"Rock dreams" was called in The Village Voice, to the exhibition in the Guggenheim entitled: "The Sparkling Metropolis." An event that was not exempt from the typical irony that characterizes Rem Koolhaas: “The irony wasn’t lost on me,” remembered the opening day, about the fact that Frank Lloyd Wright, the Guggenheim’s architect, hated cities.

In the same space, and a drastic switch in topics the show, “Countryside, The Future,” (opened this week during six-month), spilling out of the Guggenheim’s front door, there is a huge Deutz-Fahr tractor, remotely operable by iPad, parked outside, on Fifth Avenue. An iconic reference to welcome wisitors to exhibition.

Rem Koolhaas and OMA’s think tank, AMO, led by Samir Bantal, explore radical change in the world’s non-urban territories, a five-year long research project with thesis of "to put the countryside on our agenda again".

The exhibition, which occupies the entirety of the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed rotunda, uses the building’s architecture to tell a story that unfolds as visitors ascend the famous spiraling circulation route.

"It's a show about sociality, anthropology and politics."

Koolhaas takes no clear political position on many of the hot-button topics the show raises, portraying himself as a reporter not pundit, realist not cynic, equally amazed and appalled, refusing moral judgments or virtue signaling.

In 2007, a dozen-odd years ago, the United Nations announced that this is the first urban century, the first time more than half the world’s population lives in cities. Predictions were that some 70 percent of humans will be urban-dwellers by 2050.

The show explores living, producing, and designing in the countryside: the 98% of the world's surface (oceans included) that does not make up its 2% of cities. The countryside is explored as a historical concept in ancient societies, as well as through the varying attempts to build planned countrysides in socialist countries, through new food and energy production methods, through land conservation, through climate change, and through off-the-grid living in examples across the globe from Chile to Japan or from Soviet Union to Qatar.

Koolhaas traces the roots of the exhibition to walks that he took years ago around the Swiss village near St. Moritz where he and his partner and sometime collaborator, the British-born Dutch architect Petra Blaisse, used to holiday. He noticed the population dropping, the town growing; cows, horses and farmers giving way to immigrant domestic workers from Southeast Asia and absentee owners from Milan who spent millions of euros converting old barns into minimalist villas.

The show includes no buildings by OMA. The designer of the Seattle Public Library and the national library in Qatar, among other recent landmarks, makes clear that this exhibition is not about his architecture.

“Countryside” unspools along the rotunda montage-style, ideas and eras speeding by, figures unearthed like the German architect Herman Sörgel who, during the 1920s, cooked up a scheme to link Africa with Europe by lowering the Mediterranean 100 meters, irrigating the Sahara and installing new hydroelectric dams in Gibraltar and Suez to power the new continent, which he called Atlantropa.

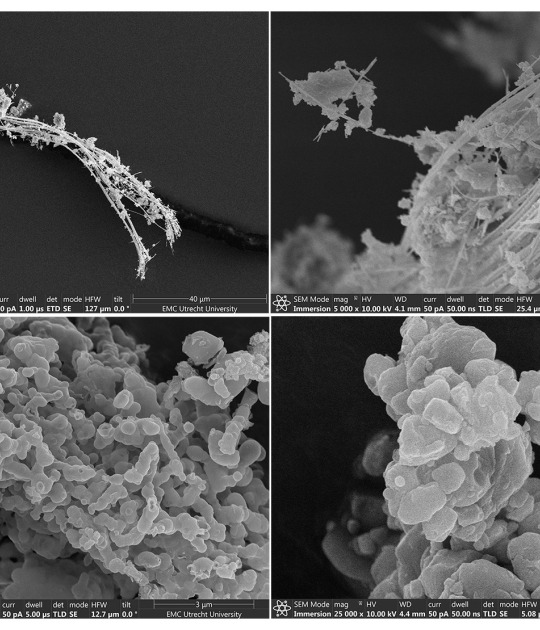

The greenhouses landscape of Koppert Cress, looks like something out of “Ad Astra”: silent spaces the length and breadth, an atmosphere monitored like operating theaters, plants stretching as far as the eye could see in gridded rows beneath red, green or white lights.

“Definitely stressful,” Koolhaas said, then added, “and fantastically beautiful.” Places likes these Koolhaas calls “post-human” buildings — whose boredom he finds “hypnotic” and “banality breathtaking” — represent, he says, a “new sublime.”

An expanding universe of data collection hubs, storage hangers and other digital-era behemoths that, like Koppert Cress, are reshaping the hinterlands. Designed by codes and algorithms, not human inspiration, industrial facilities on this scale, once upon a time, employed hundreds or thousands of workers. Now, like Koppert Cress, they’re staffed by two dozen. A new manifesto of course extremely frightening

“But it is also exhilarating.”