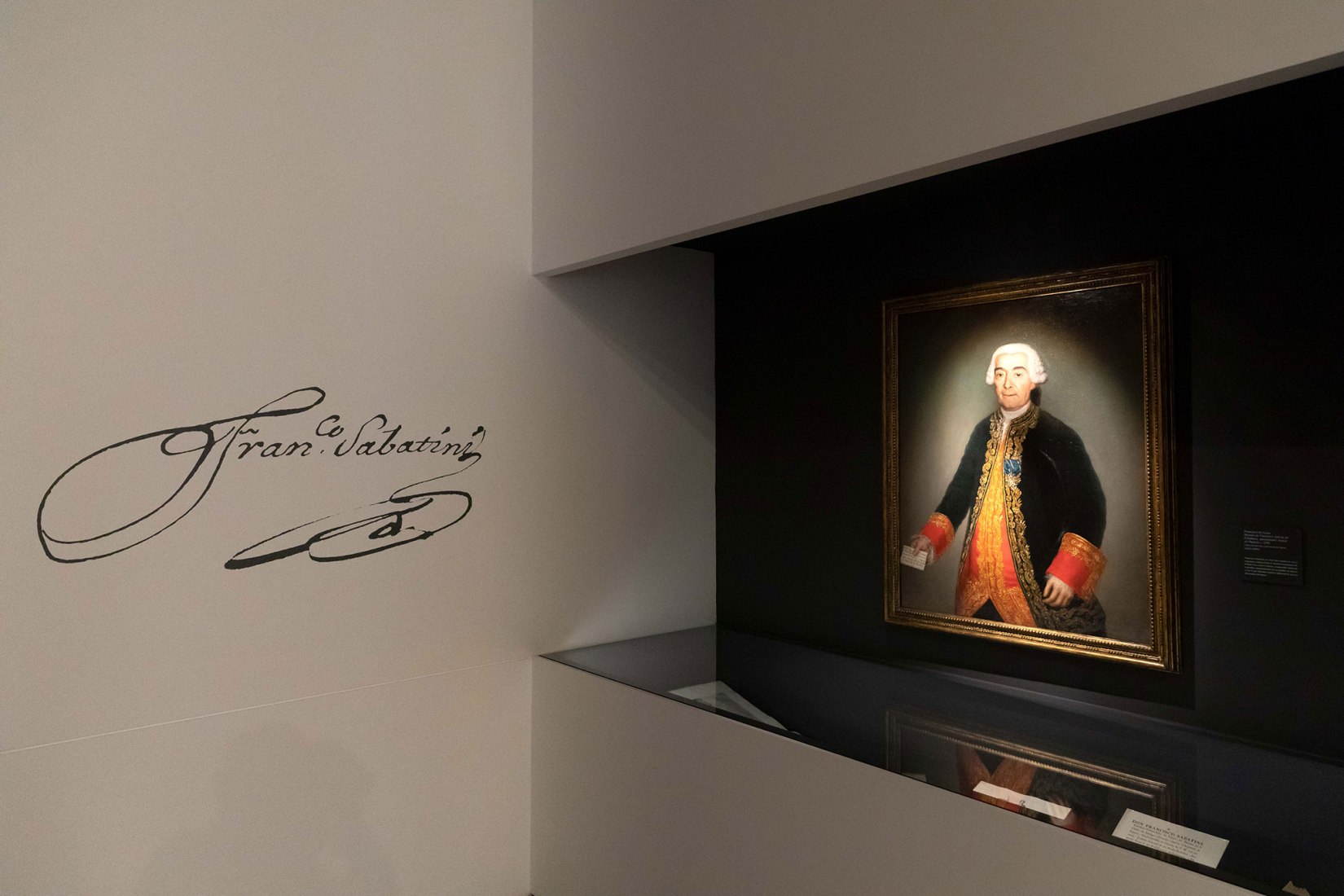

The life and work of the Sabatini are exhibited through the analysis of more than a hundred historical pieces, among which are the best plans and drawings of the architect from the main public and private, national and international collections. You can also see sculptural and pictorial works of art, including oil paintings by Francisco de Goya and Salvador Maella.

