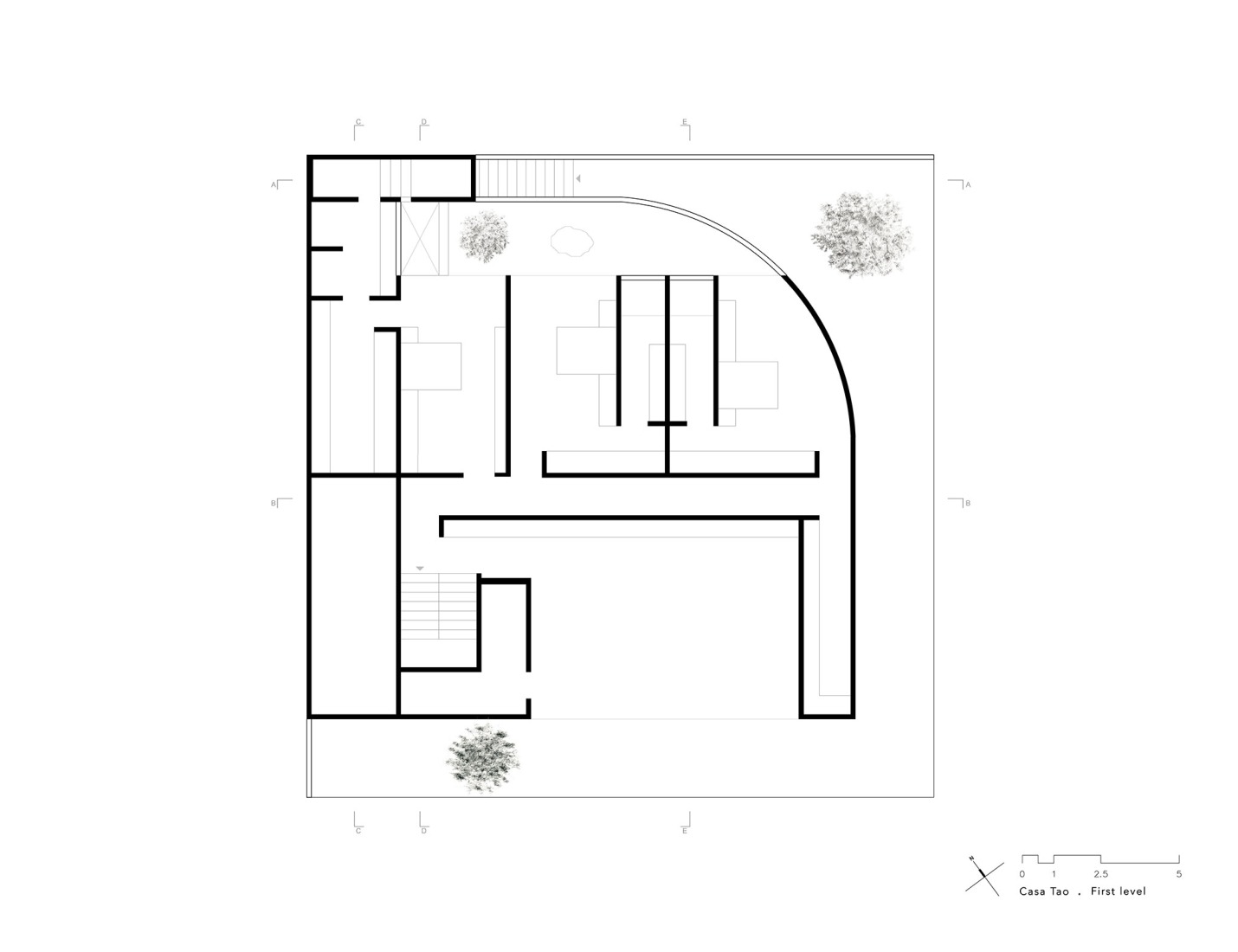

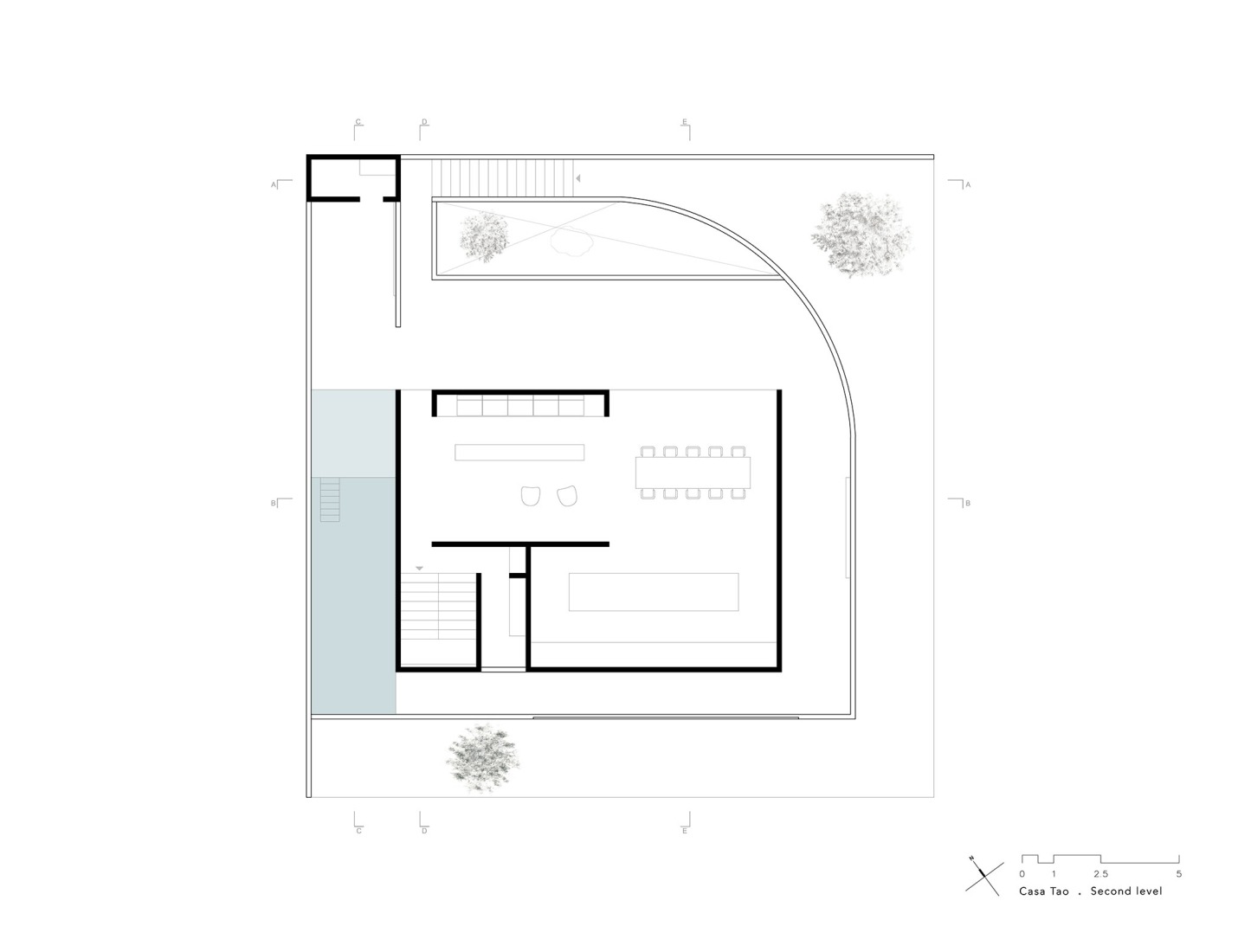

The design developed by HW Studio avoids large glazed surfaces and instead establishes diagonal relationships that allow the presence of the exterior to be intuited without direct exposure to the intense sunlight. The program is organized with the bedrooms, parking, and services on the ground floor, while above them a light double-height box rises, housing the social areas, open to the wind and the trees. Elevated patios function as terraces for contemplation, and the bedrooms are grouped around an interior courtyard that ensures silence, ventilation, and an intimate inward-facing world.

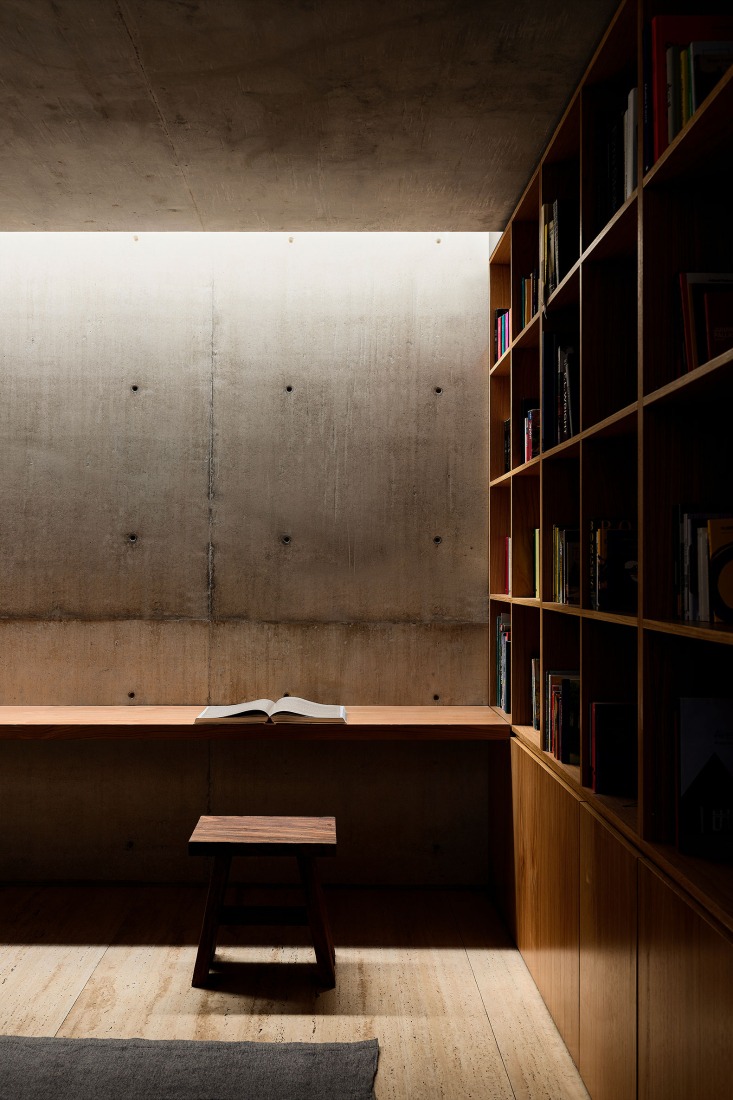

Materiality responds to a tactile and sensory intention. Concrete, heavy and honest, absorbs light with delicacy and acquires warmth through use and time. Whiteness stands out under the coastal sun and creates an environment where light does not reflect violently but instead settles gently, producing serene atmospheres in which shadow is refuge and life becomes contemplative.

Tao House by HW Studio. Photography by Tirso Domínguez.

Project description by HW Studio

Some houses are not designed—they are remembered. Casa Tao was not born from a technical drawing, but from the silent memory of those who inhabit it. It is a house that does not seek to respond to an image, but to a life. Or rather: to a way of living.

Gustavo grew up in a humble house made more of effort than of materials. The son of farmers and craft merchants—people with rough hands and generous eyes—who, though their studies were prematurely interrupted, managed to instill in him a desire to understand the world. He grew up in