Inspired by John Ruskin's ideas on the restoration of historic buildings, the architects have opted for an aesthetic in which factors such as time and decay are part of a romantic reading of a building produced in a complicated historical process, providing a modest and sensitive approach.

Wintercircus Mahy by Atelier Kempe Thill + aNNo Architecten. Photograph by Architektur-Fotografie Ulrich Schwarz.

Wintercircus Mahy by Atelier Kempe Thill + aNNo Architecten. Photograph by Architektur-Fotografie Ulrich Schwarz.

Description of project by Atelier Kempe Thill and aNNo Architecten

Invisible modernism

Ghislain Mahy's makeover of the circus building complex is impressive in many respects. He first made the radical decision to remove the wooden grandstand inside, with stucco ornamentation and a false ceiling, and reduce the main round building to its bare concrete framework. As a result, he unveiled a massive atrium, an empty space that would serve as the focal point of his activities. Afterwards, step by step, he added ramps and new extensions inside and outside the main volume, basically to make all of the floors accessible for his cars.

Due to the complicated setting in the city center and the rather complex topography and connections to the existing city, a real systematic and clear approach was impossible. Instead, the entire complex became a kind of Merzbau, at first glance a messy and simultaneously phantasmic collage, evoking the works of German Dada Artist Kurt Schwitters in the 1920s. Mahy made simple extensions where possible, in such a way that it always resulted in unexpected beauty. Indeed, he didn’t pay much attention to minimum heights or the curve radius or the steepness of ramps. Nor did he take legal matters, such as building permits, very seriously either. In fact, some of his projects were only regularized after having been completed. Instead, he concentrated all his efforts on creating sensible connections that would best serve all of the activities in the building. He used the spaces in a situationist manner that befitted them, creating a rich variety of views and light situations, lovely small booths and counters, and surprising and elegant details in the windows, plinths and concrete works. Although not a professional architect, he still seems to have been a talented designer and a consistent modernist in heart. All of the transformations, extensions, spaces, and details he added to the building show an enormous love for building in an elegant, modernist way, which – together with the enormous atrium – results in a nearly breathtaking experience.

His anarchistic way of building extensions led to crazy situations, such as borders with neighboring buildings that are different in the basement than in the upper floors or the fact that parts of the building reach under the public domain of the street. He solved substantial technical problems, such as the danger that the entire complex would start to slide into the water of the Muinkschelde, by fixing the whole complex with a gigantic concrete pole at a strategically well-chosen and hidden place.Some of the spaces also remained unused by Mahy, especially the former stables for the circus animals in the lower floors. Interestingly, even after the current renovation – 80 years after the last animals had left – the smell of animal still pervades the space.

Mahy’s entire operation seems to mirror the Flemish mentality: being modern goes hand in hand, without there being any conflict whatsoever, with a penchant for the small scale. This seems to originate from an age-old spirit of craftsmanship and a nearly fetishistic love for detail. And all of this takes place in a location completely closed off from the city, hidden in a block. Those entering the old circus building are treated to an overwhelming spatial surprise when confronted by its unexpected monumental scale.

Wintercircus Mahy by Atelier Kempe Thill + aNNo Architecten. Photograph by Architektur-Fotografie Ulrich Schwarz.

A new life

In 2000, the car collection was moved to other locations and the building was abandoned. As a result, it fell into disuse and developed several problems, such as leaks in the roofs and façades, animals entering the building or intrusions by youngsters. Commissioned by the city of Ghent, the building was bought by the urban development company sogent in 2005 with the intention of renovating it while respecting its rich heritage. A competition was held by sogent to find an architect to transform the project and prepare it for a new life, which was won by Atelier Kempe Thill and aNNo architects in 2012. The intended program was a rock music hall for 500 spectators, a library for blind people, the Flemish archive for media VIAA, and the IT firm icubes. The building doesn’t have actual monumental status, but it is part of the protected streetscape of the urban environment. Still, the transformation of the interior needed to be discussed and agreed upon with the monument protection committee.

Façades and materials

The outer façades inside the block are all treated with thermal insulation on plaster and painted in light grey. The elegant steel window frames are black. The window partition follows the pattern of the old partitions. These façades don’t necessarily act as the “face” of the buildings but are hidden in the back and meant to function more from the inside-out than the other way around.

The former showroom on Lammerstraat is one of the few real front façades and has been restored according to the original setup and all its refined details, especially the window frames. The entrance on Sint-Pietersnieuwstraat is closed with a transparent gate of fine steel bars. The authentic brick façade towards Platteberg has been retained, and the windows there also resemble the originals. The building’s entrance is on Platteberg and has as its roof the concrete vault.

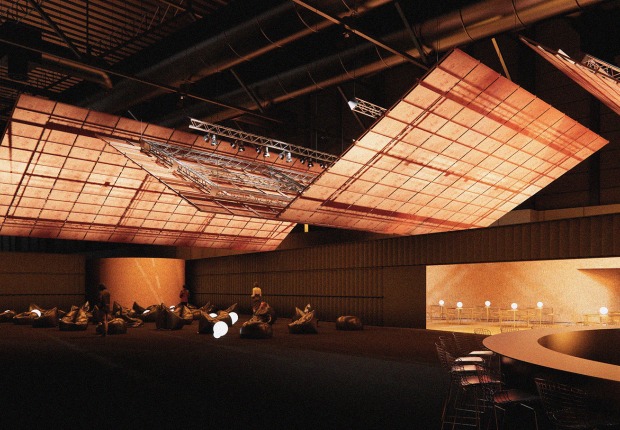

The façade in the huge atrium space – which is actually the most important façade of the entire complex – closely adheres to the original in its openness and expressiveness. Thin black steel frames were used here as well for the windows in combination with the rawness of the brick walls and concrete beams and the patina of the partly fallen off stucco.

For the Atelier Kempe Thill + aNNo design team, the Wintercircus project is a good example of how to use a consistent approach in restoring a historic monument. In a situationist design, the approach is mainly about modesty and sensitivity, about protecting the great spatial and tacit qualities of the existing building and putting them to a fitting new use. The result is not so much a “polished” project as a method of preservation, where factors such as time and decay are part of a romantic reading of a building produced in a complicated historic process. In that way, this curated decay approach adheres to John Ruskin’s ideas of restoring historic buildings.

The Wintercircus’s rough nature dovetails with the rising contemporary taste for raw and unfinished places that’s especially popular in subcultures. This tendency may be seen as a subconscious desire to create an escape from ongoing domestication, the domination of the digital, and a flawlessly planned and tidy environment, and instead to resurrect and to celebrate the wild, the tactile, and the spontaneous.