Yu Ting ultimately chose to carry out the intervention on the former aquatic base in the bay, with the constraint of being very careful, not altering the existing vegetation "even a millimeter" and preserving two existing buildings. In addition, the client requested the reuse of some ceramic panels.

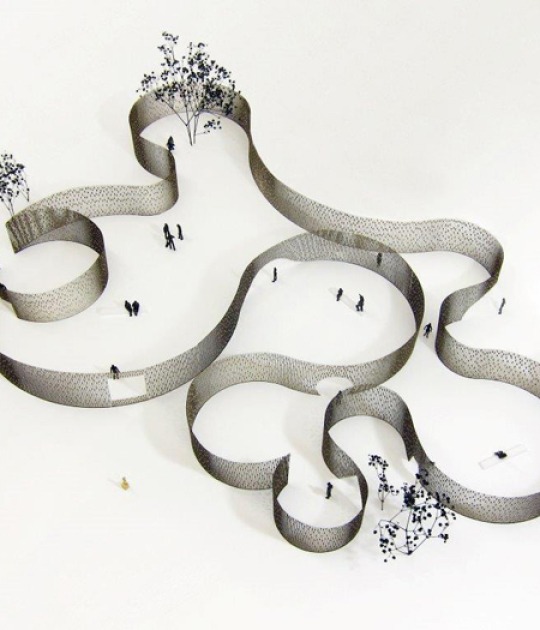

Wutopia Lab approached the project with one of the defining characteristics of his work, "house within a house": two buildings wrapped respectively in a metallic and a ceramic skin. The metallic shell acts as a climatic boundary, while the ceramic skin serves solely as a visual layer.

