Until a few decades ago, the city of Rotterdam had always been defined as containing a high number of working people, one of the most exploited seats of the Dutch citizenry. This, in the interwar period, was only exponentially enhanced by the growth of the city's port and the arrival of new waves of workers, for whom the housing supply was neither sufficient nor accessible.

It is in 1918 when J.J.P. Oud assumes the position of director of the city's Housing Department, thanks to which new cutting-edge variables applied to large-scale social housing projects would begin to be incorporated. Among them, the two most prominent, and both by Oud himself, were the one carried out in Hoek van Holland and the Kiefhoek neighbourhood in Rotterdam, works that also shared times and styles.

It is in 1918 when J.J.P. Oud assumes the position of director of the city's Housing Department, thanks to which new cutting-edge variables applied to large-scale social housing projects would begin to be incorporated. Among them, the two most prominent, and both by Oud himself, were the one carried out in Hoek van Holland and the Kiefhoek neighbourhood in Rotterdam, works that also shared times and styles.

"The Kiefhoek stands out as an architectural island on the outskirts of Rotterdam, made up of brick houses with sloping roofs, and its conservation, although careful, cannot be compared with the buildings that surround it."

Leonardo Benevolo, 1971.1

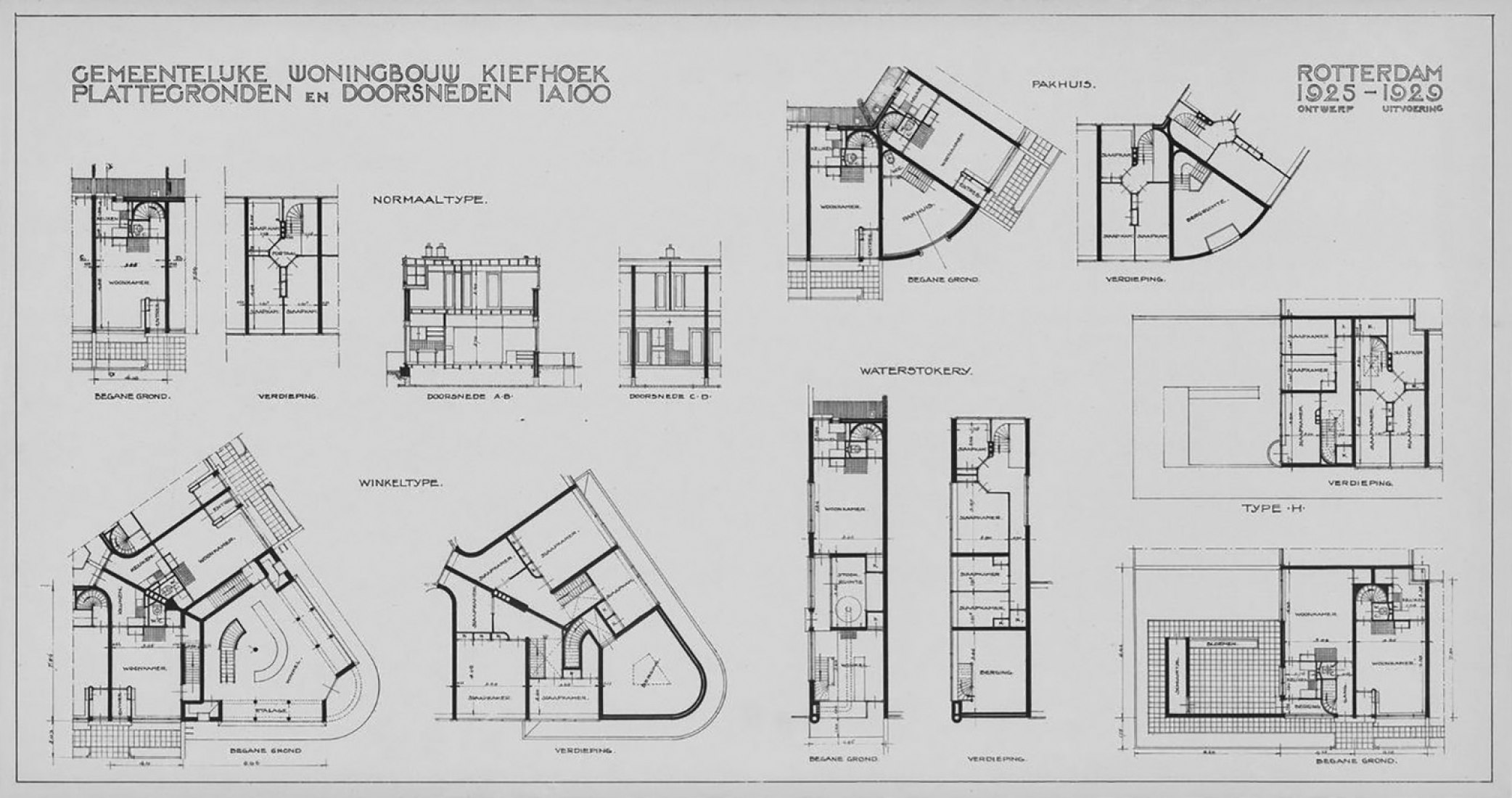

The White Town (as the neighbourhood was also known), consisted of a project of 294 homes, two shops, a water distillery, two warehouses-workshops, two playgrounds and a church, all under an urban typology of the city fragmented in the style of the German siedlungen born in those same years.

