In its classical conception and according to the dictionary definition, mimesis is the “imitative representation of the real world” as the essential aim of art. Plato viewed the mimetic world as inherently subordinate to its original or its idealization, whereas Aristotle already deemed mimesis as a tool through which we interpret reality. Much later during the Enlightenment, mimesis was again scorned as the science of rational thought sought its dominance over nature.

With the dawning of the 20th century, thinkers such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno and Jacques Derrida rekindled the debate on the term conferring on it a more creative, interactive role. In the hands of Benjamin, mimesis becomes a process of reciprocal assimilation between the subject and the external world, forging links and establishing a form of empathy between them. In artistic practices, this seeking out of similarities leads to the creation of representative images, in day-to-day life mimesis intervenes as we strive for greater social integration, while under extreme circumstances, it becomes a defence mechanism in what we call camouflage.

The rough scaly skin of the chameleon, with its impressive colour changes, becomes invisible when danger looms as it camouflages into the surroundings, as a leaf for example. In this guise, the chameleon dissolves or blends into the environment. It ceases not to exist, but remains quietly perched upon a branch in a heightened state of tension. In the face of danger, though not seen, the chameleon continues to exist.

Nature creates similarities. One need only think of mimicry. The highest capacity for producing similarities, however, is man’s. His gift of seeing resemblances is nothing other than a rudiment of the powerful compulsion in former times to become and behave like something else [emphasis added]. Perhaps there is none of his higher functions in which his mimetic faculty does not play a decisive role. (1).

The processes at play in architectural design deploy a whole array of responses when facing the built environment, all of which involve some degree imitation; imitating the immediate environment, models or typologies used as ideological references. Thus, they involve varying degrees of mimesis. In these responses lies a desire to exist in the world, to feel connected and to organise ourselves in relation to it. In the words of Benjamin, there is a powerful compulsion in these processes to become like the world around us and, in some way, to find our place and belong to it.

For this text I have brought together two architectural designs interspersed between three photographic collections with a view to exploring how imitation and mimesis intervene in all five in a unique yet comparable manner. As mimesis is invariably present as part of the creative process, I have selected examples where the degree of dissolving into the environment appears compelling. On such occasions, the complexity of the relationship between the body, clothing, architecture and landscape ends in a kind of technical stalemate in a game of mutual assimilations, where players work in unison while at the same time losing some of their individual integrity. In this new context of intimacy, art work becomes specific and contingent.

Body and Architecture

Both body and architecture exist insofar as they occupy a place. The architectural form abandons its autonomy as an object in order to exist in function of the relationships it forges with its surroundings, and to the extent that it becomes the environment. However, this assimilation of the architectural space by the body produces in both, body and space, a loss of autonomy. The blurring of these boundaries is resolved in an essentially creative way, where the body and architecture mutually assimilate each other: the body becomes space and the space becomes the body. We can only truly comprehend a particular identification with a landscape or dwelling through the similarities or mimesis established between them.

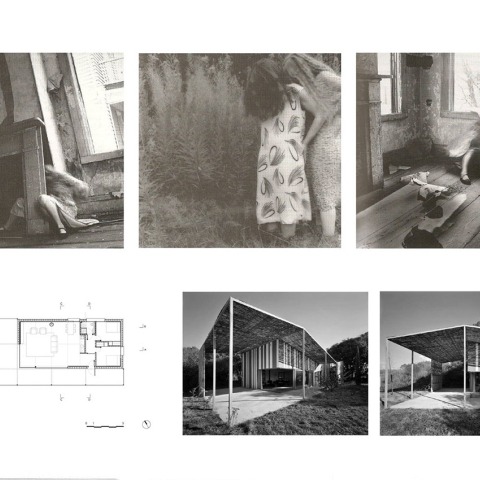

The photographs below were published in an exceptional book called Camouflage (2) by the English critic and architectural theorist Neil Leach. Leach obtained permission from Francesca Woodman’s (3) parents to publish 18 photographs taken in Providence (Rhode Island), Stanwood (Washington), Rome and New York between 1975 and 1980. In his book, Leach explores the notion of camouflage through a psychoanalytical reading of how we relate to where we live. Freud, Lacan, Kristeva and Zizek, as well as Benjamin and Adorno, are all used by Leach to develop his manifesto on how architecture relates to its surroundings, its deep interweaving with the body and the concept of being in the world.

Caption 1.- Rome, May 1977 – August 1978. The photo shows a woman’s body nude from the waist up revealing her breasts and stomach. The lower wall is painted to the height of the dress, with the peeling paint echoing the pattern on her dress. The unpainted wall matches the woman’s skin thus horizontally aligning both background and body. Both the body and space appear covered under a veil of dust and neglect as they engage in a process of mutual dissolution.

Caption 2.- Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1976. A woman crouches down to hide behind an old mantelpiece which has partially become detached from the wall. The mantelpiece, leaning against the wall between the woman’s splayed legs, appears phallic and the hearth and now extinct fire are evocative of the heat of sexual exchange. Again, the body and architecture are matched, equivalent, locked in a mutual assimilation process.

Caption 3.- Stanwood, Washington, summer 1979. The photograph is taken in the natural setting of a marshland in Washington state. Two female bodies, one standing behind the other, touch slightly, their faces hidden behind their long hair falling nonchalantly like a weeping willow. Their secluded posture blurs the lines between their hair and their floral print dresses. They are standing knee-deep in the water with their bodies merging with the fertile water. Beside them, great ferns grow and become anthropomorphic-like as the figures become elements of the landscape.

