The proposal changes the space of the pavilion through a concept dear to Mies van der Rohe: the dilution of the separation between painting, sculpture, design and architecture, to then activate a dialogue between the multiple narratives of the local history.”

The central piece consists of a set of translucid displays, made out of silk, and meticulously distributed along the glass panels. Depicting the few surviving photographs of the original building which served as models for its reconstruction, they confront the viewer with a superimposition of past and present. Offering, thus, a composite perspective on the building and the outside garden.

The artist has also created a set of prints on plywood displayed on supports that use the same kind of travertine stone as the Pavilion’s floor. Appearing at first glance as completely black monochromes, these images depend on the movement of the spectator's body (and gaze) to reveal themselves in tenuous contrast. A sound piece installed in the garden completes the intervention, offering a multi-layered account on the work of the architect and his collaborator Lilly Reich.

Redondo’s interest for the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion arose since architecture is a recurrent topic in his artistic production as shown in works such as The Glass House (2008), Memory from Brasilia (2012), Façade (2014) and Detour (2015) among others.

The Opacity of the Modern by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill

“There is a gap in time and in the image that the Pavilion reflects (as in a mirror - in negative) that interests me.”

Laercio Redondo (1).

“The Right to opacity would not establish autism, it would be the real foundation of Relation, in freedoms. (…) The Opaque is not the obscure (but) that which cannot be reduced.”

Édouard Glissant (2).

The intervention ‘The simplest thing is the hardest to do' by Laercio Redondo at the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion, or better known as the Barcelona Pavilion, is part of an ongoing investigation by the artist into the cracks, erasures, and injustices, that hide behind the “luster and pump” of art history and architecture. (3) In his projects, the omissions and fissures are “revealed” to complicate not only the stories and truths that we know and repeat, but to inform dialectically the present in the past in both critical and poetic ways. Redondo works with the archive, and for every project, such as this one, he does extensive research; nevertheless, his investigations elude the production of academic knowledge proving or disproving a theory; he does neither want to produce ‘transparency’ of distinguishable information, nor reveal an ultimate truth. Instead, he creates a performative opacity. The writer, poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant (Martinique 1928- France 2011) describes ‘transparency’ as a colonial construct by which universal absolute truths are established thus creating totality and immobility, relegating any difference to the margins. The “difference” in the Barcelona Pavilion, may be described as the long omission of Lilly Reich as the shared author of the pavilion; or -as Redondo pinpoints-, the invisible labor of the builders of the pavilion, most likely poor workers or migrants, as it was the case for the construction of the city of Brasilia in 1960; or the ideological and commercial reasons for its creation in 1929, for its destruction, and for its reconstruction in 1986; or the role of the sole sculpture in the pavilion, The Morning, 1925 By Georg Kolbe's (Germany, 1877-1947) an idealized female figure of stretched arms and lowered gaze (while the brilliancy of Lilly Reich was made invisible) embodying the aesthetic ideal of classical modernism, - in apparent contradiction with avant-garde modernism of the pavilion- that soon came to represent (in Kolbe) a favorite aesthetic style for Hitler’s nationalism; or the absence of the organicity and liveliness of the plants in the 1986 pavilion, or the nationalist underpinnings behind the fact that both pavilions “were political projects, with analogous relations and aspirations;” to announce in 1929 a post First World War new Germanic ethos of modernity and progress, and in 1986, for Spain/Barcelona to highlight a post Franco era of cosmopolitanism. In his intervention, Redondo, delves into these differences.

As a Brazilian and Latin American, Redondo has the advantage and urgency of distrusting metanarratives, given the long history of the dysfunctional relationships between political reality and artistic modernity in Latin America and particularly in Brazil. It follows that his interest in the Pavilion, does not lie in asserting its status as a canonical monument to modernism, but as a catalyst “to understand various problems and erasures in the Modern Movement, since its beginning.” The Barcelona Pavilion, as well as other architectural and urban models in Latin America such as the city of Brasilia share similar ideals, and what further unites them, is “catastrophe;” a sequence of disastrous events: the New York Wall Street Crash of 1929; Germany’s Nazi regime (1933-45), Spain’s Franco dictatorship (1939-1975) and Brazil’s dictatorship (1964-85). Modernity is inevitably intertwined with political and social history, but art history, as well as subsequent perspectives and uses and representations of this modernity by society have tended to erase the ‘differences’ and create a “transparent” stable and perfect conception of the modern; a pinnacle of progressive ideals that suppresses other histories. Redondo instead sees “a phantom, a shadow of the original building.” For him “today the Pavilion still reflects its past. Its ghosts remain present, as if trapped in a mirror in negative.” It is the phantasmagoric invisible presences that Redondo reveals through the performative opacity of his intervention.