The proposal, of rather isotropic characteristics in its general perception, was limited by a fairly consolidated urban enclave in its perimeter, which forced Oud to find an introverted solution and promoted the typology of paired houses in a row set back on their interior faces. and exterior to thus gain better living conditions compared to the traditional dividing walls of the pre-existing buildings.

The set is resolved only in two levels, in opposition to many of the buildings that had been made in the years prior to the war. Oud, on the contrary, opted for semi-detached and repetitive houses to give geometric unity to the blocks that are read as complete linear volumes delimited by small entrance gardens, but that internally free up almost half of their surface for the courtyards of the heart of the block. Each of these volumes is separated from the rest by wide roads that are crossed by smaller-scale streets and that provide almost infinite perspectives of the project.

“All the security that there is in the building approach is hesitation in the urban approach. Oud feels the need to give order and hierarchy to the common spaces, but the means used are weak, although subtle and refined (...) when the urban commitment becomes a non-extendable expiration, Oud is forced to choose isolation and voluntarily reinforce traditional schemes to the point of bordering on an ambiguous neoclassicism."

Leonardo Benevolo, 1971.2

Outwardly, Oud left a clear nod to his past in De Stijl, with facades stuccoed completely in white, but with some flashes of red, blue and yellow colours in the carpentry, in a composition resolved with the most rigorous Berlaguian tradition. In the interior, on the contrary, the houses are much more loaded with these same colours and some complementary ones such as the pregnant green of the humid nuclei.