Puerto Vallarta, a place on the Pacific coast of Mexico, where sun and humidity define the rhythm of the days, and where shade is not an accident, but a precious asset—a true refuge. From the beginning, the house needed to translate that need for shelter, for seclusion, for coolness. The concept of shade was not understood here merely as a physical phenomenon, but as an emotional condition: a promise of calm, of breath, of silent protection against a clamorous world.

But it was Gustavo’s personality—as rich and complex as the place of his childhood—that deeply shaped the design. With uncommon curiosity, he is a man who has made self-taught knowledge his path. Philosophy, architecture, music, photography: I get the impression that little is foreign to him. His library, filled with special editions by Alberto Campo Baeza, Fan Ho, Tarkovsky… reveals an affection for formal clarity, for essential geometry, for quiet courtyards that converse with emptiness and light. Speaking with him is to immerse oneself in a view open to the world—deeply sensitive and at the same time precise.

His story with Cynthia, the second inhabitant, is also an essential part of this architecture. Together with their two daughters, Mila and Anto, they took their first trip abroad, to Japan. That journey left an indelible mark on their imagination: the aesthetics of emptiness, compositional cleanliness, and the stillness contained in every architectural gesture. They told us with a smile, “We’d like to feel as if we were living inside a Japanese museum.” But they did not mean the solemnity of the museum as an institution, but rather that type of space where time slows down, where light filters gently, where silence becomes tangible.

