One of the most obvious is the historical value ("historiche were"), in that these remnants bear witness to a bygone era, that of coal mining, which reached its peak in the first half of the 20th century. Taiwan was under Japanese rule. This is probably what gives the tunnels their classification if not their architectural uniqueness: the "horseshoe" sections are formed by a stone structure at the bottom, topped by a brick vault, while the entrances are built in carved stone, sometimes decorated with entablatures, pilasters and pediments. This "Beaux-Arts" style, quite anachronistic compared to the Western technical works of the same period, is representative of Japanese colonial architecture until the 1920s. If this historical value had prevailed, the project would have sought to erase the traces of the alterations that these works have undergone to restore their original integrity, but it is content to stabilize and consolidate them.

Photo of the bridge over the Keelung River (now gone; the bridge, not the river) on the day of the railway's inauguration, 1922. Photograph by Hikotaro Maehata (Japanese engineer who designed the railway).

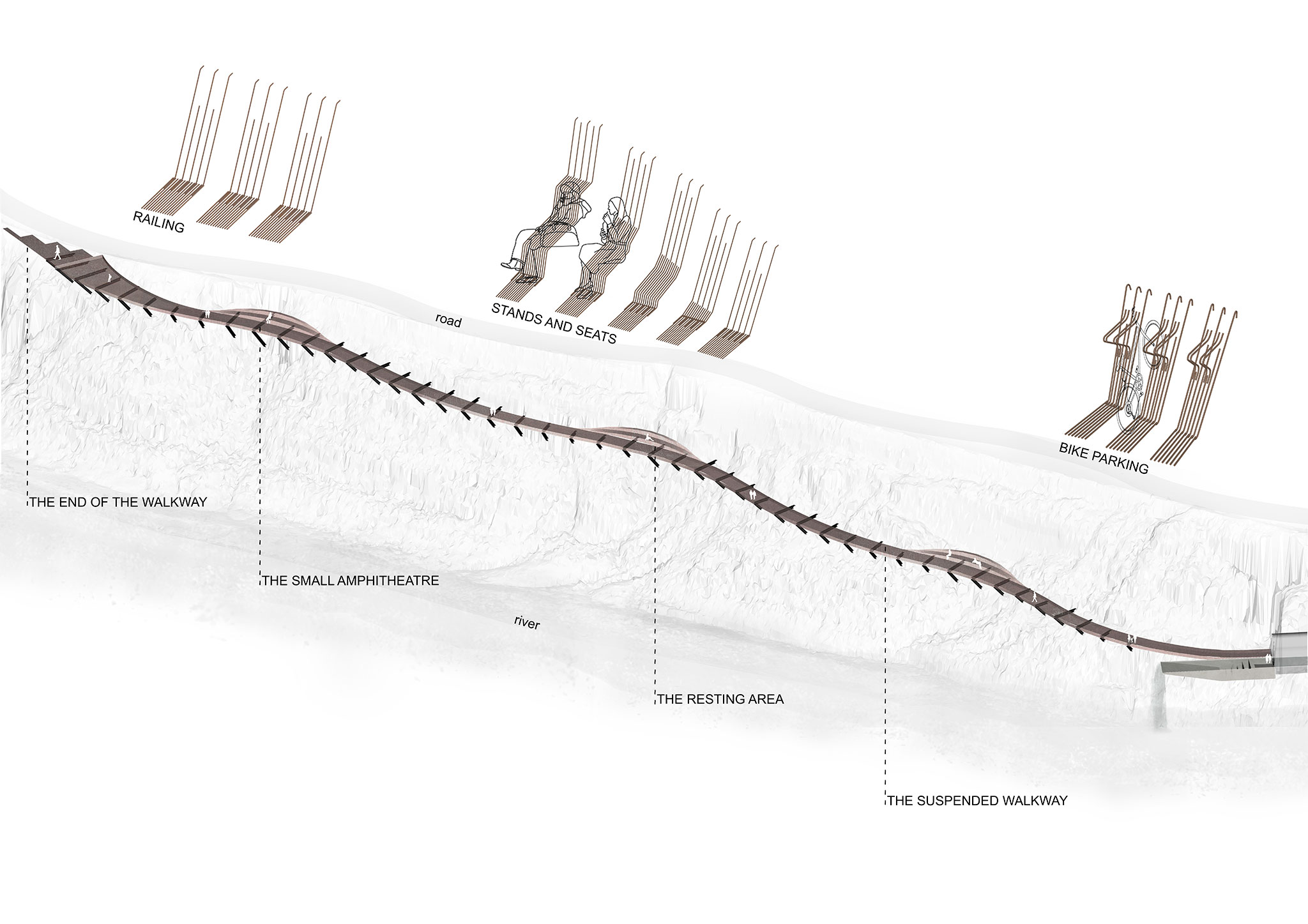

Likewise, the Dark Line does not fully recover this heritage's use-value ("Gebrauchswert") by restoring rail traffic. However, it reactivates this functionality for movements of a different nature: now dedicated to the "muscular" locomotion of pedestrians and cyclists, the new path takes advantage of the colossal effort of levelling and continuity that was previously made (although the preservation of the sedimented ground level leads to a more irregular longitudinal profile, sometimes reaching a slope of 4.5%).