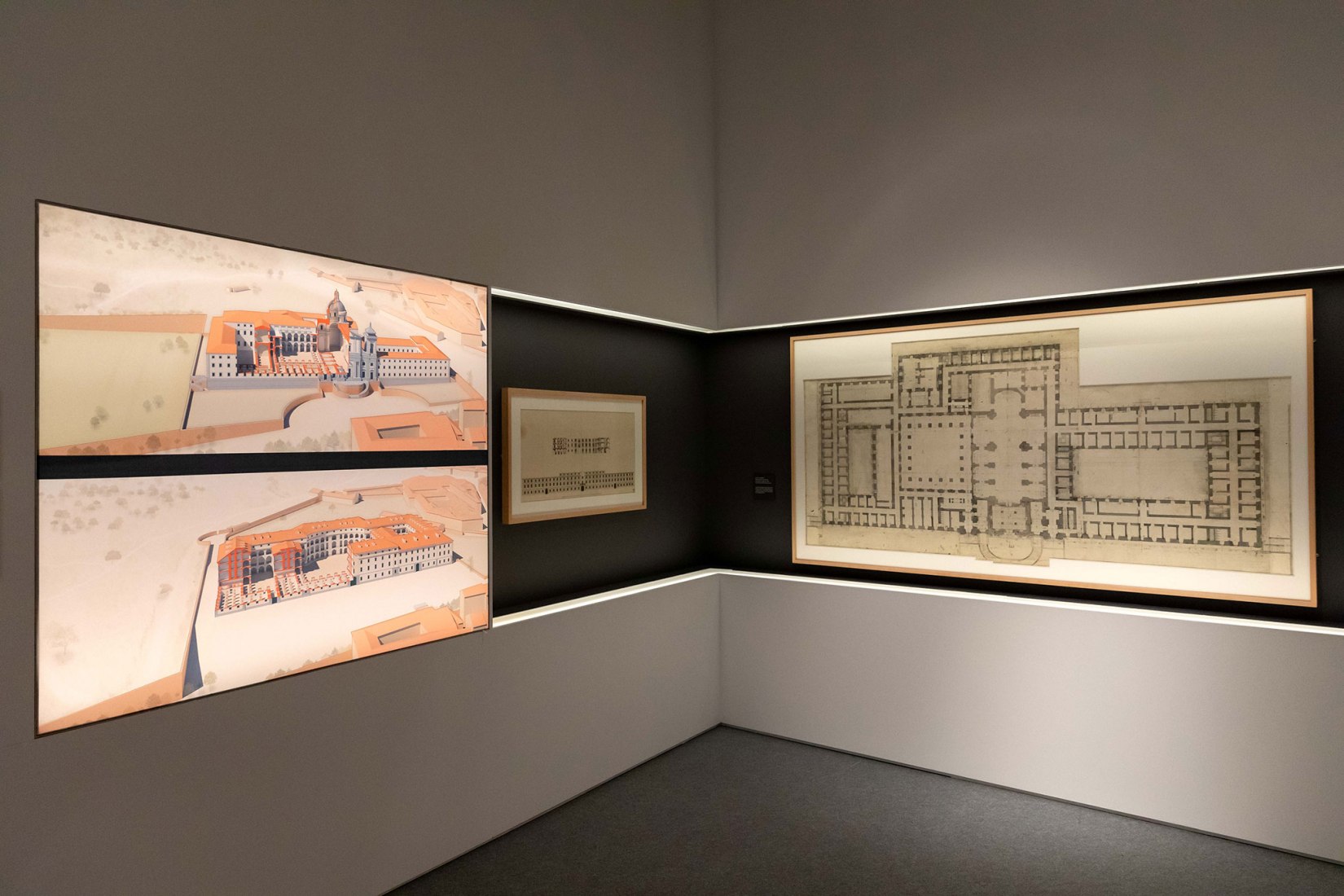

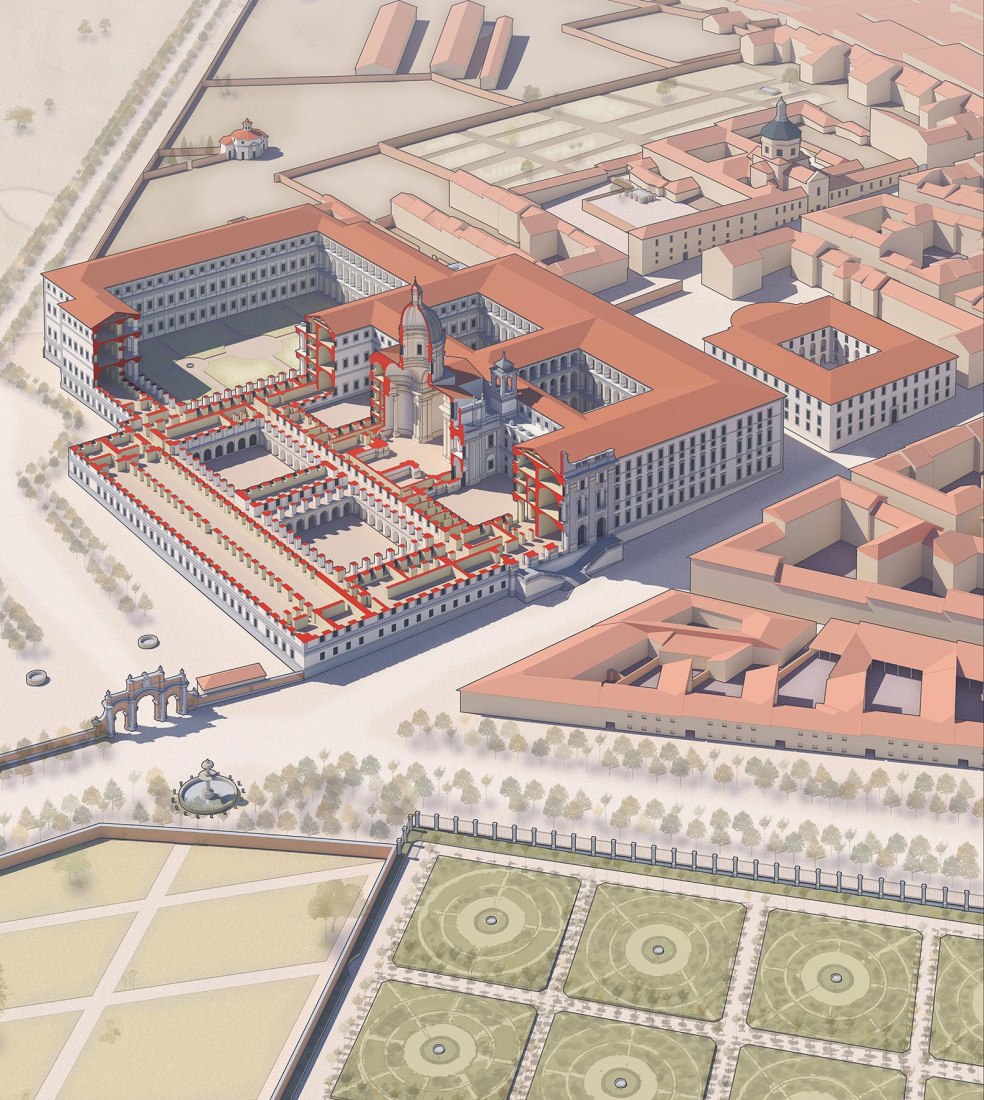

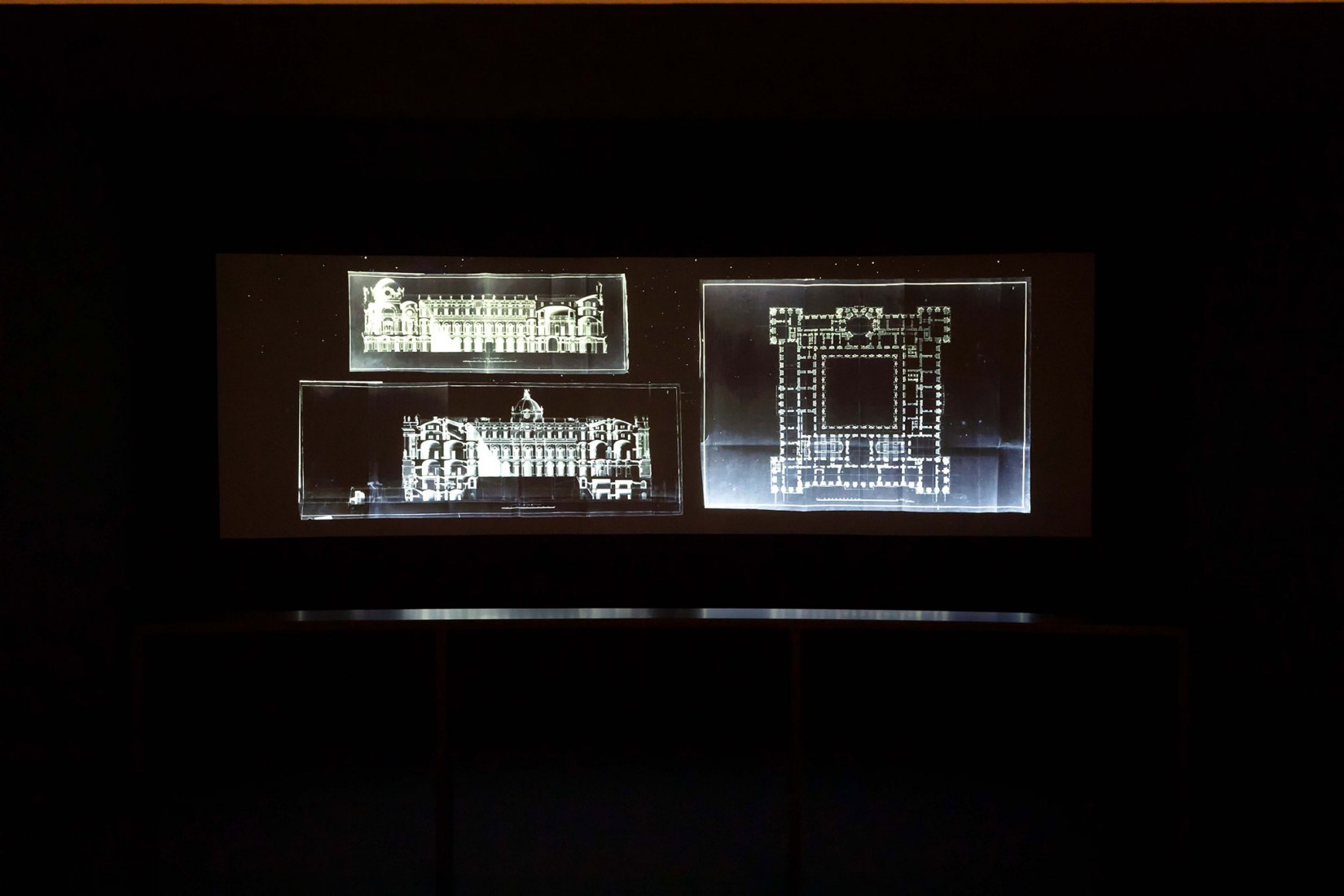

The exhibition facilitates the approach through a graphic narration of great technical quality and an innovative audiovisual production. The city that the Palermitano designed is exhibited before visitors through a graphic reconstruction in three dimensions that accompanies and completes the historical analysis of the transformation of the capital.

Architecture and power

Francisco Sabatini was an architect and royal engineer in the service of Carlos III and Carlos IV between the years 1760 and 1797. He is responsible for such emblematic works in Madrid as the reform of the Royal Palace, the Customs House, the Godoy Palace, the Basilica San Francisco el Grande or the Puerta del Real Jardín Botánico. His career of more than three decades at the service of the Spanish monarchy not only transformed the architecture of the royal sites, but also the morphology of the capital.

Madrid was in 1760 the capital of a vast transatlantic empire. Carlos III, who for more than 25 years had been sovereign of the Two Sicilies (1734-1759), knew what it was to rule a metropolis. The monarch had transformed Naples, the third most populous city on the continent after London and Paris, into a true European capital. When in 1759 he arrived in Madrid, he proposed to use the same architectural culture that he had tried in Italy and for this reason he decided to claim Sabatini, of whom he knew his efficiency and solvency.

The exhibition explains the relationship between architecture and monarchy, space and power, addressing not only the most important projects carried out by Sabatini for the city of Madrid, but also the model of State, nation and society that Carlos III tried to implement with the transformation of his capital.