As the original floor plans were lost, the pavilion was rebuilt in 1986 without dependable or precise drawings, and with only thirteen black and white original photographs of the 1929 pavilion for reference. As Remei Capdevila-Werning indicates, “A notation -a score, a script, an architectural plan -is abstract and “defines a work solely in terms of its necessary features.” (4) The way the incomplete architectural plans were interpreted in its reconstruction was by completing and perfecting the “ideal character” of the Pavilion, thus rebuilding it as a unique model of “teleological” modern architecture, “a very specific kind of modernity: a modernity associated with formalism, autonomy and purity” (5) where the social, political, and cultural contexts have been erased. The reconstruction of the Barcelona Pavilion was an exercise in restauration, a discipline that is enormously complex, as important decisions are often made without having the necessary information about the original work, or decisions are made to erase specific material and ideological aspects of its history. This is the case of the restauration of for example the Sistine Chapel, 1481 ended in 1994, that in restoring the “original” vivid colors of the frescoes, it changed forever our understanding of this monument; or the difficult restauration unveiled in 2012 of the mural America Tropical by David Alvaro Siqueiros, painted 1931 in Los Angeles and whitewashed almost immediately as an act of censorship, that resulted in a subdued rendering of this political work, particularly compared to the striking figurativism of the original black and white photograph of this mural. The reasons for highlighting or downplaying certain aesthetic aspects or moments in the history of a monument or work are a mixture of ideological and aesthetic decisions that are contextual to their time, site-specific, and loaded.

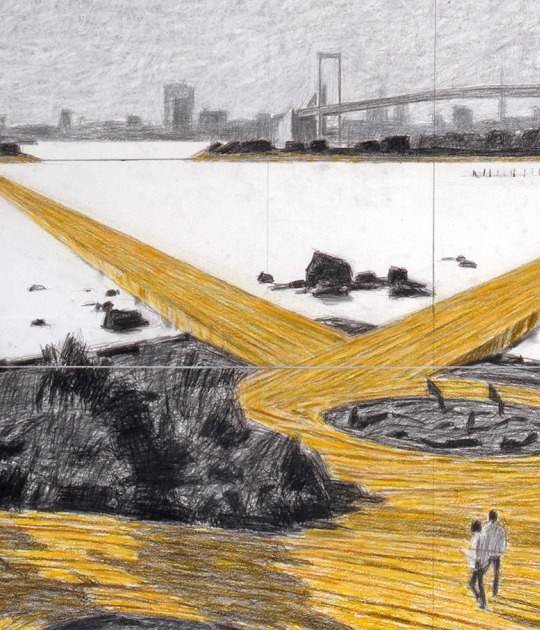

Opacity is a different type of exercise from restauration or reconstruction that aims to create a "transparency" -a truth- even when is false; instead, the archaelogy of time and materiality that Redondo unearths creates opacity, that according to Glissant is the “subsistence within an irreducible singularity”, where “opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics.”(6) For this intervention, Redondo juxtaposes on the architectural structure of the building photographs printed in silk of the original building in 1929 and new photographs taken by the artist of the 1986 pavilion. The overlay of the two registers creates a tension that reveals not only the transformations that have taken place, but “the permanent architecture”, i.e both the formal and functional mutations of the building versus the illusion of authenticity of the reconstruction.

Printing the photographs in silk have several purposes, firstly to intervene the building subtly without exerting the violence of a new truth or the pretense of a correction, secondly to offer the spectator the performative freedom of participation, interpretation and reconstruction of the pavilion, and thirdly to pay homage and make visible Lilly Reich for her unique expertise with textiles. Ultimately, as the artist explains, the silk is a metaphor, for “silk prints resemble cloudy landscapes of memory, images caught in the wind.” The artist makes a second important intervention by creating black monochromes on wood and travertine marble. The monochrome dichotomy between display architecture versus as an art form occupies a special place in the history of abstraction and art, as it is a sort of eccentricity that was never a movement and is not located in one specific moment in history, though it is deemed to be a modern invention. It is in many ways the ground zero of art, a surface that may contain everything and nothing at thesame time. The monochrome may be a “perfect” embodiment of the complex layers of memory; an opaque surface where we may see ourselves reflected in it, or that it may activate different forms of awareness, and knowledge. The monochrome also may be a container and an activator of the potentiality of informed and subjective freedom. The impressions on silk or wood in the black monochromes juxtaposed to the pavilion use “the reproducibility in trying to expand the limit of the image by its opacity.” Redondo’s monochromes are engravings of photographs of the new pavilion in serigraphic technique, similar to the daguerrotype of the 19th century, a precursor to the photographic reproduction. At first glance the black monochromes are perceived at totally abstract, but as the spectator moves and interacts with the space and the installation, may discover the images of the pavilion, and therefore actively participate in the interplay (and tensions) between the visible and the invisible the artist is exposing about the erasures of the history of the building. Going back to Remei Capdevila-Werning’s indication that an architectural plan is abstract, it is fitting that Redondo recurs to abstraction to interpellate the modern nature of the pavilion, as well as the forceful and ultimately subjective interpretation of the drawings to underscore a perfect modernity; but also, importantly, to highlight the potentiality of the abstract to reveal something beyond the over-determination of the known and the recognizable.