Caption 4.- House #3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1978. The model is now sitting beneath an open window. The long exposure time traces her movements, making her body appear almost ghostly from which fragments of the wall and wall-paper seems to emanate and scatter on the floor. The dilapidated state of the building tells of a tragic and desperate assimilation, as if the building were exposing its fury having being humanised by and through the dissolution of the figure.

Caption 5.- New York, 1980. In this final photo, just the top of a woman’s head appears out over the edge of a cast iron bathtub with a cascade of blonde hair overflowing the edge of the empty tub. The claw-feet and great round swelling shape of the huge white tub appear like a great feline creature as if trapped midway during its transformation from object to body.

Woodman unveils the complexities of the relationship between the body and architectural spaces. Her photographs portray the intimacy of this relationship and do not shy away from highlighting the arduous struggles. On contemplating the photographs, one perceives that the greatest intimacy between body and architecture also involves a mutual disconnect, an irreversible estrangement. The melancholic poignancy of these prints may well lie in this intimate discord hinted at through Woodman's images.

Architecture and Landscape.

The house is small with a rectangular floor plan, consisting of a living room, a small kitchen, a bathroom and two bedrooms. Nothing out of the ordinary. No typological innovations; perhaps one of the most useful remnants of postmodern times is the reinstatement of the architectonic types. This house, aligned with an existing house in the small village of Gaüses (Girona, Spain) and designed by the architects Anna and Eugeni Bach, rests upon the western end of a flat south-west facing plot. Like the neighbouring house, the Gaüses house is in direct contact with the garden as a single storey construction.

The roof is sloped, with a concave inverted gable (butterfly) design. The rainwater collects in the valley, runs along the gutter to a monumental gargoyle that spouts it out in a parabolic curve to fall splashing into a cylindrical tank below. This water is then used to irrigate a small adjoining garden. The roof is ventilated, following the more traditional Catalan flat roof style, with small vents along the two short facades.

Apart from the slightly inclined roof, the house is parallelepiped. The brick walls are load-bearing, except on the western side where a slender cylindrical metal pillar allows the entire corner to be opened up, with large sliding doors embedded into the walls that disappear when open. During the long warm seasons, the house and the garden become one continuous open space. The northern and western facades are painted in vertical white and dark green stripes. The stripes are of different widths and the distances between them also follow an uneven pace.

Attached to the main structure is a lightweight metal frame that serves as a porch. Like an artificial prosthesis, this squared-tubed metal structure extends the volume of the house towards the garden, completing the longitudinal profile to that of a more traditional Catalan farmhouse (masia) with a ridge roof line. The metal structure is painted grey and covered with a thin layer of river cane. The lines defining the porch are pale and slender which creates a virtual effect that extends right across the entire building dissolving all tectonic connotations of the thick load-bearing walls.

The cane roof confers an even greater sense of virtuality upon the surroundings. On side view, the longitudinally-cut cane appears very thin, while the frontal view allows a certain degree of transparency, filtering the view. As the sun rises, the cane projects irregular shadows that dance across the facades. The garden trees and shrubs, including the nearby cypress, also cast their arboriform whispering shadows to the rhythm of the characteristic local winds.

This complex play of shadows on the facade of vertical stripes dilutes the tectonic dimension of the house pushing it ever closer to virtuality. To a certain degree, the house fades into the garden. There, the architecture remains (like the chameleon) locked in a process of dissolution, in a state of permanent tension with its undeniable presence. And it is precisely here in this state of dialectical tension wherein lie the poetics of this small house in the village of Gaüses.

English translation.- Angela Frawley.

NOTES.-

(1) “Nature creates similarities. One need only think of mimicry. The highest capacity for producing similarities, however, is man’s. His gift of seeing resemblances is nothing other than a rudiment of the powerful compulsion in former times to become and behave like something else. Perhaps there is none of his higher functions in which his mimetic faculty does not play a decisive role”. Walter Benjamin, “On the Mimetic Faculty”, Reflections (1933), New York: Schocken Books, 1986.

(2) Neil Leach, Camouflage, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006.

(3) Francesca Woodman was born in Boulder, Denver, in 1958 and died in New York City in 1981. Born into a family of artists, her childhood and teenage years were spent between Boulder and the Italian Tuscany, where her family spent their summers. She later studied Art, Design and Photography in Providence, Rhode Island and also, with the aid of a grant, in Rome. She finally settled in New York where she lived for about three years before ending her own life. Her artistic legacy, managed today by her parents, consists of approximately 10,000 negatives and some 800 prints. Woodman used a medium format camera producing 2-1/4 by 2-1/4 inch (5.7 x 5.7 cm) square negatives. Only 120 of the 800 prints have been made public.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.-

Image 01-05.- Francesca Woodman: Roma, May 1977 – August 1978. (02) Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1976. (03) Francesca Woodman, Stanwood, Washington, verano de 1979. (04) House #3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1978. (05) New York, 1980.

Images from the book, Neil Leach, Camouflage, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006.

Image 06-10.- Anna & Eugeni Bach, Gaüses House perspective. (07) Ground floor plan. (08-10) Photography (Jordi Bernadó)

Images courtesy of Anna & Eugeni Bach.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-

Walter Benjamin, “On the Mimetic Faculty”, Reflections (1933), New York: Schocken Books, 1986.

Neil Leach, Camouflage, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006.