It is obvious, however, that the Dark Line is based above all on the age-value ("Alterswert") of this heritage, emphasizing, recalling the words of Riegl, "the slow and inevitable disintegration of nature" 2, who already in his time pointed out that this value tended to prevail over all others and that it could attenuate not only the historical value but also the art-value, that this value tends to prevail over all others, and that it can diminish not only the historical value but also the artistic value (art-value), since both values imply the complete conservation of the remnant, considering it in the first case as a "document" and in the second as a "work."

Display. The Dark Line by Michèle & Miquel and dA VISION DESIGN.

Here, however, the art-value lies both in the ruins of the old railway infrastructure and in that of the fresh intervention.

The design of the Dark Line, very precise and adapted to the topography, refers not only to the art of the Japanese engineers of the early 20th century who designed the original work but also to that of the first engineers of ponts et chaussées (bridges and roads) in 18th century France, whose cartographic activity served to adapt the necessary geometric rationality of the infrastructure to the irregularities of the site. This dialogue is particularly virtuous in the design of the 170-meter-long footbridge, which extends the route where the bridge is missing, branching out and clinging to the cliff to connect the route to the Yuliao road, which is higher up. This solution is also reminiscent of the "Chemins volants" (flying paths) recommended in Henri Gautier's treatise on road construction at the end of the 17th century when the slopes were so steep that it was necessary to devise structures embedded in the "rock itself" 3.