In many ways Redondo creates the inverse to the overvisibility and assertiveness of the new Pavilion, by proposing invisibility at first, and then a performative opacity, adding layers of complexity to the monument.

The artist explains: “the interest in these images can happen exactly because of their opacity, due to the total lack of affirmation of an image at first.” This opacity as Glissant proposes does not mean the dissolution or the denial of the Barcelona Pavilion, but as if “weaving fabrics”, in weaving the untold histories into the present, it creates a dynamic embodiment of the materiality, ideology, complexities, and erasures of the building shaping a relative model for modernity, not an absolute.

One key aspect of Redondo’s intervention is the inclusion of a sound installation in the building's gardens, which deals with the history of the Pavilion and its erasures. The protagonist for the sound piece is Lilly Reich. As the artist writes, “Lilly Reich is a fundamental figure for understanding a constructive modernity that flourished (and vanished) in Germany in the early twentieth century.” She was a pioneer of modern design; an established fashion and furniture designer as well as modern exhibition designer and an architect. (7) Since 1926 she collaborated in several projects with Mies van den Rohe, and was the artistic director of twenty-five exhibits for the German representation the Barcelona International Exhibition, and the co-designer of the Barcelona Pavilion. But how did Reich come to disappear as the co-creator of the pavilion? Her absence is key to the notion of the patriarchal amnesia that makes modernism what it is; Reich is a great symbol of erased differences in the pavilion to forge an ideal of modernity, together with the poor builders, the political histories, the biased disciplines of art history in forging both in theory and practice a clinical ideology of the modern that is purely aesthetic. Here lies the importance of Redondo’s intervention, that while revealing the ghosts of the past and that “the Pavilion no longer has the same purpose and is no longer ephemeral,” he highlights the presence of Lilly Reich in the delicate silk imprints of the past and the present of the building, and in the sound piece that accompanies the spectator in their journey through the opaque intervention by the artist. Laercio Redondo created not only a veiled theatricalization of the past highlighting the contradictions between the original intent of the pavilion, versus the new idealized reconstruction, as well as the reverberations of the tragic histories that befell both Germany and Spain while the pavilion was only a ruin; but he also underscores an inconspicuous parallel history of Brazilian modernism and the political failures that lead to dictatorship in Brazil and the de facto failure of modernism and modernity -as stable ideals- there and for some time, perhaps forever, also in Germany and Spain, and we may say in much of the world, in light of present day global political turmoil.

NOTES.-

1. Personal correspondence with the artist August 20, 2020. Unless otherwise stated, quotes from the artist are from this correspondence and personal writings of the artist for the purpose of our exchanges during the month of July 2020.

2. Édouard Glissant, “For Opacity” in The Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 190-191.

3. Redondo has explored some important moments and monuments of Brazil’s own history such as “Contos sem Reis” (Tales without Kings) at Casa França Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 2013 and “Relance” (Recast) at Pinacoteca do Estado, Sao Paulo, 2018. Redondo has also explored Athos Bulcão´s interventions in Oscar Niemeyer´s architecture in projects such as Memory from Brasilia, in Galeria Silvia Cintra + Box 4, Rio de Janeiro, 2012.

4. Remei Capdevila-Werning, “Every Difference Makes a Difference: Ruminating on Two Pavilions and Two Modernities” in Mies van der Rohe: Barcelona, 1929 (Barcelona: Fundació Mies van der Rohe Barcelona and Editorial Tenov), p. 213. Edition & Coordination : Joana Teixidor / Llorenç Bonet.

5. Ibid Capdevila-Werning, p. 218.

6. Ibid Glissant, p. 190.

7. “Questions of Fashion: Lilly Reich” Introduction by Robin Schuldenfrei. Translated by Annika Fisher This article, titled “Modefragen,” was originally published in Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit, 1922. West 86th Vol 21 No1 (Spring-Summer 2014) The University of Chicago Press.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/677870?mobileUi=0