These works allow us to discover a careful project methodology, based on abstraction. Hilberseimer tries to generate proposals, in order to adapt to the European social changes of the time. This would lead him to develop a review of his previous research on the modern metropolis, transforming it into a less dense model, more diffuse and integrated in the territory. These ideas would cristalize into his conception of the New City, which would reach its full development during his American exile.

As for the criticisms and articles that Hilberseimer wrote, those where he attacked the architects for not being able to adapt to the serial industrial production that would prevail in the future stand out. The architect and urban planner superficially addressed the issues that worried Walter Gropius at that time, both in his activity as an architect and his position in the Bauhaus.

"The architecture of the last century has looked too much into the past. This deficiency has had to be corrected by all kinds of formal tricks. Not even the best architectural works have been more than attempts to use 'beauty' to camouflage necessity. Instead of demanding engineers and the industry to propose new shapes and materials that would make a new formal reality possible, the architects have made a totally senseless use of them: to replace the old ones." (2)

The pillars on which Hilberseimer articulates its urban projects are the reflection on the minimum dwelling, housing and the residential typology, sunlight and density as modeling parameters, flows and traffic as an essential element of the metropolitan condition, and lastly, the relationship with the environment which he connects with territorial planning.

Wohnstadt (Residential City), 1923

In 1925 Hilberseimer published his design of a Wohnstadt (Residential City), dating its development in 1923. Similarly in the scheme of the metropolis, Hilberseimer was interested in the residential building as the most common way of living in German cities. The residential city is a model for a satellite city of 125,000 inhabitants, linked to a metropolitan transport network and with residence as the main theme. The city consisted of 72 blocks arranged in 12 x 6 with approximately 1750 people per block. Each block has an approximate size of 40 x 330 meters. The shorter sides of each block include shops and offices, with the apartments on the longer sides of the 5-story buildings.

These apartments had always the same size and space, regardless of whether it had a street or a courtyard in between, and they were always located taking into account the orientation of the sun, facing east and west. The interior layout of the apartments was designed so that the rooms faced the patio and the living room and the stairs gave onto the street, allowing cross ventilation.

Hochhausstadt (High Rise City), 1924

In 1924 Hilberseimer designed the High Rise City, published in 1927 in his book Großstadtarchitektur. Here, Hilberseimer raised his principles on architecture and city planning. The architect studied different solutions for the problem of traffic in the Unite dStates, such as the proposal of elevated streets, being influenced by satellite cities, which he had studied and analyzed. From this study he deducts that in spite of solving the problem of housing in the surrounding area, the traffic problem continues to exist. It were these circumstances that made him dedicate his efforts to solve those problems, thus emerging his project of the Hochhausstadt (High Rise City).

This project was probably Hilberseimer's best known. The High Rise City was a model based on practical aspects, designed in terms of the existing technology, as well as the economy and the social context. The idea of Hilberseimer for the city was based on a scheme of organization of relations between parts. The housing block replaces the individual housing, so that the importance of the collective exceeds the individual. His proposal was conceived for a system with a strong central power, the city being the center of said power. The city should be the base of the organization and the states should be organized into larger units. High Rise City was a socialist city.

The city is based on a unit that contains a community. As in medieval cities in which living and working took place in the same building, in the High Rise City the activities were organized vertically in it and both systems of circulations, the vertical and the horizontal, went from home to work. The project of the High Rise City was considered by Hilberseimer to be an authentic vertical city. The city houses 120 blocks ordered in 12 x 10. Each block, of 100 x 600 m, provides housing for 9,000 people and 90,000 m2 of business space.

Period in the Bauhaus (1928-1933)

During the period in which he was working at the Bauhaus, Hilberseimer's work changed from the study of large blocks in residential cities, to devote himself to the design of mixed-use areas with high and low-rise housing. In addition, Hilberseimer changed his ideas on the best orientation for housing, obtaining as a conclusion that the best orientation for residential buildings would be south. Hilberseimer ended up becoming a critic of high density with affirmations such as "A perfect solution is only possible by renouncing the current population density of the metropolis and by an extensive decentralization of the city area."

From blocks of 5 and 10 floors to the L-shaped houses

In 1929, Hilberseimer presents a scheme of 5-story buildings for families, combined with buildings of 10 floors for singles or couples without children. The rooms were oriented east, west and south. "The blocks were arranged so that they have the largest relative solar lighting when the living rooms are assigned in both directions," said Hilberseimer.

In the 1930s, Hilberseimer became interested in single-story L-shaped houses that, according to him, combined the advantages of semi-detached houses with those of independent houses. The L-shaped houses had a garden access to all rooms while getting good insulation from neighbors and a perfect solar exposure.

Period after the Bauhaus (1933-1967)

After the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933 due to Nazi pressure towards modern architects, Hilberseimer was forced into exile, and in 1938 he traveled to Chicago to work at the Illinois Institute of Technology with his old friend Mies. At that time, the United States was experiencing the beginning of a technological and communications revolution, as well as radio, magazines, newspapers and cinema.

With this technological change, the car began to increase its importance, and in the United States there was one car for every five people. Pollution and traffic in the center of the cities led Hilberseimer to develop an alternative city proposal, the Decentralized City.

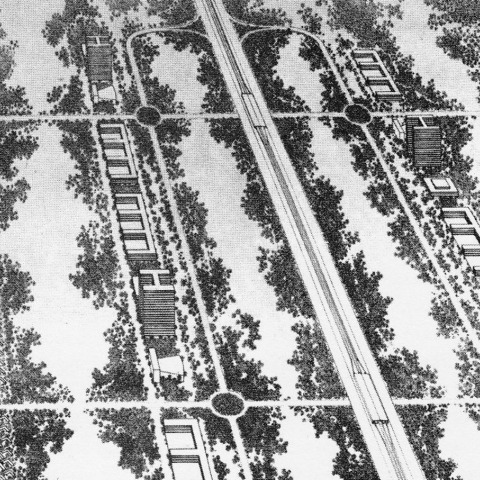

Hilberseimer's Decentralized City was published for the first time in The New City magazine in 1944. The city arose in response to the problems caused by the industrial age. The first phase of this industrialization was based on the concentration of production and separation between the city and the countryside, which is why Hilberseimer thought that the second phase should be focused on decentralization and diversification of production, both agriculture and industry, and a closer relationship between city and countryside.

Hilbersiemer created a system for low densities with units separated by uses. The units differed from each other and were combined into groups. There were three elements: traffic arteries, settlement buildings and the nature that organized it; working separately and without conflict.

The traffic arteries consisted of a combined system of open highways and closed structures, such as the spine of a fish, that created closed areas in the city and replaced intersections and corners with safe and efficient ties.

The buildings were connected to this fishbone structure. The different programs of the city were separated by a very clear area. On one side you will find industrial buildings, along the highway the administrative and commercial buildings, and behind them are different types of housing. Other programs such as schools would be located in the long green areas. In this city you could see some L-shaped houses described above.

The vegetation in the project was treated artificially to serve the user and everything is surrounded by nature, allowing a more direct relationship with it.

During his stay in Chicago, Hilberseimer also worked, along with Mies, in two specific cases, the South Side project in Chicago and the Lafayette project in Detroit, where Hilberseimer's main ideas on urbanism could be seen.

NOTES.-

(2) Ludwig Hilberseimer. G Magazine, "Bauhandwerk und Industrie" (Manual construction and industry). Berlin. 1923.