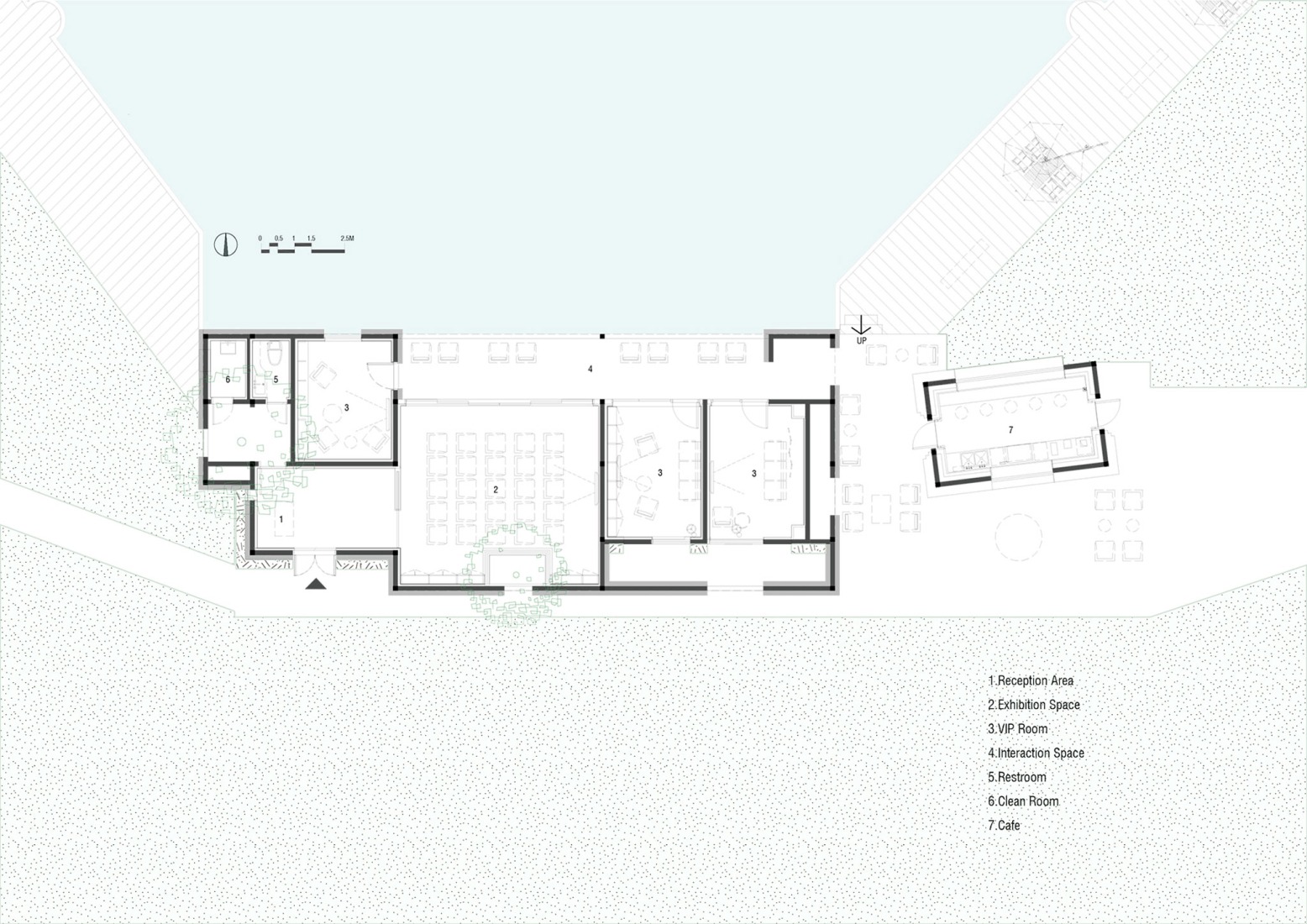

The project was created with the idea that the user feels that their views of the park are a process of constantly unfolding different perceptions. The project proposes different horizontal layers of light and shadow, embraces the trees without touching them, and organizes a program composed of the lobby, the exhibition hall, three uniquely themed VIP lounges, the willow-lined colonnade, the terrace, the riverside promenade, and the café in a composition that creates a sequential, habitable, and walkable journey.

The Lake House – Life Experience Pavilion by Wutopia Lab. Photograph by Guowei Liu.

Project description by Wutopia Lab

On April 18, 2025, The Lake House – Life Experience Pavilion, designed by Wutopia Lab at the commission of CSCEC Jiuhe East China Region, officially opened in Daning Park, Shanghai.

Part I: Working Diary

On February 28, Chief architect YU Ting was invited to survey three potential sites in the park and select one for the new pavilion. Representatives from the client’s design, engineering, and marketing departments, the construction company, and the park authority were all asked to join the visit. The park was to clarify the redline boundary, construction restrictions, and time limitations. The design department was to assign point persons for architecture, structure, and interior coordination. Engineering and construction teams needed to assess the site conditions, define the material supply chain and structural methods feasible within 40 days, and the marketing team was to provide usage programs, circulation plans, and curatorial requirements.

Based on all this, YU proposed a comprehensive design—architecture, interior, landscape, soft furnishing, and exhibition—aimed at achieving completion and public opening by April 18.

The final site chosen was the former water base by the bay. The only restriction from the park was to preserve the structures of two existing buildings and not disturb even a millimeter of surrounding greenery, including two trees abutting the façades. Meanwhile, the client hoped to incorporate ceramic curtain wall panels previously used in residential developments.

That same evening, YU applied his signature “house within a house” design strategy: two buildings were respectively wrapped in a metal and a ceramic skin. In a video call with structural consultant MIAO Binhai, they confirmed the feasibility: the metal shell would act as the climate boundary, while the ceramic skin would serve purely as a visual layer. The existing structure would retain its insulation and waterproofing.

YU passed his sketches and notes to project architect Liran SUN.

Part II: Concept

In an interview, I said that Chinese people have a persistent attachment to nature—even when surrounded by concrete and steel. This sensibility makes us treasure even those things others discard. That’s why this pavilion uses ceramic panels, recycled tiles, marine plastic plaster, marine plastic panels, mushroom leather, and light to form an undercurrent—a zero-carbon narrative that lies beyond light and space. It reflects a core cultural belief: to cherish. From this, we move toward zero-carbon living and a beautiful life.

On February 28, standing on the bridge and seeing the site, Wright and Mies reawakened in my mind. It was the horizontal line—like a Chinese scroll unrolling. In our aesthetic tradition, a beautiful life is framed through landscapes, gently unfolding across the horizon. Even when the scroll ends, the scene continues in our imagination.

Using horizontal layers of light and shadow, I organized the preserved trees, vertical greenery, lobby, exhibition hall, three uniquely themed VIP rooms, willow-lined colonnade, terrace, boardwalk, and café into a linear spatial journey—inhabitable, walkable. The boundaries between inside and out dissolve. Orientation is gently disoriented, not in fear, but in delight. In these fleeting, sacred moments, one suddenly feels the emotional clarity of Chinese culture revealed in the everyday.

In VIP Room 1, you can sit and gaze at a window that becomes a living painting. The skylight above disperses quietly across you and me. Words fail.

I originally wanted a staircase under the skylight as a lookout, but the park didn’t allow it. We kept the skylight anyway. It now recalls old Shanghai tiger windows, or contrasts with the nearby tree hole as positive and negative space. It was not part of the original design—just improvisation. And isn’t that the charm of Chinese design? Controlled surprise within a plan.

On opening day, a passing elderly man reached out and gently touched the pearlescent ceramic wall. He stood for a long while, then smiled and walked away. That moment—was beautiful.

Space is Spirit

We once believed that material wealth defined a good life. Now, we realize a smile, a restrained surprise, or a moment of clarity on a sunny afternoon is the real beauty.

In that instant, architecture is no longer form or narrative—but spatial drama. In a place that can host “peaceful ambition,” we experience a brief sacred moment. And in that moment, life reveals its truth.

Architecture exists to capture that moment of beauty.

At Wutopia Lab, we live for that moment—fleeting yet timeless.