The Shell-Haus, with view to Landwehrkanal in Tiergarten - a Berlin district, which at the time was noted for being one of the first high buildings with steel skeleton, becoming in this way in Emil Fahrenkamp’s masterpiece and of the most important office building in Weimar Republic.

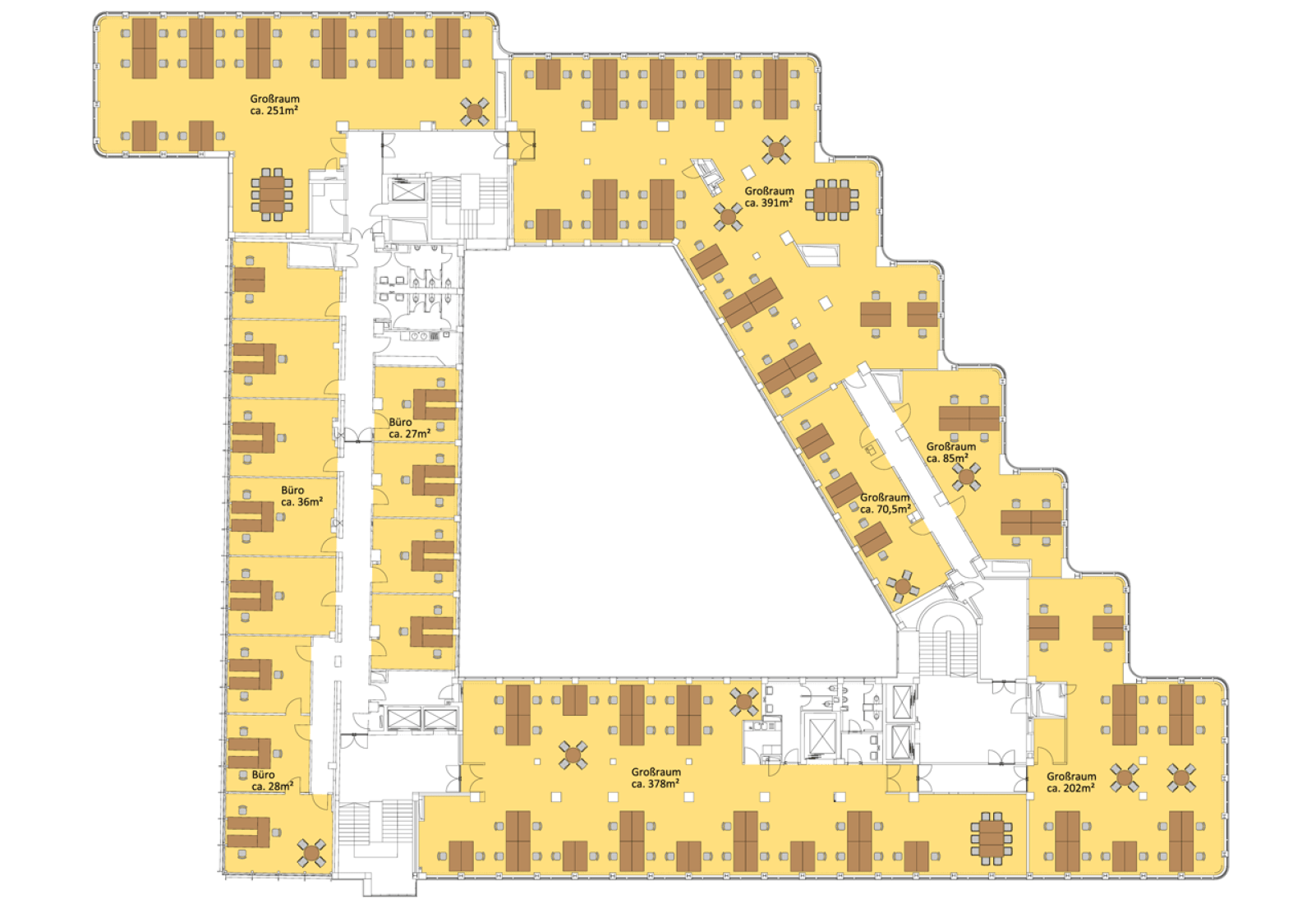

It is a building with reminiscences of German modern movement: the new objectivity, but including traditional aspects to the design. One of the most outstanding features of the Shell-Haus is its main façade. Its moves as waves in the sea, in a fluid and continuous manner, making the building becomes taller as they go along, going from 5 to 10 floors, taking this way, a strong formal expressivity. The building is formed by four wings located around a central patio.

In 1929, Shell put its Berlin subsidiary design out for tender, where five architects took part. The winner of the project was Emil Fahrenkamp. It was finished building two years later, in 1932, and it is when Shell opened it to the public. A year later, the National Socialist Party achieved power caused the fall of Weimar Republic.

During the II World War, the Shell-Haus was used by the naval high command and the basement was turned into an improvised hospital. At the end of the war and, in spite of the damages in higher floors during Berlin battle, the building survives. In 1946, the Shell-Haus becomes part of the electric company Bewag and its central offices.

The building was placed under protection as a historical monument in 1958, but despite this recognition of its architectonic importance, it was not out of the wood of the wear of the postwar period and stayed in a neglect condition, degraded and not care taken for years. Among 1965 and 1967, the Shell-Haus surroundings were reformed with the construction of two buildings. They, in a similar manner, were built with steel skeleton designed by Paul Baumgarten.

In 1997, the restoration work starts, after some years of clash over. The building work finished in 2000 with an overrun due to the excessive costs came from the need of reopening the Longarina quarry, near Rome, with the aim of stocking the travertine rock for the building façade. This same year, the building awarded a prize of monument preservation, the Ferdinand von Quast medal.

The Berlin energy supplier GASAG turned into the new owner and resident of the Shell-Haus in 2000.

After the review of the Neue Nationalgalerie by Mies van der Rohe, we continue with the Berlin tour. We approach two blocks forward and find Emil Fahrenkamp’s masterpiece: the Shell-Haus.

More information

Published on:

May 6, 2016

Cite:

"The Shell-Haus: Emil Fahrenkamp’s masterpiece" METALOCUS.

Accessed

<https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/shell-haus-emil-fahrenkamps-masterpiece>

ISSN 1139-6415

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...

Loading content ...