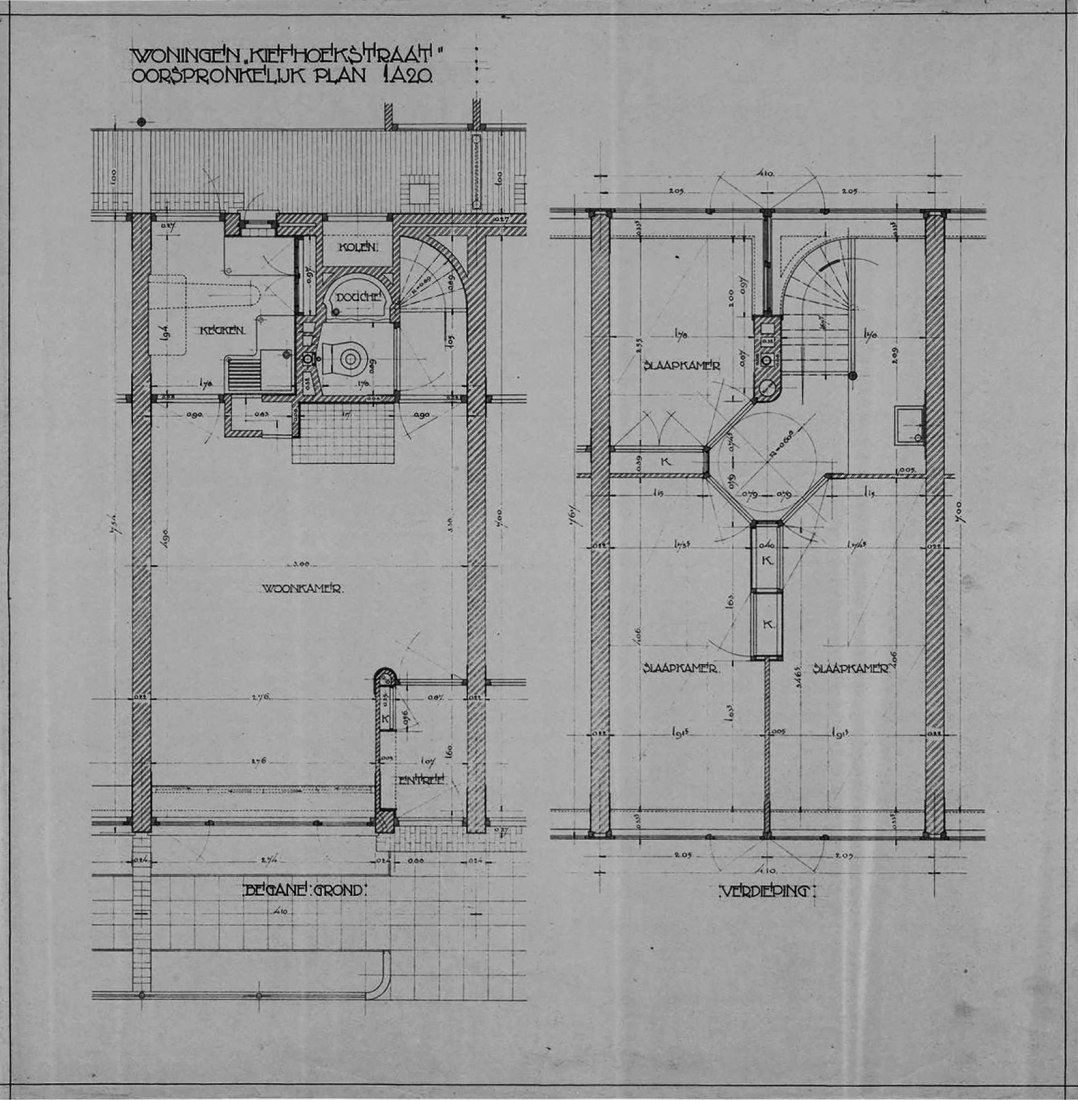

Functionally, the houses are made up of two levels of less than four meters wide (3.88 m), with a living room, a small kitchen, a bathroom and up to three bedrooms, also considering that many of the families who moved to the neighbourhood were numerous, with up to five or six children per couple. In addition, each house had a back garden designed as a small area for crops so that families could have a parallel income, or at least a lower cost of living.

For the residential area, Oud chose to design a minimal dwelling, a relatively new concept for the time, but widely disseminated by his contemporaries of the Modern Movement. If today we think that each house was resolved only in 61 m2, we might be surprised, even more so if we consider how this idea has been exploited to exhaustion today and we can easily find resolved homes (projected or forced) in less than 20 m2. But as we mentioned before, many of these residences were intended to accommodate families of eight or more. To such an extent that the architect also considered in his project the incorporation of a bed in the landing of the staircase and a shower below (although this was not finally approved, but for reasons related to excess benefits).

“Oud is the most conscientious of modern architects. Both in technical matters and in matters of design he accomplishes results less by startling strokes of imagination than by a cumulative process of refinement. In many respects the least drastic innovator among the European leaders he has advanced as does a craftsman by dint of taking infinite pains."

Modern architecture: international exhibition, 1932.3

This resolution of the Kiefhoek neighbourhood allows us to recognize a type of housing that Oud would later use (since 1926) to respond to the order of the Deutscher Werkbund with the project of the five houses in a row in the Weissenhof. It would be, finally, the accumulation of projects of the 20 that would lead the architect to be recognized worldwide and to be widely disseminated, for example, in the 1932 International Style Exhibition, led by Philip Johnson.

Finally, as a cause of the low maintenance placed on the complex and a structure that could not respond adequately to the passage of time, the working-class neighbourhood of Kiefhoek was demolished in 1978, to later be rebuilt, with some modifications, between 1989 and 1995. The process was left in the hands of the architect Wytze Patijn, who chose to combine some of the houses to provide larger spaces and in line with the requirements of the time. Beyond this, the exteriors maintained their original characteristics, only changing the uses of the stores for spaces for community activity, and a house-museum that was the only one of them that preserved the interiors as designed by J.J.P. Oud in 1926.

NOTES.-

1- BENEVOLO, Leonardo (1971) History of modern architecture. Fifth part: The modern movement. chap. XIII. The formation of the Modern Movement. 4. The Dutch heritage: J. J. P. Oud and W. M. Dudok. P. 507.

2- Ibidem. P. 508.

3- Modern architecture: international exhibition (1932) Exhibition catalogue. P. 96. New York. USA: MoMA.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-

- BENEVOLO, Leonardo (1971) History of modern architecture. Fifth part: The Modern Movement. Chap. XIII. The formation of the Modern Movement. 4. The Dutch heritage: J. J. P. Oud and W. M. Dudok. Pp. 501-514. Barcelona. Spain: Editorial Gustavo Gili.

- GARCIA GARCIA, Rafael (1995) Del bloque residencial al bloque lineal. Las propuestas de vivienda de Oud. Cuaderno de notas. N°3. Madrid. España: E.T.S. Arquitectura (UPM).

- GOLDHAGEN, Sarah & GÓMEZ, Juan (2008) Algo de qué hablar: Modernismo, Discurso, Estilo. Bitacora Urbano Territorial. Vol 12. N° 1. Pp. 11-42. Bogotá. Colombia: Universidad Nacional de Bogotá.

- GONZÁLEZ CAPITEL, Antón (1996) La arquitectura en Holanda al margen y después de las vanguardias. En Arquitectura europea y americana después de las vanguardias. Pp. 391-412. Madrid. España: Espasa-Calpe.

- WIŚNICKA, Anna (2011) New Architecture for a New Man. De Stijl and the Process of Redesigning Architecture in the Age of Modernism. Neerlandica Wratislaviensia. Vol. 20. Pp. 175-184. Wroclaw. Poland.