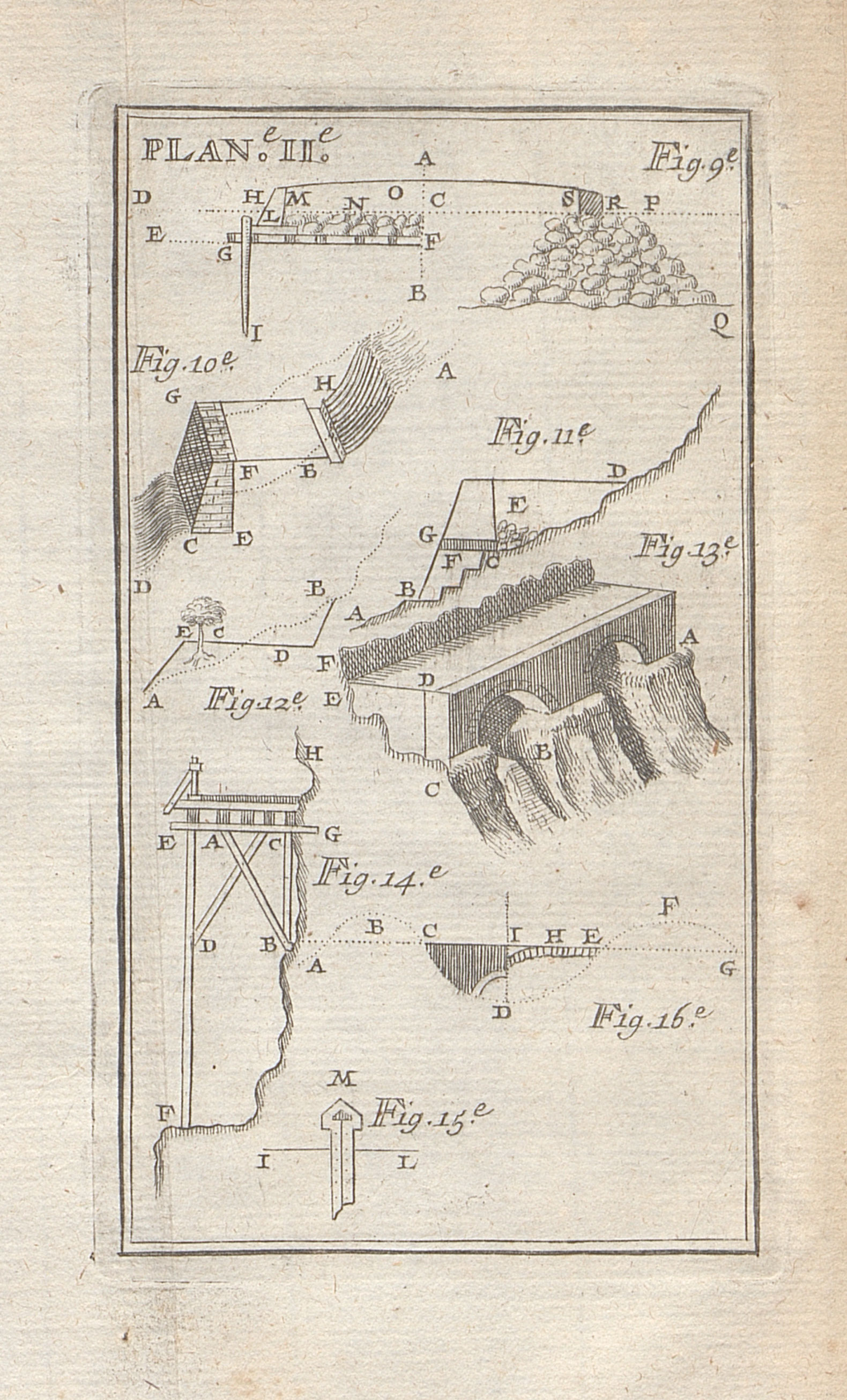

Book. Traité de la construction des chemins où il est parlé de ceux des Romains, & de ceux des Modernes, suivant qu’on les pratique en France by Gauthier Henry.

The sinuosity of its layout, made up of identical modules designed to follow the shape of the cliff as closely as possible, gives the walkway a "picturesque" character that contrasts with the straight lines connected by large radii of curvature of the railway line that the Dark Line still follows in the tunnels.

This first long sequence - most of the length of the project - marked by the succession of tunnels, can in turn be described as "sublime". This aesthetic genre, forged in the 18th century (along with "the beautiful" and "the picturesque") and based on excess, vertigo and fear, was promoted by several garden theorists of the period, such as the architect William Chambers. In his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening, the "Terrible" (equivalent to the Sublime 4) as interventions that the Dark Line seems to echo, not only because he claims to have observed them in China, but above all because they are paths, especially "vaulted passages," that crosses a landscape made up of "deep valleys inaccessible to the sun, impending barren rocks, dark caverns, and impetuous cataracts rushing down the mountains from all parts" 5. Chambers even mentions the disturbing presence of "bats", like those Michele&Miquel kept in the tunnels.

The Dark Line por Michèle & Miquel y dA VISION DESIGN. Fotografía por LU Yu-Jui, Michèle & Miquel.