La exposición se articula en torno a las siguientes unidades museográficas:

1.- Construir y gobernar: las artes al servicio del poder

En la tarea de construir una capital intervienen, hoy como ayer, muchas manos. En el siglo XVIII, si bien fueron los soberanos los que tuvieron la última palabra, otros importantes agentes políticos participaron de manera crucial en su gobierno y, en consecuencia, diseño y arquitectura. Entre ellos destacan los secretarios de Estado y del Despacho que, como Esquilache, Grimaldi o Floridablanca, estuvieron detrás de importantísimas iniciativas urbanas. El espacio, entendido como herramienta de gobierno, se convirtió de este modo en un asunto de Estado durante el reinado de Carlos III.

Sabatini comprendió rápidamente este axioma y desde su llegada a Madrid en 1760 acomodó sus diseños y proyectos a las necesidades y valores políticos demandados por los representantes de la monarquía y el Estado. Para ello, Sabatini no solo acudió a su experiencia en Roma y Nápoles, sino también al conocimiento proporcionado por una riquísima biblioteca que le permitió estar al corriente de todas las novedades arquitectónicas de su tiempo.

Sabatini comprendió rápidamente este axioma y desde su llegada a Madrid en 1760 acomodó sus diseños y proyectos a las necesidades y valores políticos demandados por los representantes de la monarquía y el Estado. Para ello, Sabatini no solo acudió a su experiencia en Roma y Nápoles, sino también al conocimiento proporcionado por una riquísima biblioteca que le permitió estar al corriente de todas las novedades arquitectónicas de su tiempo.

2.- The palace, the capital and the State: spaces for a monarchy

The palace is one of the most representative symbols of majesty, difficult to imagine a monarchy without a prestigious seat that would be able to reflect the values with which it wishes to be associated. Felipe V and Isabel de Farnesio understood this well and that is why they called Filippo Juvarra in 1734 so that, after the fire of the Alcázar, he would build a palace worthy of his identity. Juvarra, Sicilian like Sabatini, designed a true monument in which the court and the State had to coexist on the same roof, the palace was thus transformed into the nerve center of royal Madrid.

Carlos III imitated in Naples the model of his parents and, therefore, while Sacchetti, after the death of Juvarra, was building the new palace in Madrid, the King of the Two Sicilies ordered the construction of the colossal Palace of Caserta in 1750. Vanvitelli's project, where Sabatini intervened, demonstrates the great involvement of Carlos III with architecture. After his arrival in Madrid, the new sovereign will be intensely involved in the transformation of a capital whose space should reflect his idea and concept of government.

3.- Madrid and Sabatini. Building a capital

Madrid was in 1760 a city with many problems. The most pressing was the health and hygiene of its streets, which Carlos III, with Sabatini and Esquilache, tackled decisively since 1761. This in-depth reform went hand in hand with the creation of a whole series of urban facilities that would guarantee the needs of an increasingly omnimous State: the Royal Customs to reinforce its administrative capacity; the General Hospital to centralize medical care and the Botanical Garden to invigorate its scientific policy.

The Esquilache mutiny of 1766 modified that urban policy. The king and his ministers decided from that date to also intervene in the outer spaces of the capital. On the one hand, reforming its wall, entrances and entrances, such as the Alcala or San Vicente gates, with the aim of improving the flow and circulation of people and goods. On the other, creating, through public parks and promenades, recreational spaces that, like the Paseo de la Florida, the Prado or the Buen Retiro gardens, would compensate for the political frustrations of the people of Madrid after the riot. Both, the internal reform and the external expansion of the city, find in Sabatini one of the main protagonists of the eighteenth-century urban transformation.

4.- The Royal Palace: projects and realities

When Carlos III arrived in Madrid at the end of 1759 the Royal Palace was practically finished in its construction, but the interior had to be decorated and furnished. The king, who requested to visit him immediately, was very disappointed with the result. Consequently, its designer and director of works, Sacchetti, as well as his team - in which Ventura Rodríguez was found, were fired and Sabatini, in Naples, called in to carry out the work.

During the works directed by Sabatini, the kings resided in the Buen Retiro palace, little appreciated by both monarchs. Finally, the king and his family moved to the new royal seat in December 1764, even though the stairs were not yet finished. Carlos III soon realized that the palace was not capable of meeting all the demands of his idea of majesty and therefore entrusted Sabatini with several projects to expand the palace. Although he presented different proposals, none of them came to fruition completely, despite the fact that they were necessary to accommodate his family. Carlos IV ordered Sabatini, in 1790, something much more ambitious: an «Increase» to house all the administration, Councils and ministries.

