Jan Kaplicky and Future Systems

Jan Kaplický (1937-2009) grew up in a family of intellectuals and artists in 1950s Prague. He studied in the Academy of Applied Arts there before embarking on his first minor architecture projects. He was particularly interested in the technical aspect of architecture and was influenced not only by the architecture of the Czech Functionalists, but also by American aircraft design. When, in August 1968, the political and social liberalization introduced by Alexander Dubček – known as the Prague Spring – was brought to an abrupt end by Soviet troops, Kaplický left the country, along with so many others.

Kaplický arrived in Swinging London as an émigré in fall 1968 and worked there until 1983, both as a freelance architect and for various architecture firms. He was, for instance, involved in planning Piano + Rogers’ Centre Pompidou (1971–77) in Paris and Foster Associates’ Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank (1979–86) in Hong Kong.

In 1979, together with another architect, David Nixon, Kaplický established his own architecture firm, Future Systems. Many of their designs were reminiscent of constructions relating to space technology and were located in uninhabited spots of the world. Future Systems attracted the attention of both the trade press and Peter Cook (Archigram), resulting in exhibitions in London, Paris, Chicago and Frankfurt/Main in the 1980s.

Future Systems underwent a change of direction when Amanda Levete came on board in 1989. David Nixon had left the company two years earlier. Now, their new motto became more buildings and less theory. Major competitions were to follow; however the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris and the New Acropolis Museum in Athens were two contracts that Future Systems did not win.

The Selfridges department store is probably Future Systems’ best-known building and it has been a landmark of downtown Birmingham, England since 2003. One of Kaplický’s last projects was a new building for the Czech National Library. After he had won the competition his amorphous blob design became the object of a fierce debate in Czech society. The library remains a blueprint and the site a wasteland above the Vltava River…

Archigram

1961, the year when Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space and the Berlin Wall was built, was also the year when the Archigram group was established. In a social climate torn between progressive optimism and concerns about a nuclear war, a set of young architects emerged – Peter Cook, Warren Chalk, Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton, Michael Webb and David Greene – and completely changed the face of the British architecture scene. They had all met at a London-based construction company, Taylor Woodrow Construction.

With Archigram the focus was on publishing as well as designing from the very outset. The name of their magazine, Archigram, was formed by amalgamating architecture and telegram. The magazine became more substantial from issue to issue, developing into a mouthpiece for 1960s architecture.

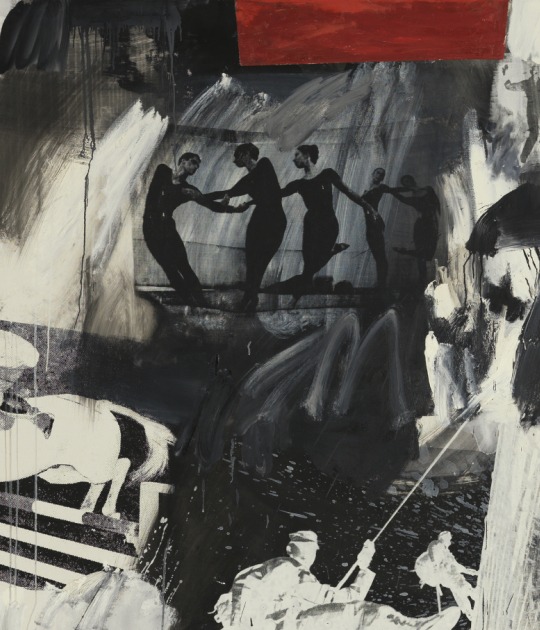

Archigram drew on the music, art and fashion of its times not only for inspiration, but also as a pool of materials for its utopian urban architecture collages. Its members used the principles of Pop Art to disseminate their utopias, with their architecture being guided by their common interest in new technologies, social change and spectacular shapes. Their urban projects such as City Interchange or Plug-in City clearly reference Yona Friedman’s mega-structures and the tower cities of the Japanese Metabolists. Archigram broke apart in 1974. Its members went their separate ways, but remained in close contact.

1980s Frankfurt was also associated with Archigram and Peter Cook. In 1984, Cook became Professor of Architecture at the Städelschule; in 1992 he designed its new cafeteria. In the years following the establishment of the DAM its director Heinrich Klotz acquired work by Archigram for the museum’s collection. And in 1986 a major exhibition at DAM, Vision der Moderne, featured, alongside work by Coop Himmelb(l)au, OMA and Future Systems, a large number of Archigram’s drawings and collages.