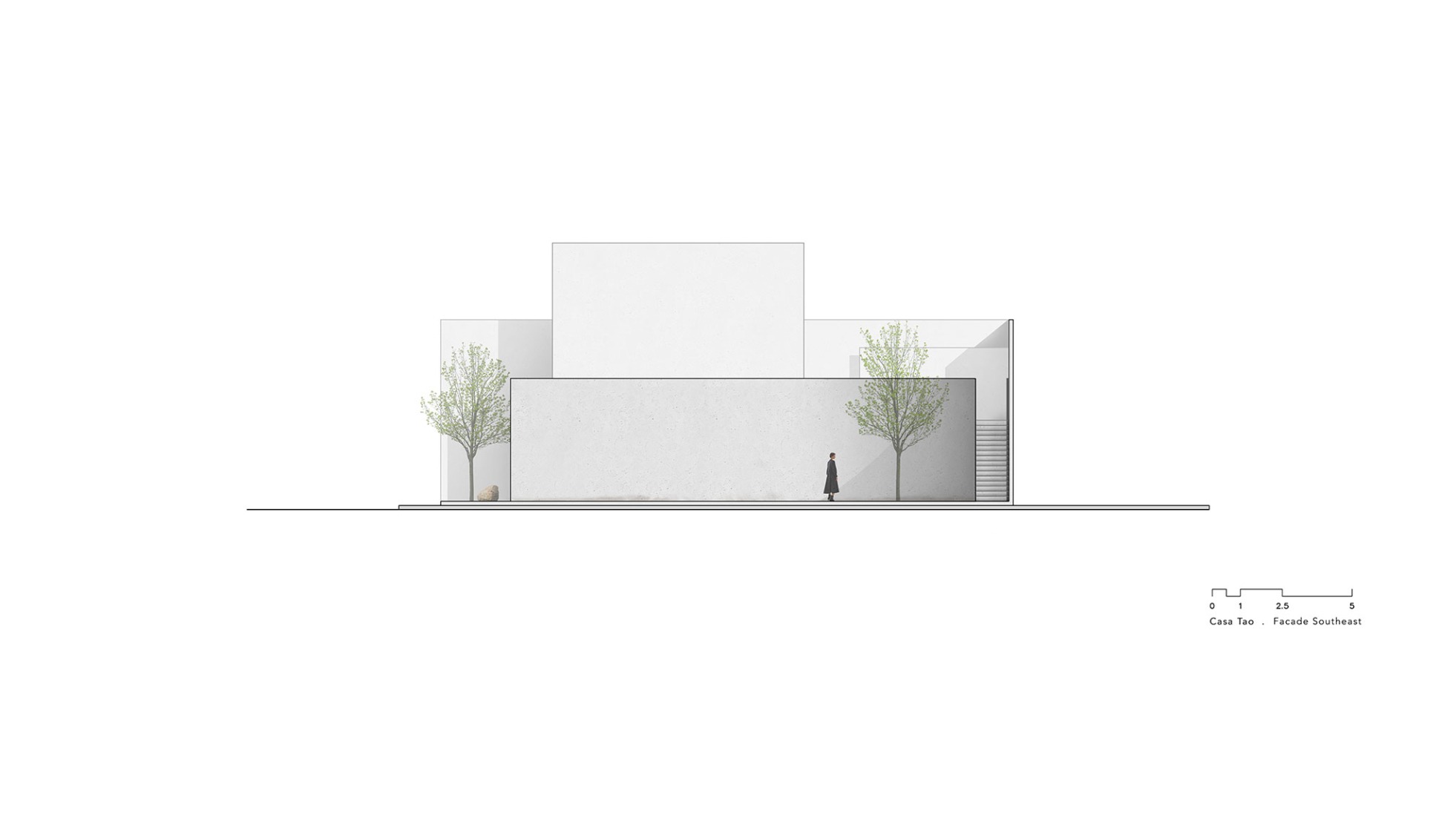

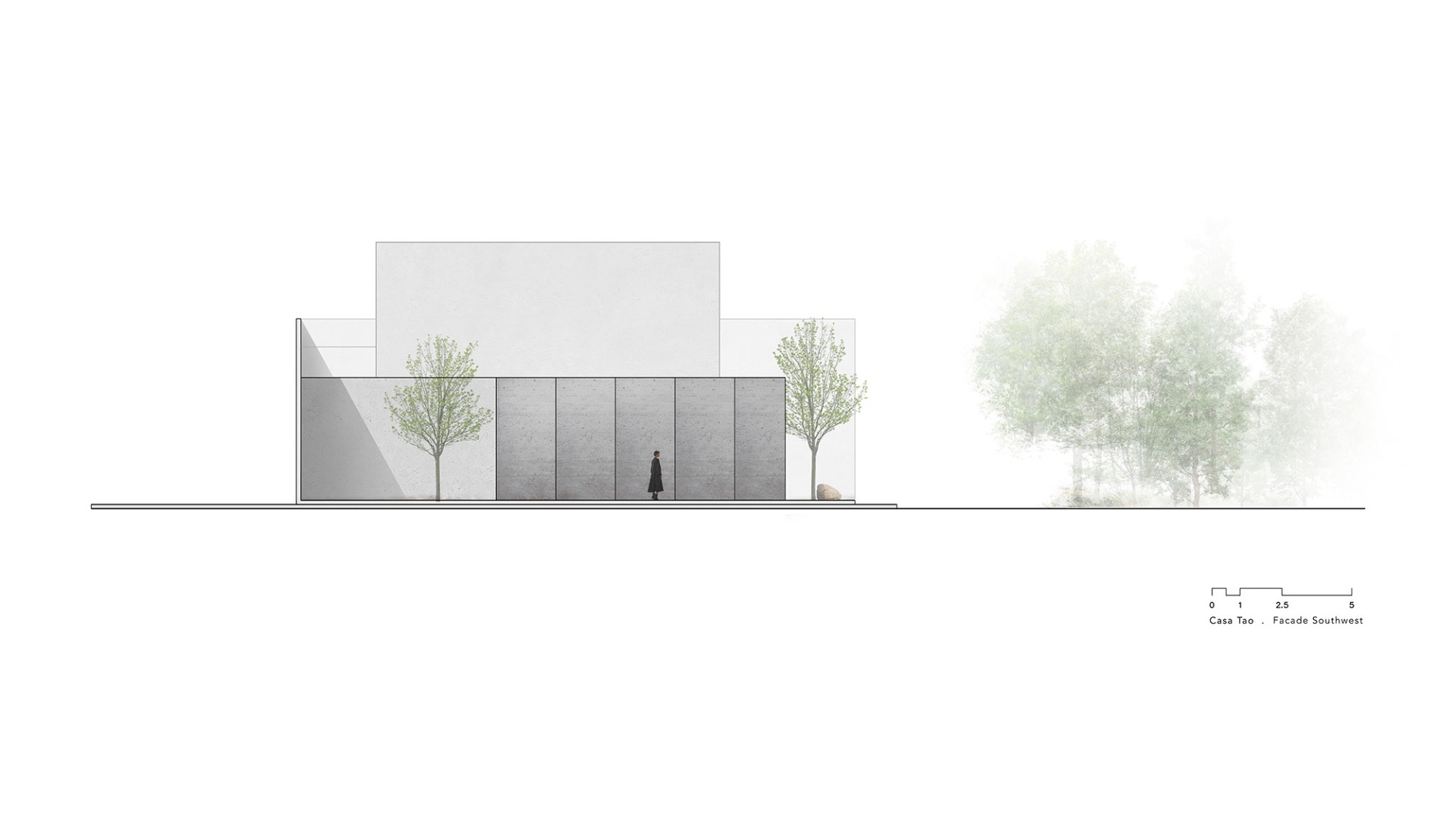

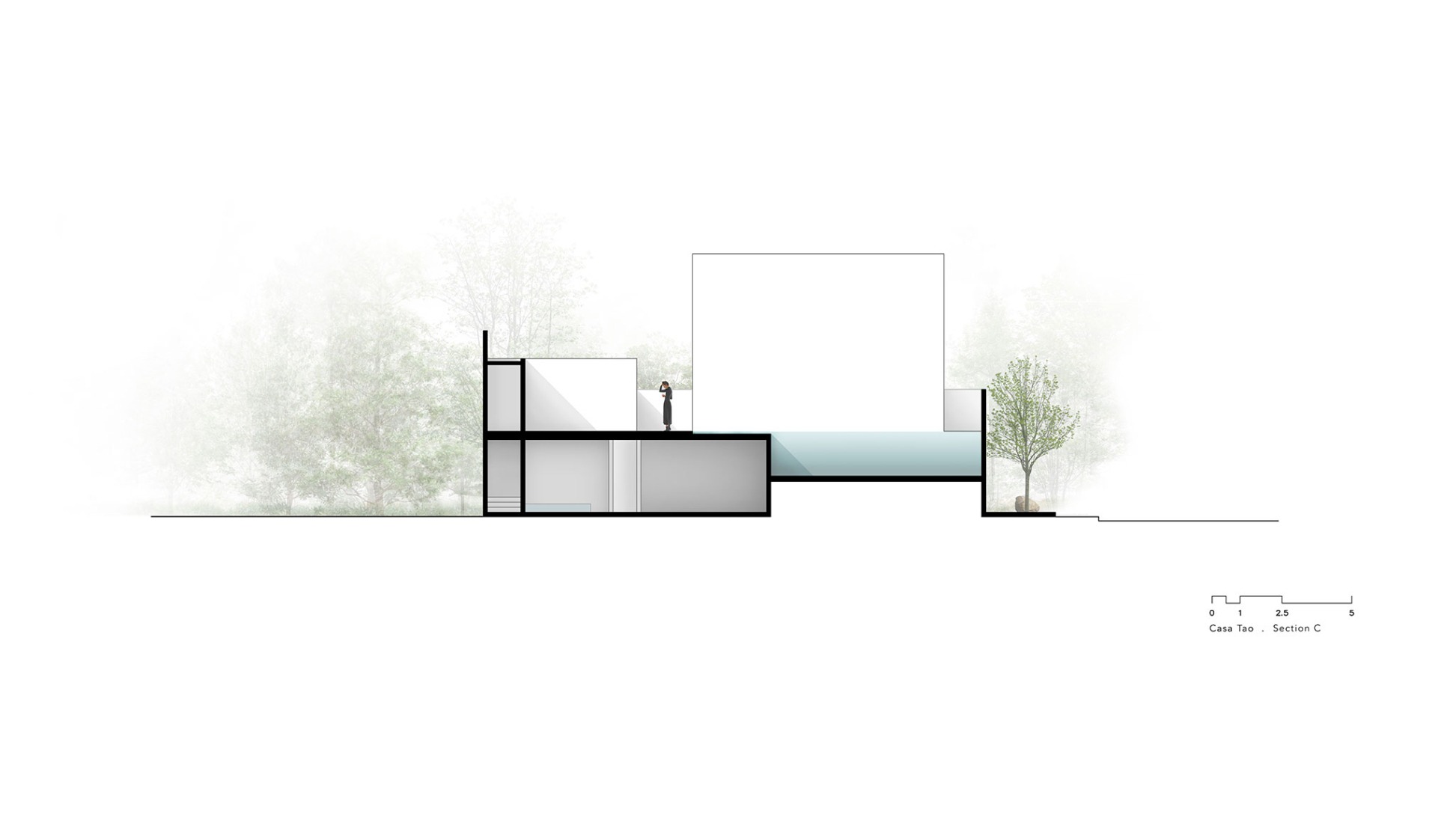

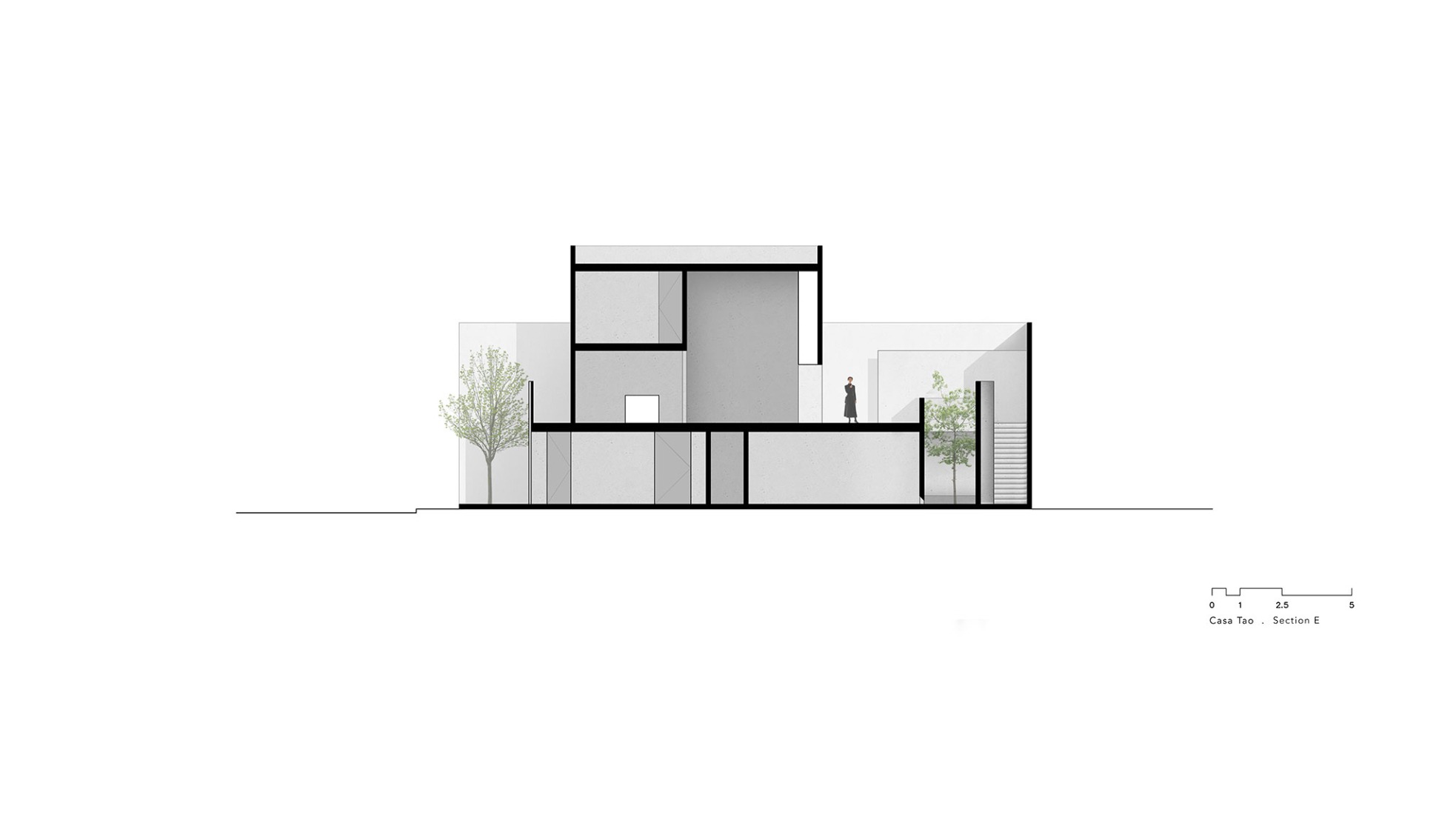

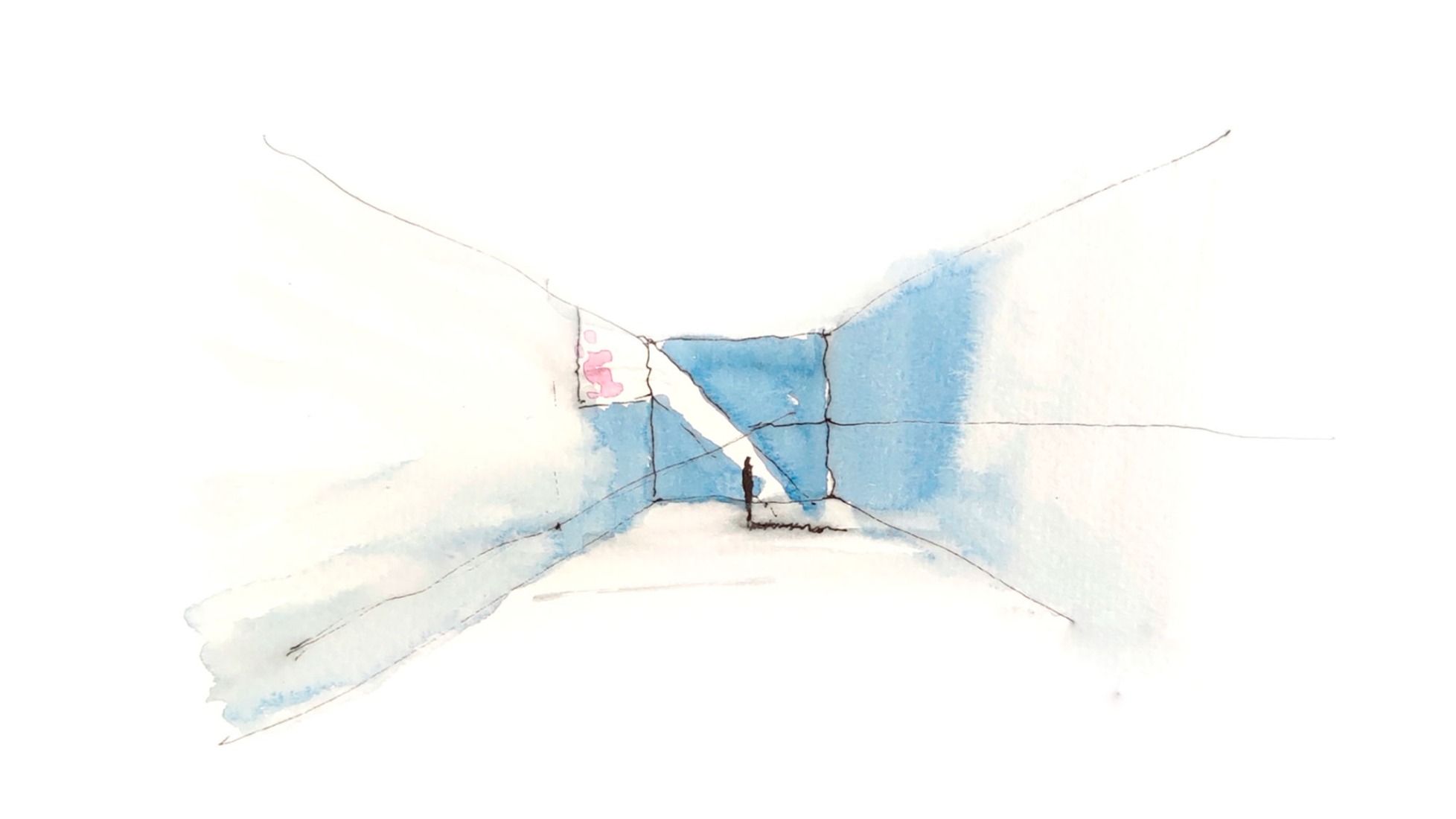

And that is what we tried to do. In a neighbourhood with no remarkable views, except for a tree-lined plaza that offered shade and breeze, we decided to orient the architecture toward that freshness. But we did not do so frontally. We avoided large glazed surfaces that might intensify the heat. Instead, we proposed an oblique, angled relationship that allows the presence of the plaza to be sensed without being fully exposed to the heavy sunlight. The act of dwelling is framed indirectly, as if the house were observing at a diagonal, modestly, letting only the wind and the fragrance of the not-so-distant sea pass through.

