In 1912 he opened his own studio in Berlin, the same year he designs a house in The Hague for the Kröller-Müller couple. During the early years he received very few commissions, but his first works already showed the architectural line he would follow for the rest of his career. Among these works are the House in the Heerstrasse and the Urbig House.

Wolf House in 1926 by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Wolf House in 1926 by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.For Mies, 1926 was a turning point in his professional development. He was first elected vice-president of Deutsche Werkbund, a position he held until 1932, making him one of the central figures of German and European architecture in the International Modern Movement. During this time he was responsible for the planning and realization of the exhibition of the Werkbund "Housing", which would take place in Stuttgart in 1927.

The Stuttgart exhibition was the first major international exhibition of New Construction in Germany, and the most important point in the development of Mies. With the development of these initial projects, Mies discovers a new compositional design system that will be decisive in his future works. He generates free plants with fluid spaces without transitions, which constitute the characteristic "script" of his work.

A project that would crystallize brilliantly, this initial period of experiments, will be the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona Universal Exhibition (later rebuilt in 1986), where it includes his experience and knowledge of stonework, the fluid articulation of spaces, the handling of the structure and its new materials, as well as the design of the famous Barcelona Chair. This, together with the Tugendhat Mansion in Brno (1928-1930) founded Mies' universal fame.

Tugendhat House, Brno, architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, 1929. Photograph courtesy of Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016.

Tugendhat House, Brno, architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, 1929. Photograph courtesy of Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016.Like Walter Gropius, who was the dominant avant-garde architect in Germany when he was appointed founding director of the Bauhaus in 1919, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was the leading architect in Germany when he became the third director of the Bauhaus in 1930. A year earlier, his architectural designs for the Barcelona Pavilion successfully represented the achievements of the Weimar Republic at the Universal Exhibition of the Spanish metropolis.

After Walter Gropius' first offer to lead the school in 1928, he was again invited to the post in 1930 following the dismissal of former principal Hannes Meyer. Both the school and the city of Dessau hoped that Mies' authority would have a reassuring influence on the student body.

Bauhaus Dessau was closed in 1932 by a new municipal council elected by a National Socialist majority. After complex negotiations Mies van der Rohe tried to continue running the school as a private institute, based in an empty telephone factory in Berlin-Steglitz. The former School of Design was now called "Freies Lehr- und Forschungsinstitut" (Independent Teaching and Research Institute).

The National Socialists were unwilling to tolerate the continuity of the Bauhaus because of what they considered "Bolshevik orientation"; however, above all, they rejected the cultural concept of the Bauhaus. After a search of the premises, the Bauhaus was closed in April 1933. In July, the Council of Teachers headed by Mies van der Rohe decided not to reopen the school under the conditions pointed out by the National Socialists. Finally, on August 10, 1933, the Bauhaus was dissolved.

The centre underwent further transformations: new statutes were drawn up, where students were no longer represented on the Teachers' Council and all political activity within the school was banned.

While in Meyer's day, technical and economic aspects prevailed, Mies claimed the "creative process", the "how" instead of the "what". For Mies, economic and social circumstances should not be the driving force behind the relations between architecture and the issues of the moment, such as the problem of modern housing: mechanization, standardization, rationalization of processes... which took second place.

