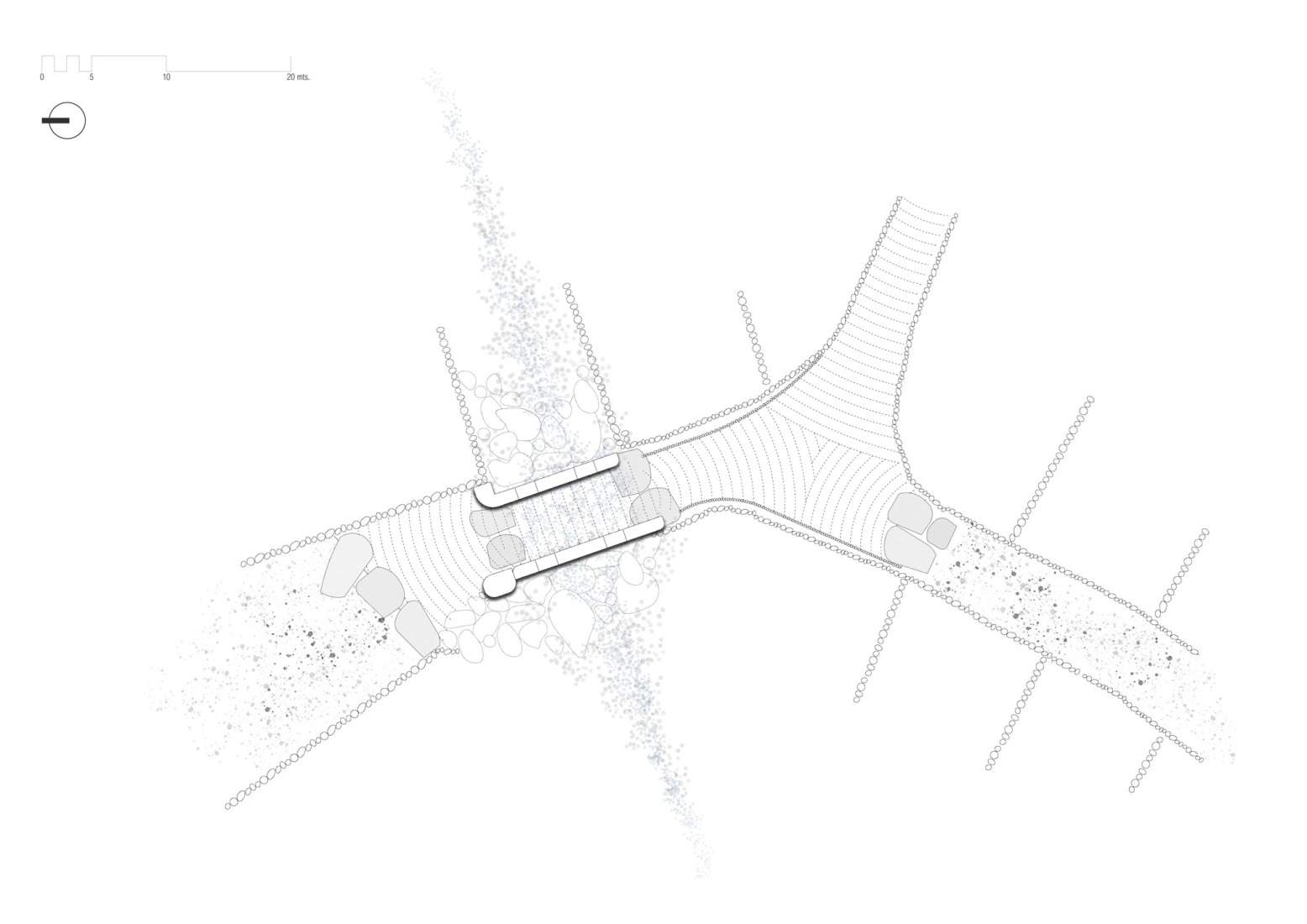

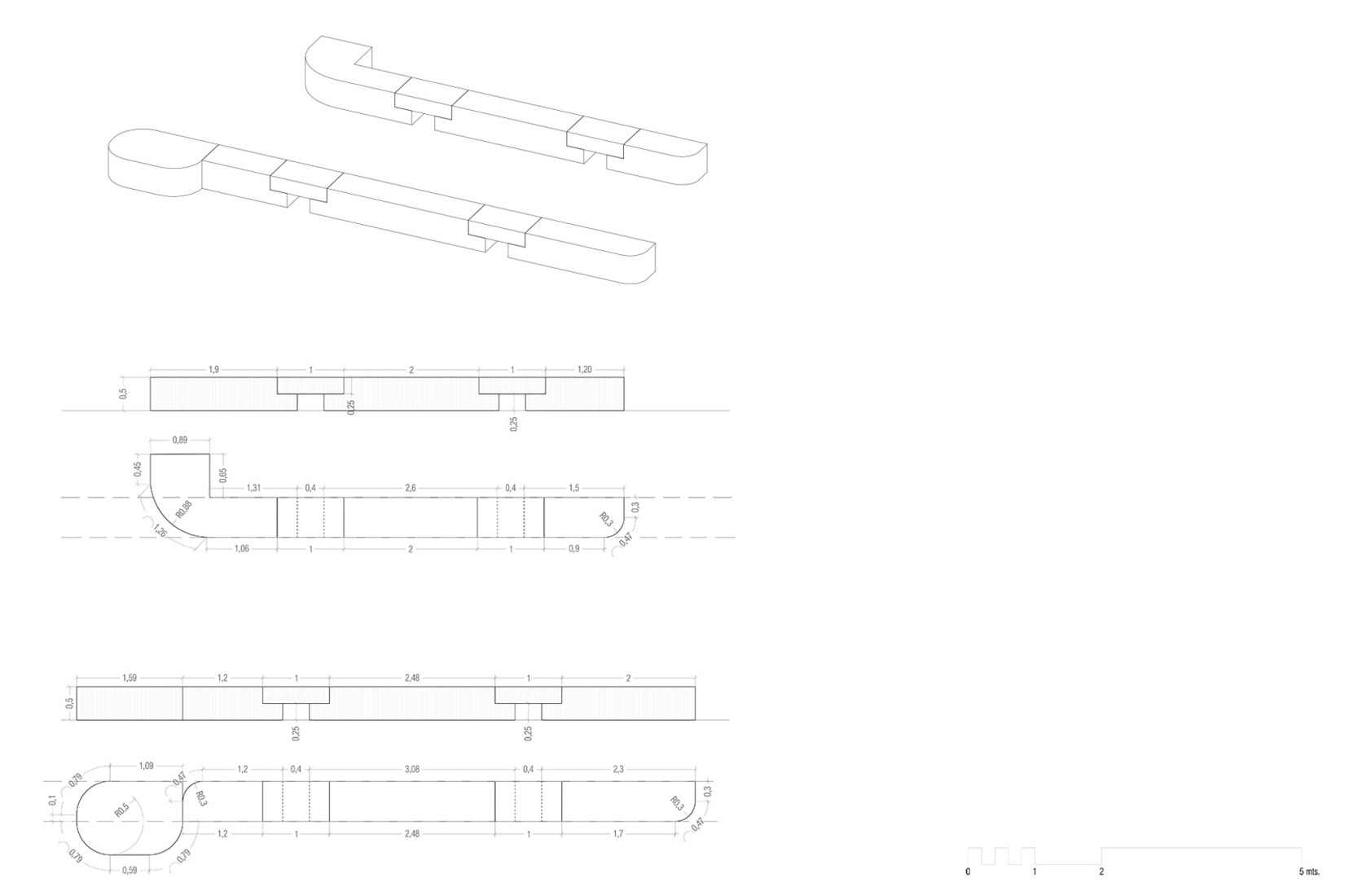

María Fandiño Iglesias designed a parapet over the river, made of granite stones placed and fitted together by hand. The site is strategically located in the shadow of the river and is the right size and shape for people to rest. It has large openings that allow rainwater to drain. The paving is stone in flood-prone areas, and each paving stone adapts to the shape of the path, respecting the slope and reflecting the flow of the adjacent river.

Water is collected and channeled using sand and pebbles native to the area, blurring the boundaries between the natural and constructed areas. The project creates an intermediate level between the stone bridge and the riverside vegetation. The carefully planned intervention pays special attention to the intersections between pavements and turns, mimicking the large granite casqueiros and traditional access laxes to the plots.

The result is a constant dialogue between ancestral and contemporary techniques, reviving the colorful landscape, along with the sound of river water on the stones, before converging into the sea.

Conditioning of the Villar River Bridge by María Fandiño Iglesias. Photography by Héctor Santos-Díez.

Description of project by María Fandiño Iglesias

Guarded by Sierra da Groba Mountain, the Villar River descends along its western slope until the Atlantic Ocean. On its way, it passes through a stony landscape ranging from large mountain rock formations to small granite boulders.

The stream flows beneath the PO-552 road and the “Estrada Vella” — the current route of the Camino de Santiago along the coast — an old path that runs parallel to the horizon across a heavily anthropized plain. The dry-stone walls that mark the boundaries of the plots protect the crops from marine salinity and, at the same time, form paths over large laxes (stone slabs), where the ruts left by old carts are still visible.

