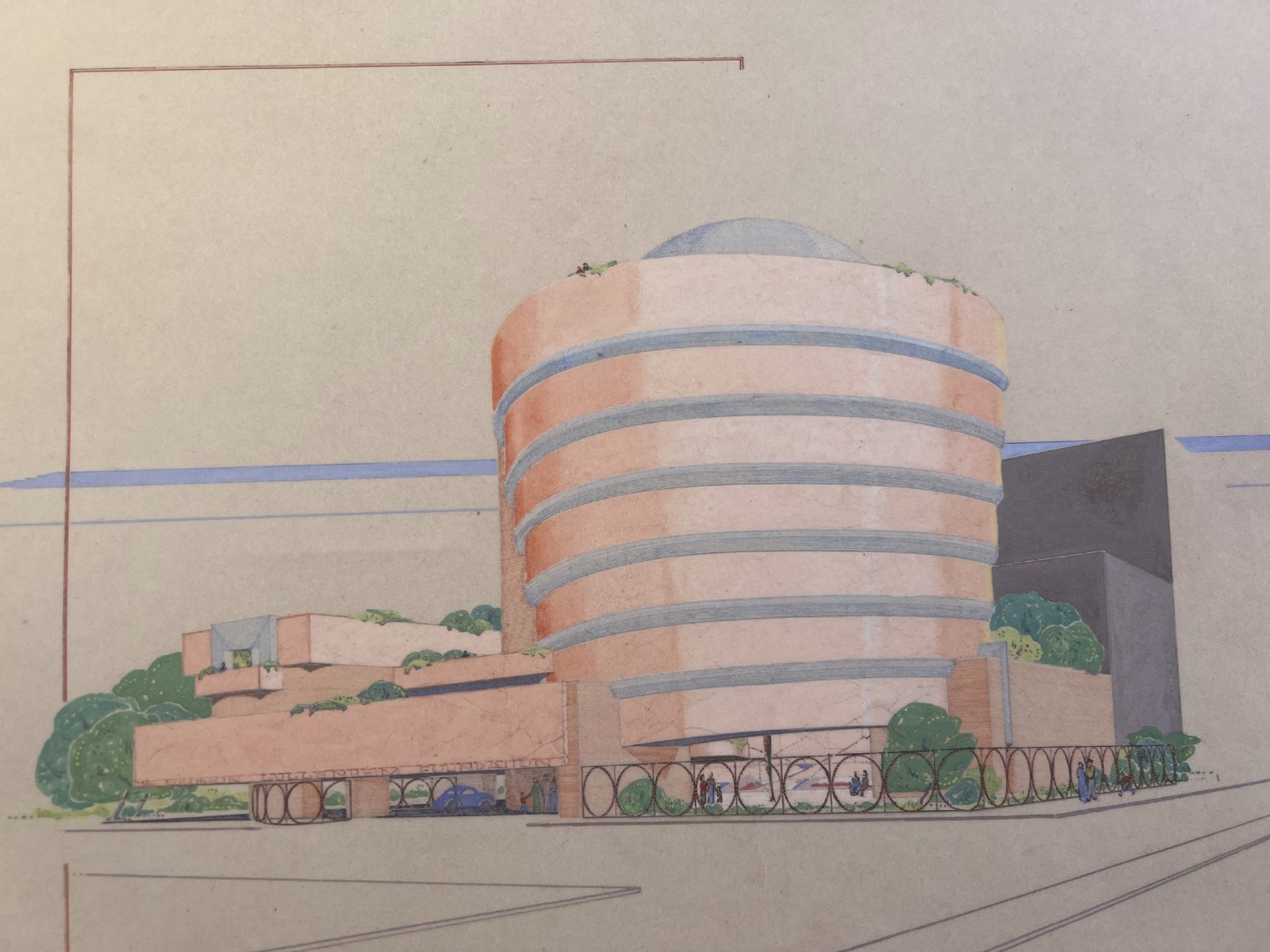

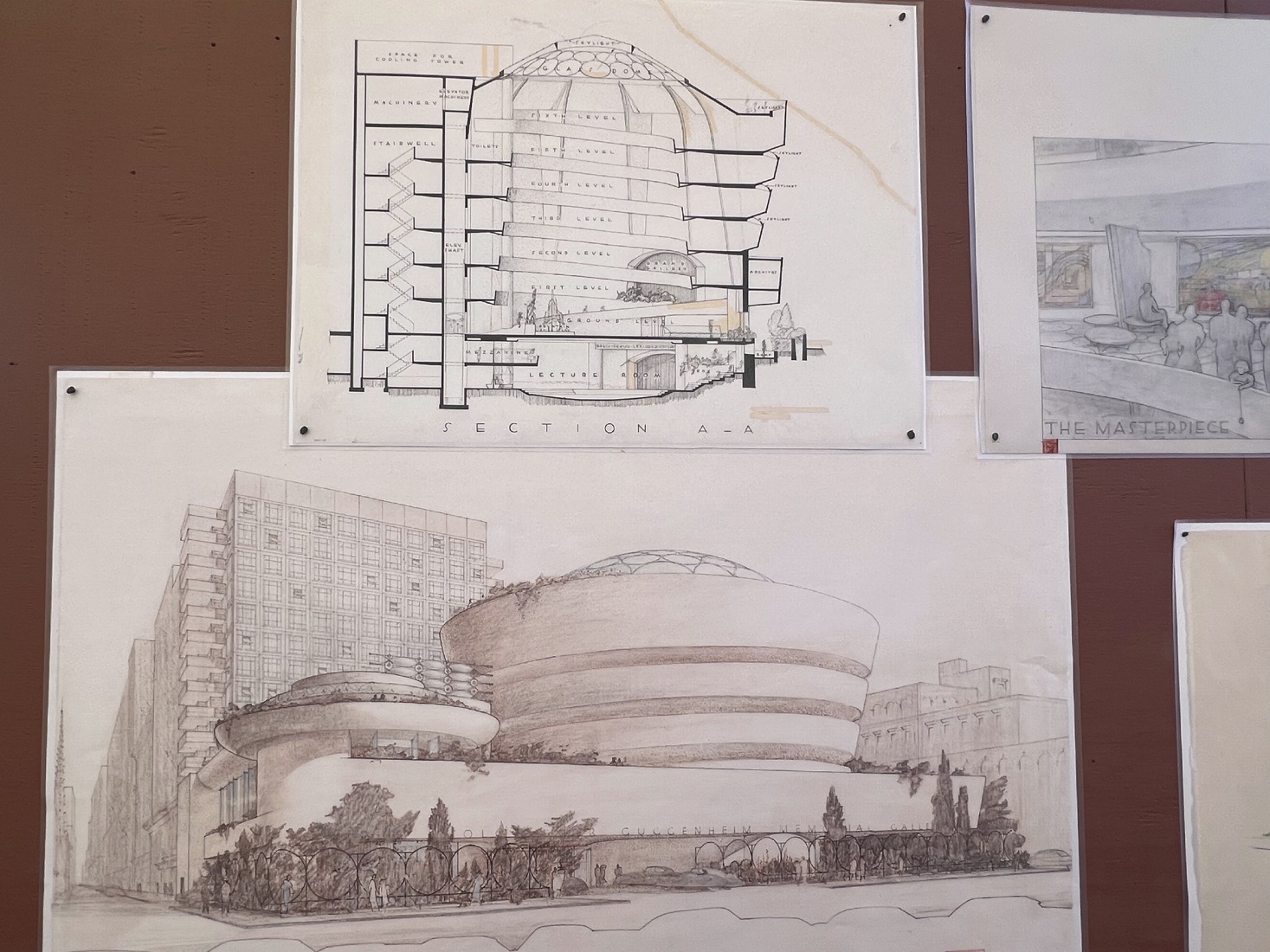

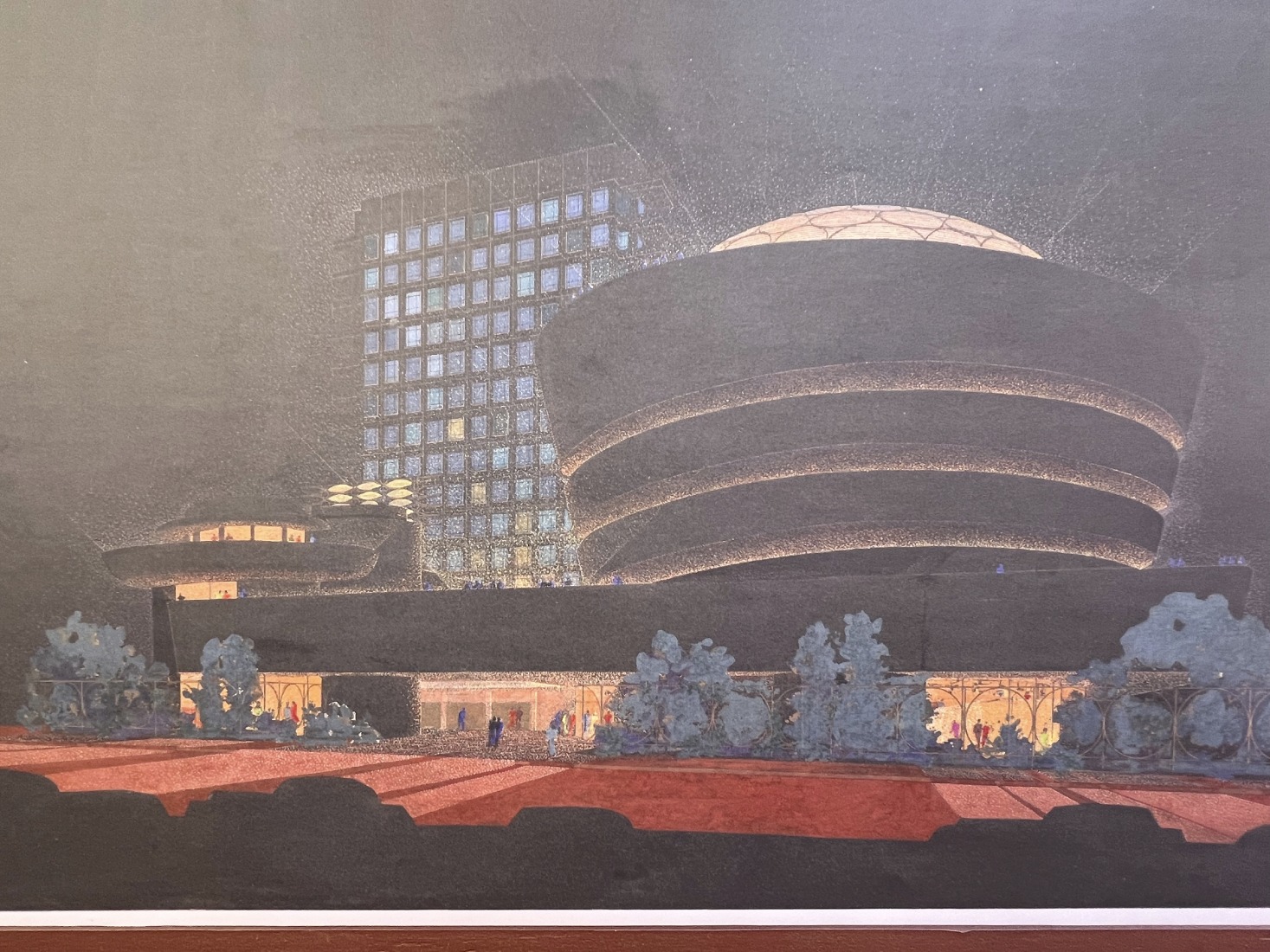

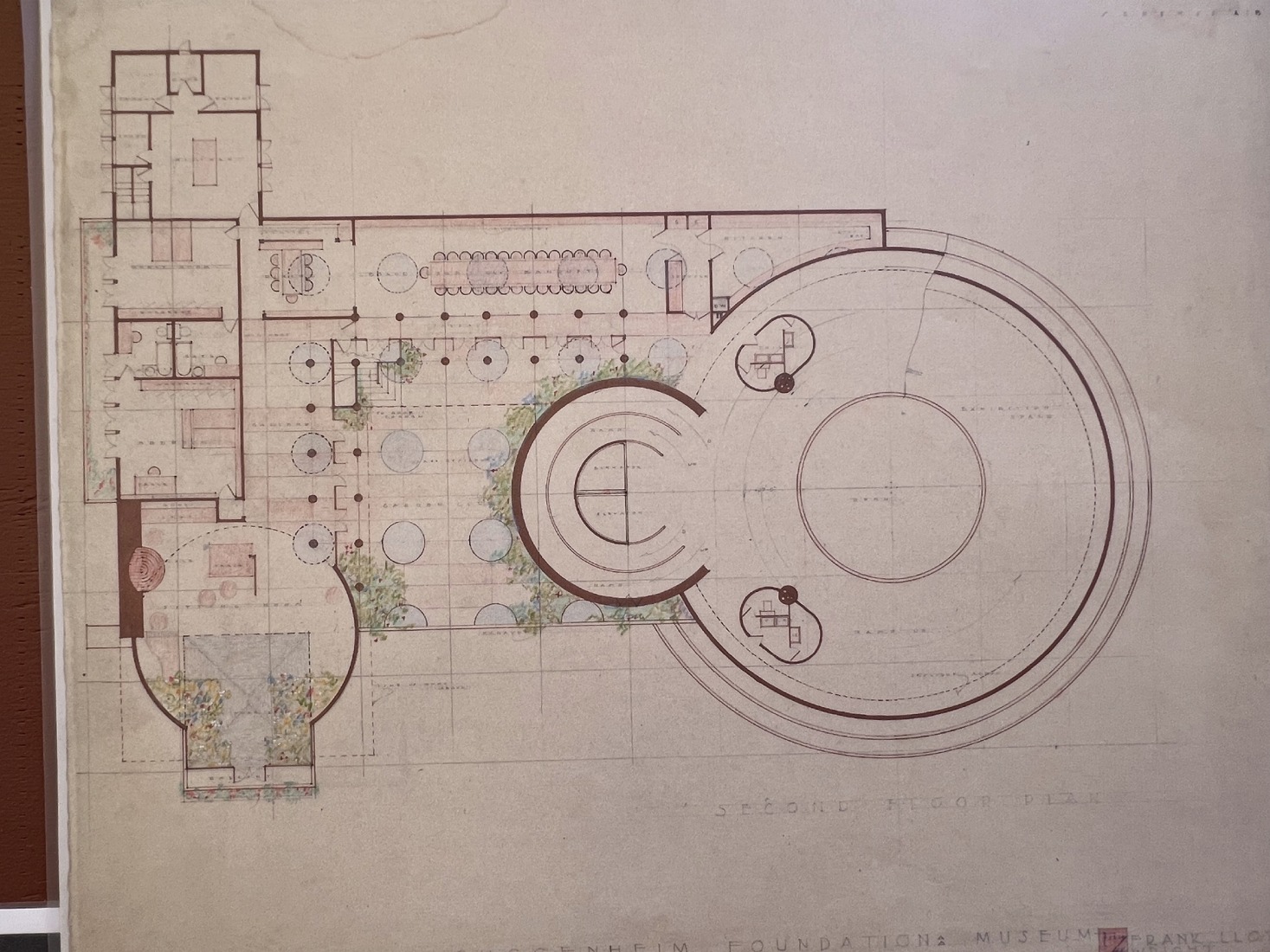

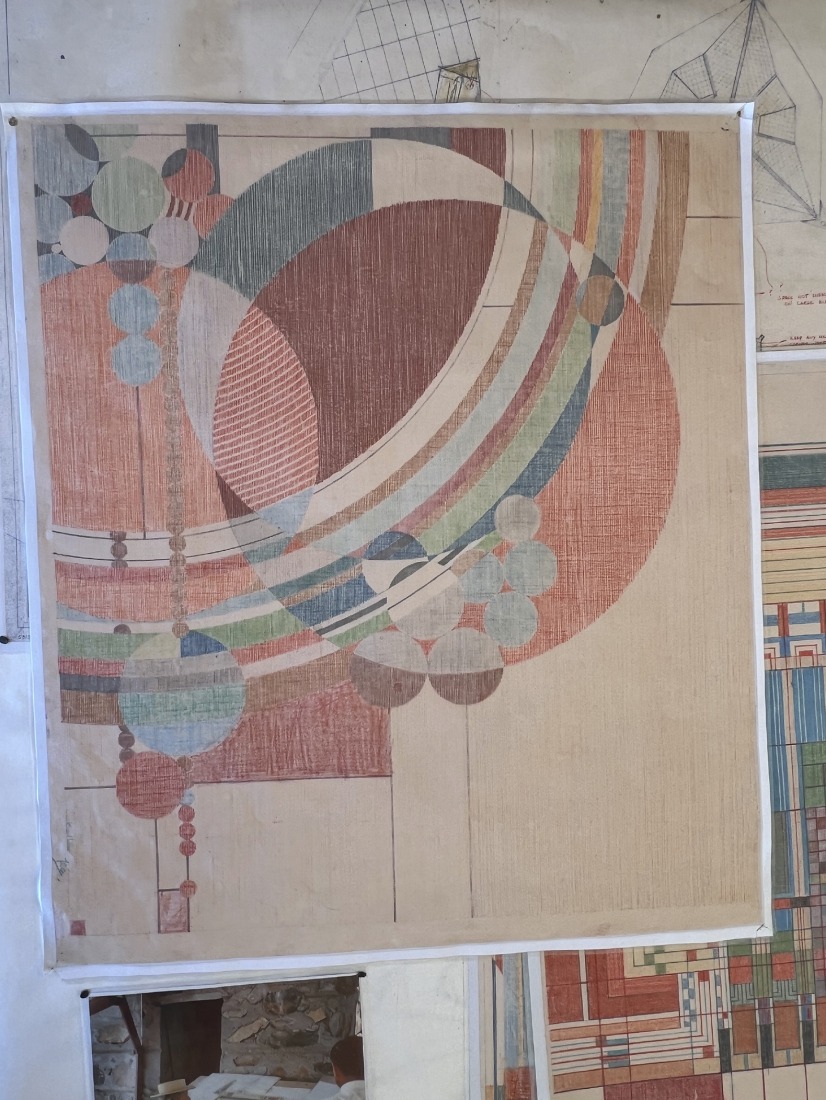

It has been argued that Wright's architecture left no followers or school. It is true that, apart from a few practitioners—including two sons whose work resembles his—there is no main school. However, could it be said that there is an indirect influence in a broader sense that persists to this day, and might even become