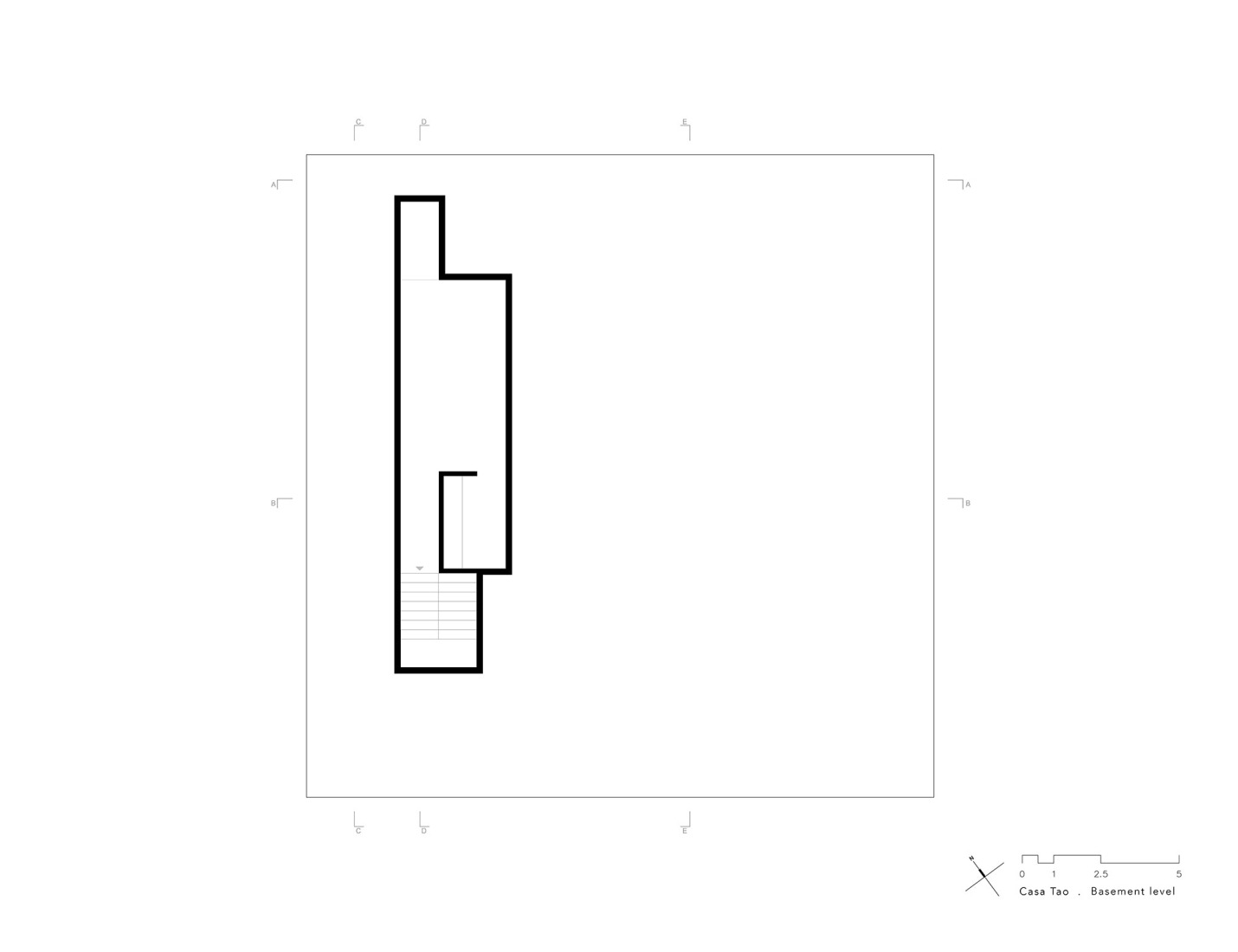

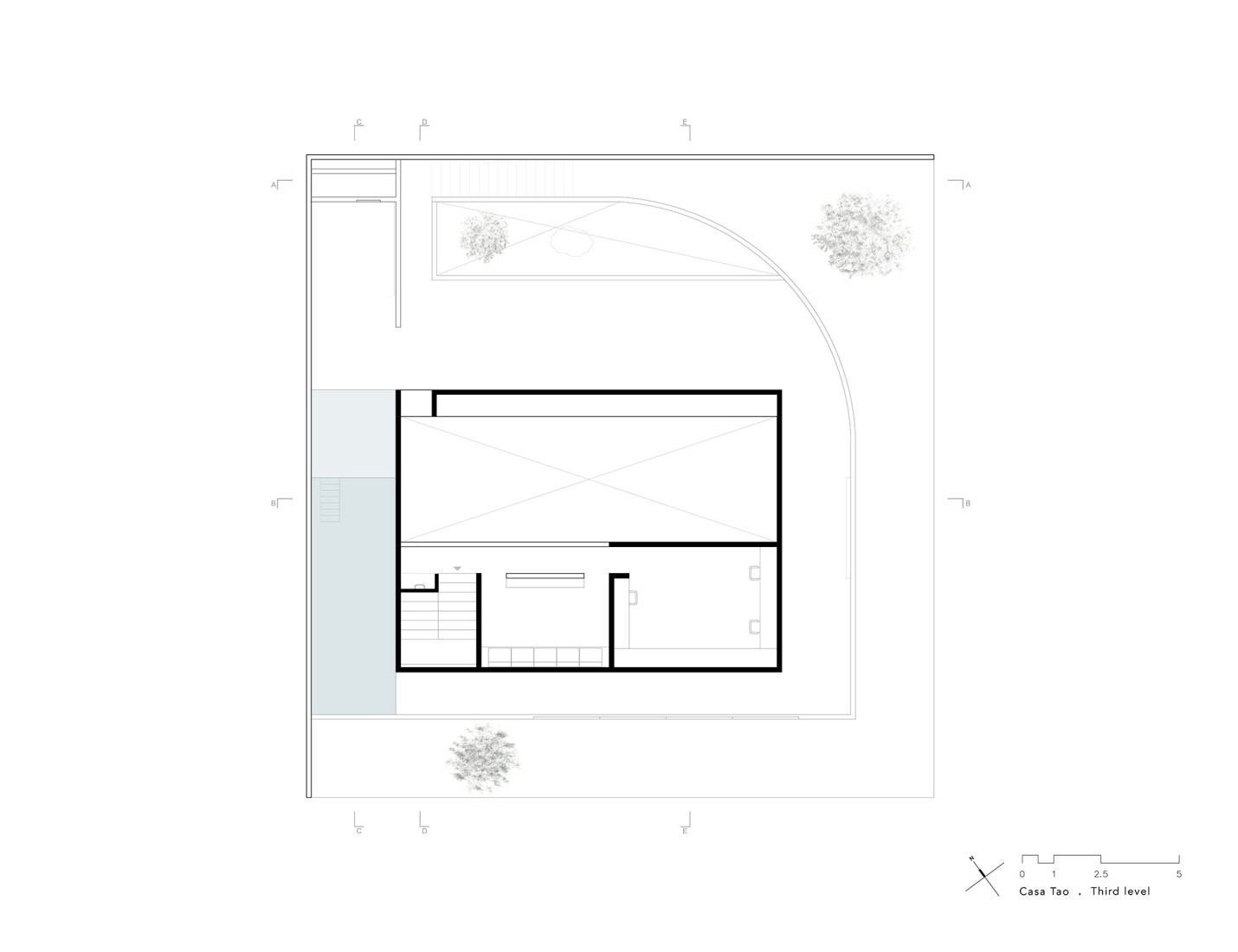

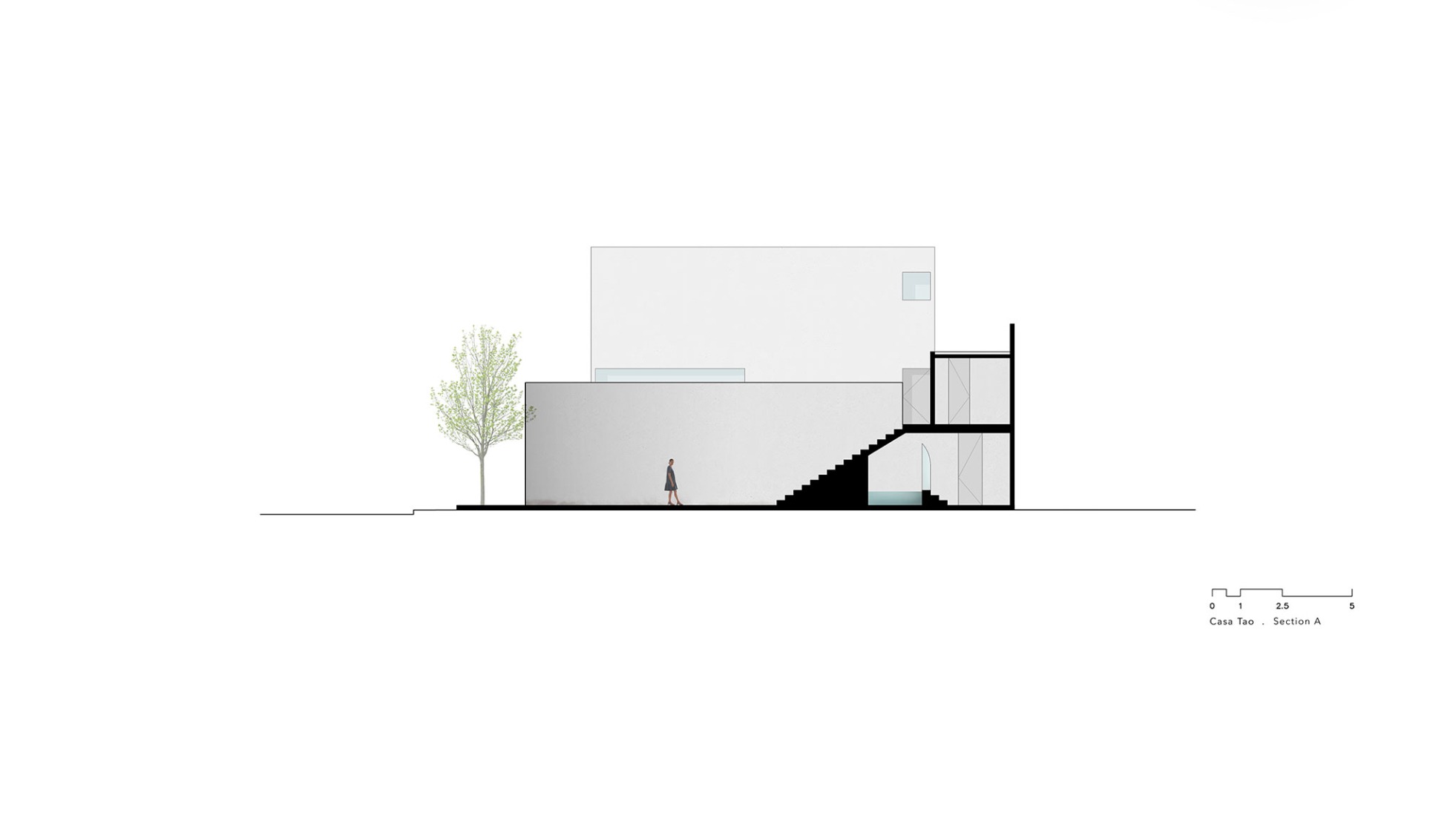

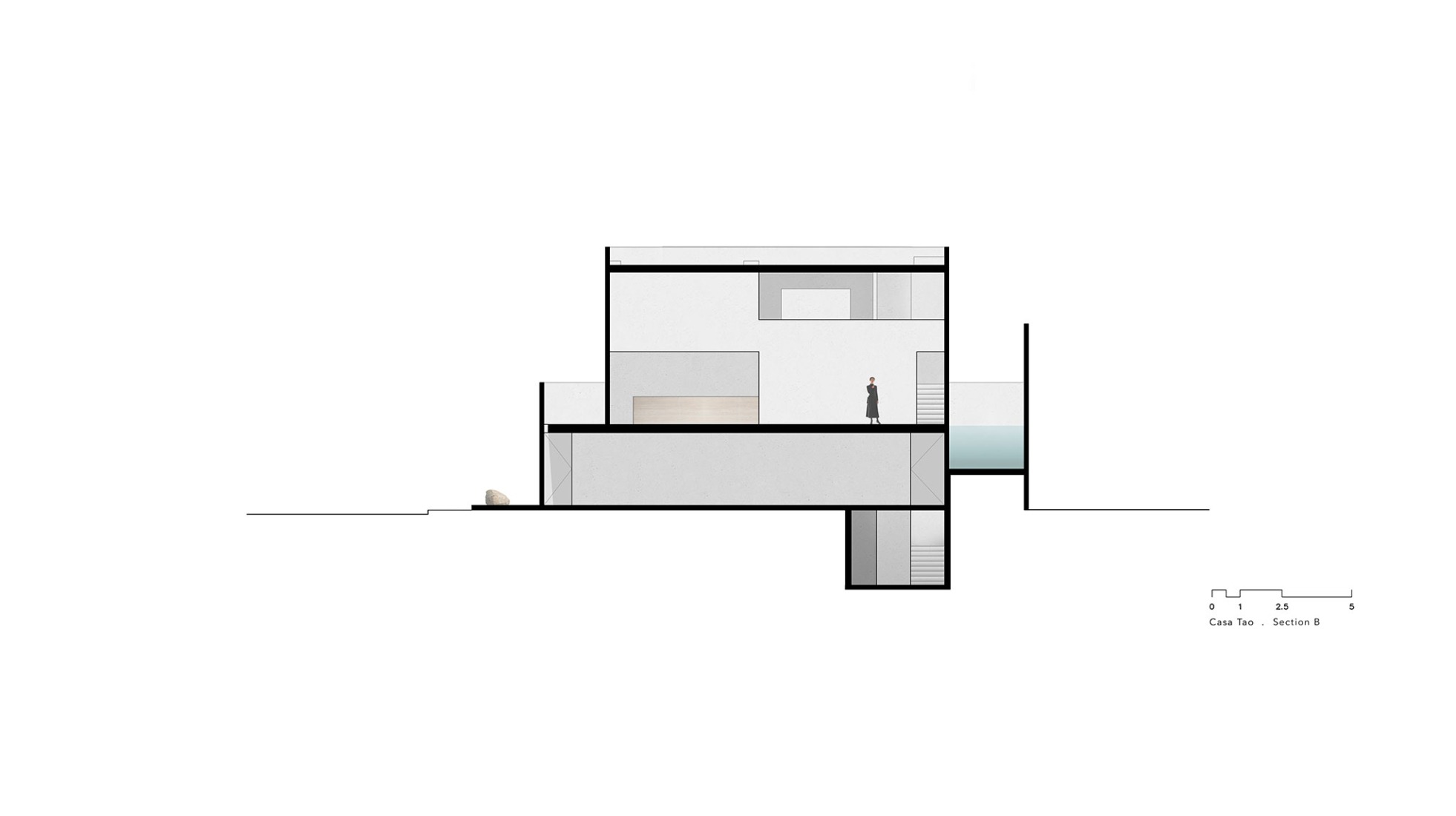

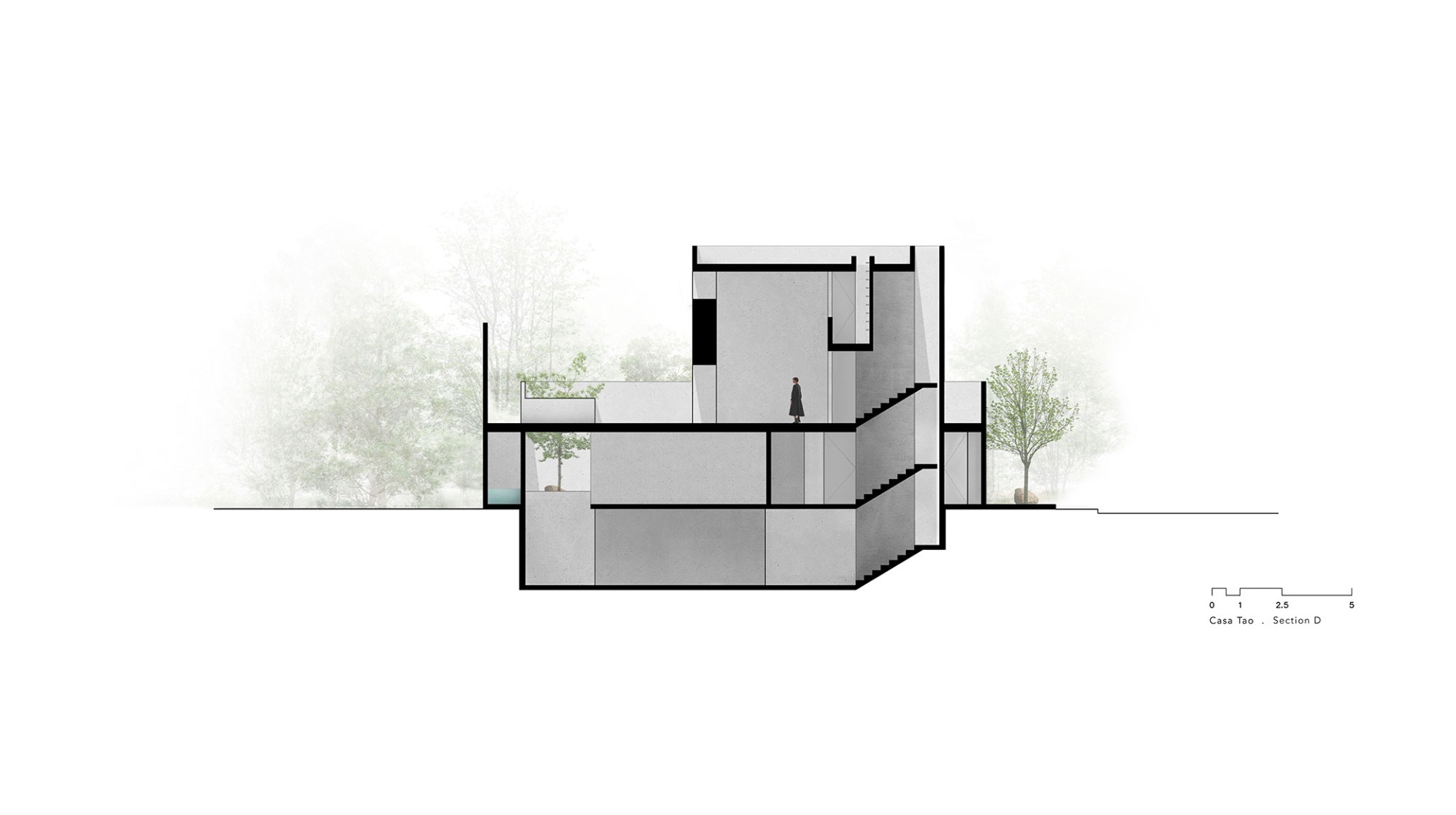

We placed the larger program—the bedrooms, garage, and service areas—at the base, and above it, we suspended a light, double-height box containing the social areas. This strategy allowed us to raise social life above street level, surround it with air, and open it toward the trees and the salty breeze that crosses the plaza. The elevated patios act as terraces for contemplation—small platforms from which to better breathe the scent of flowers and hear the murmur of wind among the treetops.

The bedrooms are organised around a patio, seeking silence and air. Here, intimacy is expressed through enclosure—not as confinement, but as an interior