The construction of the PO-552 in the 1990s interrupted the natural runoff from the mountain, channeling some flows and blocking the smaller ones. With today’s rainfall patterns, this leads to flooding, path degradation, and erosion that threaten the dry-stone walls bordering the “Estrada Vella,” endangering the local heritage: its landscape.

The project seeks to resolve this crossing by improving drainage, topography, and public safety, while also proposing a rest area for pilgrims. It is conceived using a single material: stone.

The parapet over the Villar River is built with large granite pieces, carefully fitted together by hand. Its width allows for resting without the need for furniture, in the shade of the river and its riparian vegetation. The gaps between stones ensure proper drainage during the rainy season and allow for nighttime lighting.

The paving, made of stone only in flood-prone areas, follows the logic of water — the project's driving force. Its fluid geometry adapts to changes in slope and emphasizes the connection between river and sea. The cobbled surface forms a veil that dissolves at the edges into the lateral caz (drainage channel).

The caz is built with sand and river pebbles found during excavation, creating a subtle transition between built and natural elements. At junctions and turns, large granite casqueiros — trimmed offcuts from the quarry — recall the traditional laxes that provide access to the plots.

The result moves between the technical precision of the material and the spontaneity of ancient masonry walls. It is a dialogue between new uses and ancestral land, inviting passersby to sit and listen to the clear waters of the Sierra da Groba flowing over the stones before reaching the sea.