5.- The door of Alcalá

In 1769 the king asked three architects for designs for the realization of the new door of Alcalá, since the old one was too meager and did not adapt to the planned reform for the street. Those summoned were José de Hermosilla, former architect of the General Hospital and protégé of the Count of Aranda, president of the Council of Castile; Francisco Sabatini, royal architect preferred by Grimaldi, first secretary of state, and Ventura Rodríguez, municipal architect and favorite of Campomanes, prosecutor of the Council.

While we know the three alternatives presented by Sabatini and the five designed by Rodríguez, we are unfortunately unaware of those conceived by Hermosilla. Be that as it may, Carlos III opted for Sabatini, his architect, who was perfectly familiar with the Italian tradition of the urban door, traditionally used to extol the virtues of its ruler. Sabatini thus conceived an effective capital portal that, in the shape of a triumphal arch, shows the glory of the majesty of the king who ordered it to be erected.

While we know the three alternatives presented by Sabatini and the five designed by Rodríguez, we are unfortunately unaware of those conceived by Hermosilla. Be that as it may, Carlos III opted for Sabatini, his architect, who was perfectly familiar with the Italian tradition of the urban door, traditionally used to extol the virtues of its ruler. Sabatini thus conceived an effective capital portal that, in the shape of a triumphal arch, shows the glory of the majesty of the king who ordered it to be erected.

6.-Architecture and urbanism

In this section some of Sabatini's most impressive architectural projects are presented, such as the General Hospital or the Royal Customs, buildings with a great urban vocation, capable of ordering the space and imposing a monumental image of the power that builds them. All of this gives rise to later on to understand the Sabatini that intervenes in the city, already in an ephemeral way, through festive machines with a marked performative character, and in a more permanent way, with roads, doors and walls that define the environment of a town and the flow between its core and periphery.

One of his most successful and notable interventions on an urban scale is today, paradoxically, almost imperceptible, the sanitary and hygienic reform of the center of Madrid. A major and colossal work, the determination with which it was applied shows us the importance that values considered so modern already had in a past that was only apparently distant. The ignorance and disinterest with which Sabatini's work has been mistreated, therefore, does not reflect its value but simply the carelessness with which, on many occasions, the rich architectural and urban past of Madrid has been treated.

One of his most successful and notable interventions on an urban scale is today, paradoxically, almost imperceptible, the sanitary and hygienic reform of the center of Madrid. A major and colossal work, the determination with which it was applied shows us the importance that values considered so modern already had in a past that was only apparently distant. The ignorance and disinterest with which Sabatini's work has been mistreated, therefore, does not reflect its value but simply the carelessness with which, on many occasions, the rich architectural and urban past of Madrid has been treated.

7.- Intramuros, extramuros: idea, imagen y desarrollo de una capital

En el siglo XVIII, como muestra el caso de París, la muralla todavía desempeñaba un papel muy importante en la definición de la trama y organización urbana de una metrópolis. Madrid, definida por una «cerca» con múltiples puertas, aún conservaba la suya, necesaria por motivos administrativos y de orden público. Lejos de eliminar un elemento de todo punto necesario para el buen gobierno de la urbe, la monarquía empleó esta construcción para replantear una transformación en profundidad de la periferia de la villa.

Así, la reforma de las puertas y los paseos exteriores permitió que la naturaleza comenzara a cobrar protagonismo en el paisaje urbano de la ciudad, donde el río dejaba de estar marginado, integrándose ya, aunque tímidamente, en su configuración. Mientras el interior de la villa se reformó radicalmente en todos sus aspectos sanitarios y de habitabilidad, los exteriores se transformaron con el claro objetivo de convertirlos en espacios de sociabilidad ciudadana, perfecta metáfora del nacimiento de una nueva mentalidad política.

Así, la reforma de las puertas y los paseos exteriores permitió que la naturaleza comenzara a cobrar protagonismo en el paisaje urbano de la ciudad, donde el río dejaba de estar marginado, integrándose ya, aunque tímidamente, en su configuración. Mientras el interior de la villa se reformó radicalmente en todos sus aspectos sanitarios y de habitabilidad, los exteriores se transformaron con el claro objetivo de convertirlos en espacios de sociabilidad ciudadana, perfecta metáfora del nacimiento de una nueva mentalidad política.