She earned her bachelor of arts from the University of Chicago. After graduating in 1951, she enrolled at Yale University’s School of Drama where she studied acting. While at Yale Pattison enrolled in Josef Albers’s color theory course, Interaction of Color.

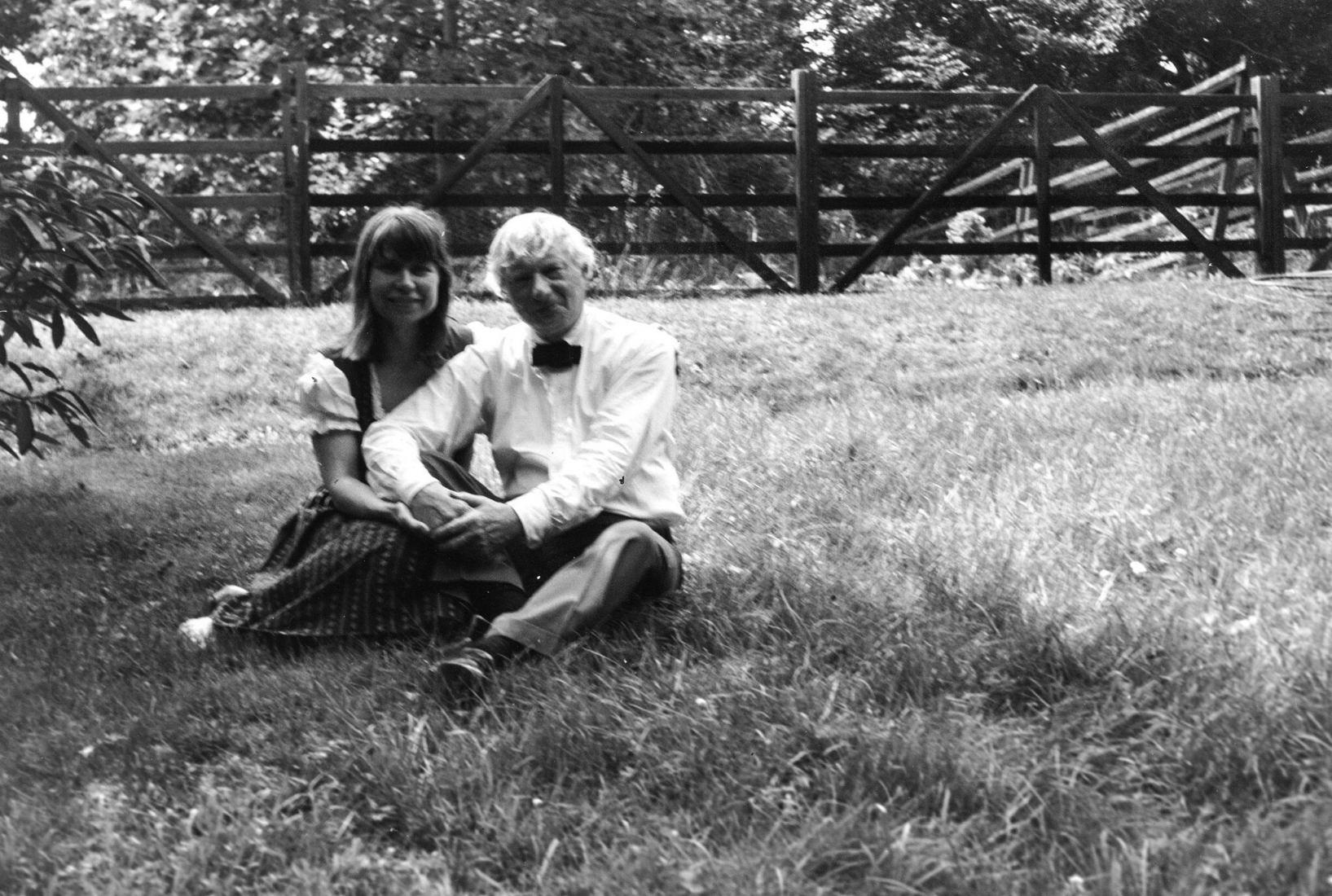

There, in New Haven, in 1958 was where she met Louis Kahn at the Wahldorf, a nearby New Haven diner. She crossed paths again with Kahn at a dinner party she attended with Robert Venturi, where she says her romantic partnership with Kahn began. Kahn played an instrumental role in Pattison’s life, encouraging her studies in landscape architecture and fathering her son Nathaniel in 1962.

In 1963 Pattison began a year-and-a-half-long apprenticeship in the office of landscape architect Dan Kiley in Vermont then enrolled in the landscape architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Fine Arts. She launched her career in the office of George Erwin Patton, where she worked until 1970. That year, she started to work with Louis Kahn at his office at 1501 Walnut Street in Philadelphia. There she collaborated with Kahn on the design for the grounds of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, then later, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, in New York’s Four Freedoms Park.

Pattison played an important role in the creation of Louis Kahn's landscaping for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress (public domain).

After Kahn’s sudden death in 1974, Pattison opened her own landscape architectural practice while still collaborating with Patton on occasional projects. Her projects included landscapes at private homes such as the Haas Residence and a master plan for the Hershey Food Corporation’s Pennsylvania headquarters. In 2016 she was inducted as a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Pattison authored the essay "Maine Landscapes: Design and Planning" on the work of her role model Beatrix Farrand, who similarly paved the way for women in landscape architecture. Pattison’s reflections on her life with Kahn were published in October 2020, during the Covid pandemic, Harriet published, "Our Days Are Like Full Years: A Memoir with Letters from Louis Kahn."

The Cultural Landscape Foundation has a comprehensive Harriet Pattison Oral History interview that can be found here, along with a reflection from her longtime friend and TCLF President Charles A. Birnbaum.