predominant? I am considering the opening of endless formal possibilities that perhaps began with him. He started working on the design of the Guggenheim Museum in 1943, precisely at Taliesin West (Several original drawings with idiosyncratic approaches can be seen there). Could this mark the beginning of a tradition that validates any form? Ronchamp, designed in 1953, comes to mind. Scharoun's Berlin Philharmonic in 1963, to name two. In California, there has recently been much experimentation in the work of architects such as Eric Moss and Morphosis. Frank Gehry combines formal freedom with technological advances, similarly to Wright. However, none of these architects' work exhibits the range of ideas and concerns that Wright embraces, nor do they represent the vast diversity of our world today.

I would like to conclude with a brief digression on political significance. Wright was a popular architect, building homes for wealthy industrialists and middle-class people, but his architecture was never elitist. Whether one liked it or not, everyone could "understand" it. His architecture was concrete, not abstract, and he was unafraid of what might be considered "bad taste," thus encompassing a broad cultural spectrum. This contrasted with the practice of most of his modernist contemporaries, who, while building "for the masses," often conveyed condescension in their message. In today's world, characterized by troubling division, cultural antagonism, and resentment toward elites, Wright is an inspiration for finding ways around the ongoing culture wars, on whose resolution our very survival depends.

Taliesin West by Frank Lloyd Wright. Photograph by Lucas Rios Giordano.

Far away, in the Arizona desert at the beginning of the 20th century, someone anticipated and offered clues to our future today, 90 years later. Far from being an oddity, a lone cowboy fading into the distance, like in a John Wayne movie, Frank Lloyd Wright’s work may be more relevant than ever, especially at Taliesin West. In the desert, among snakes and scorpions, Wright became the most visionary of all.

Lucas Rios Giordano.

Los Angeles, May 2025.