world. A curved wall receives the visitor gently, marking a welcoming threshold, while a tree greets you like a floral arrangement. The house does not look toward the neighbourhood; it turns inward, like someone seeking refuge. But it does not close itself off: it opens to the sky, the shade, the plaza. Everything is arranged so that living happens in a slower, fuller way—more open to the invisible.

The materiality was inevitably tactile and sensory. Whiteness dazzles under the coastal sun, while concrete—heavy, honest—absorbs the light with delicacy. It is a concrete that becomes warm through use and time. In this material, light does not bounce; it settles. Casa Tao is, ultimately, an architecture born of the desire to inhabit the world with greater attention. It is a house that withdraws discreetly and offers its spaces as atmospheres for contemplation and memory. In it, dwelling becomes a form of study, of pause, of gratitude. Every corner invites one to remain, not to pass through, and every shadow is a promise of well-being.

This deliberate search for shade—as refuge and poetic quality—brings us closer to a spatial understanding similar to that described by Junichiro Tanizaki in In Praise of Shadows. There, Tanizaki does not celebrate darkness as the absence of light, but as a subtler way of seeing. In his text, shadow is not an obstacle, but a veil that ennobles—a way of amplifying the depth of things, of allowing beauty to emerge slowly, with humility. So too with this house: it is not illuminated assertively, but lets the penumbra suggest; it allows light to filter in without violence, and each space becomes a nuanced, contained sensory experience in which time thickens and life grows quiet.