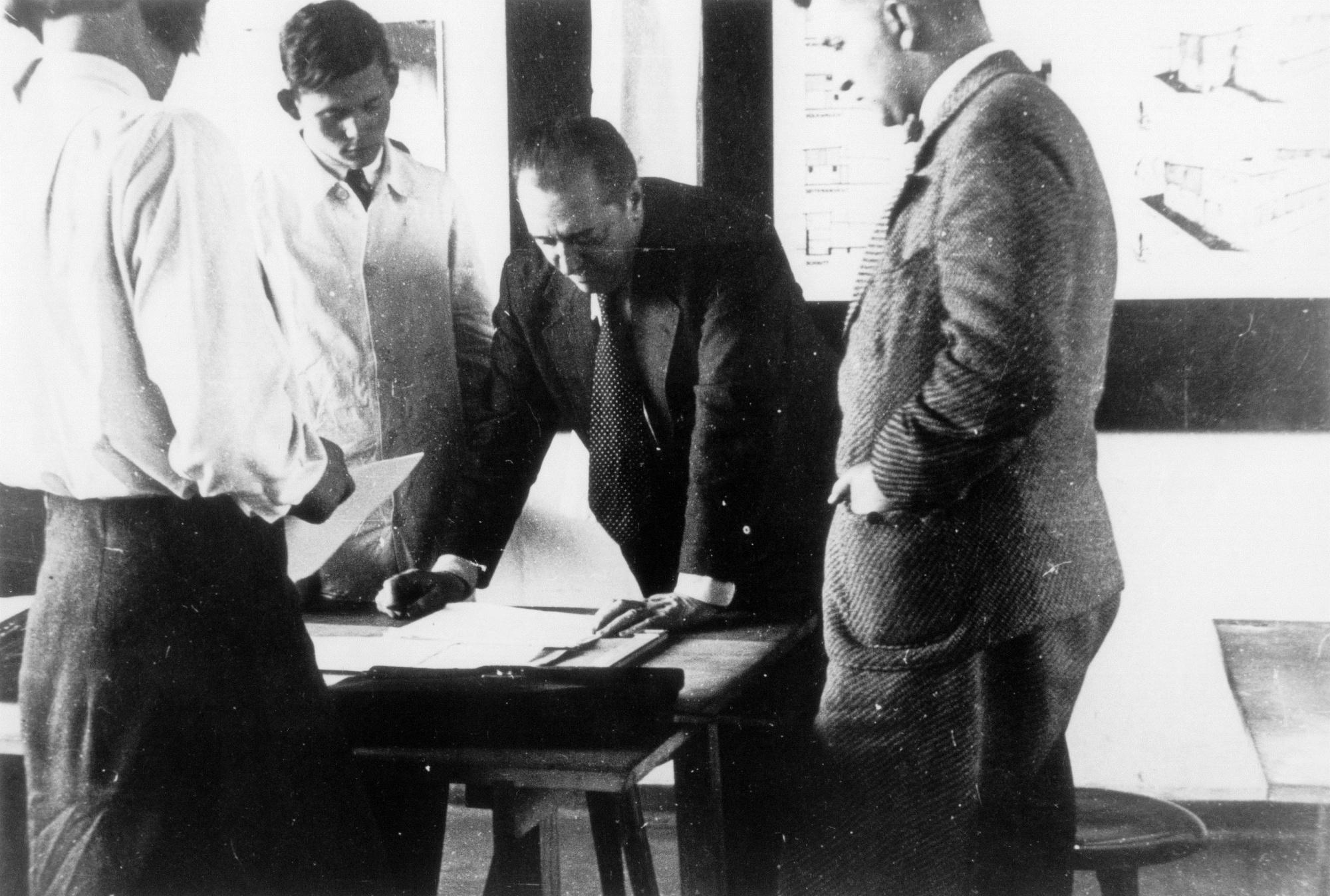

Class at the Bauhaus in Dessau: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Students (from left to right: Annemarie Wilke, Heinrich Neuy, Mies van der Rohe, Hermann Klumpp). Photograph by Pius Pahl, 1930/1931.

In 1933, most architects emigrated because of their dangerous status in National Socialist Germany. Mies flirted initially with the new authorities, until his work began to suffer many restrictions and his personal security was increasingly threatened, which led to an unsustainable situation and in 1938 he emigrated to the United States.

He was appointed director of the architecture department at the Armour Institute in 1938, which later merged with the Lewis Institute to form the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), where he would build much of the Institute's infrastructure between 1939 and 1958. One of the most famous buildings of this complex is the Crown Hall, IIT (1950-1956).

In 1940, he met his companion until his death, Lora Marx, and became a citizen of the United States in 1944. A year later, he would start the Farnsworth House project (1945- 1950). During this stage, in 1948, he projects his first skyscraper: the two towers of the Lake Drive Apartments in Chicago, which were finished in 1951.

In 1958 he projected one of his most important works: The Seagram Building in New York, a 37-storey building, covered with glass and bronze, which he built and designed together with his disciple Philip Johnson. Metal curtain façades that revealed the structure of the building by reproducing it.

New National Gallery, Mies van der Rohe, Berlin, 1968. Photograph © Branly Pérez.

The construction of the great pavilion of the New National Gallery in Berlin (1962 to 1968) is considered to be the culminating point of the principle of empty space, which consisted of a single space freed from the need for structures. It is a building dedicated to art exhibitions, consisting of a large square room built entirely of glass and steel and situated on an extensive terrace of granite slabs.

NOTES.-

(2) Ibidem (1), p. 10.

(3) Magdalena Droste. Bauhaus. Köln: TASCHEN, 2006, p. 85.

(4) Ibidem (1), p. 17.