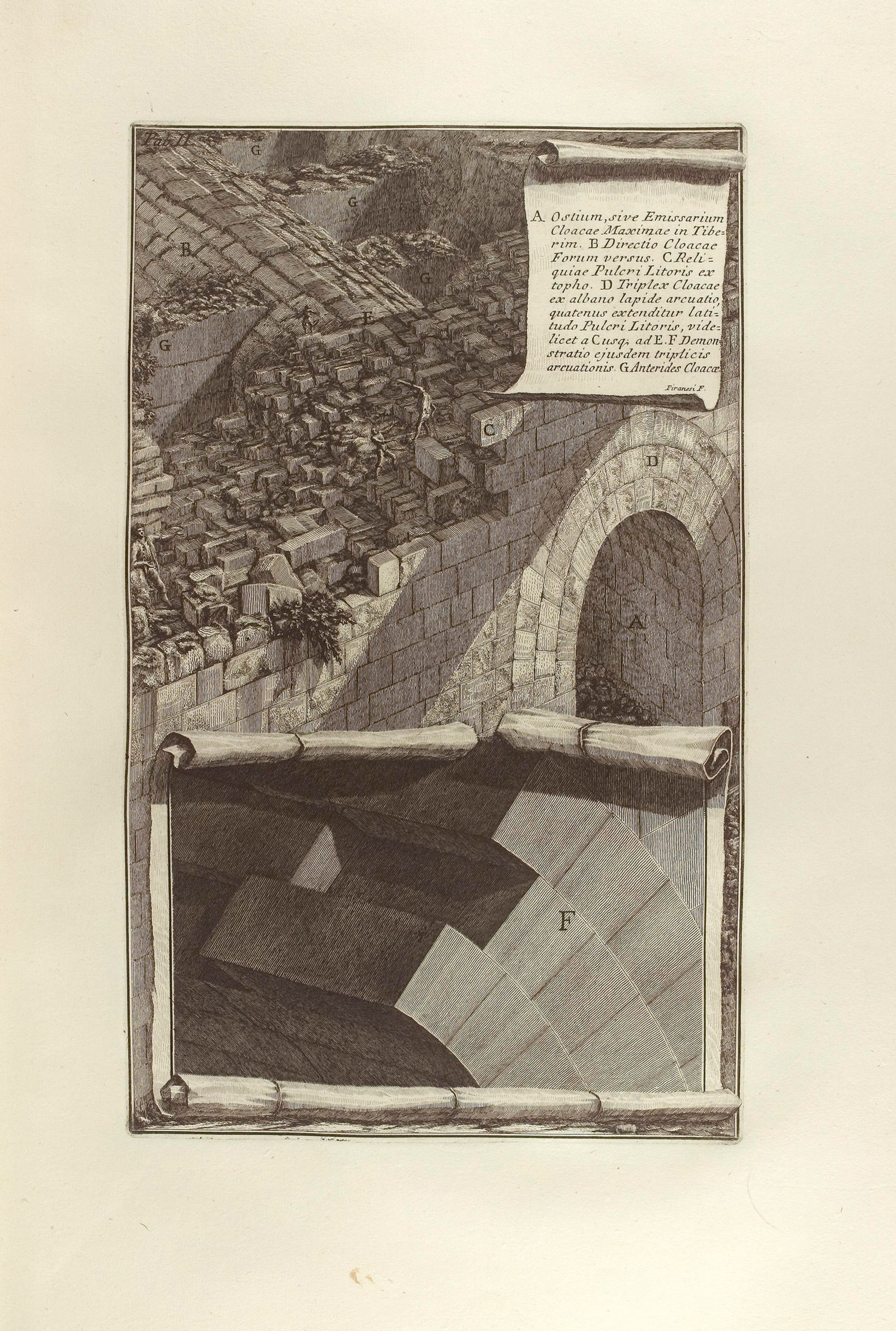

However, the sublime of the Dark Line is reminiscent of Piranesi's engravings, especially when Piranesi redraws utilitarian works: sewers, pipes and emissaries 6, where he depicts monumental vaulted galleries, sometimes in ruins, covered with vegetation, blocked by landslides and a ground covered with a layer of sedimented earth. From this point of view, in The Dark Line, the age-value does not diminish, but rather the art-value increases. On the one hand, because in the twentieth century, certain artists made the processes of wear, alteration, and entropy the very subject of the work 7 (which Riegl could not observe in 1903), and on the other, because since the eighteenth century, as demonstrated by the sublime restorations of Chambers and Piranesi, the taste for ruins had already attributed artistic value to the loss of the object's integrity and the traces of time. In this regard, Riegl noted that the sensitivity to ruins had since been dissociated from the "Baroque pathos" - which gleefully lamented the decline of civilizations - and that now "The traces of age have a soothing effect on him as evidence of the course of nature, to which all human endeavour is surely and unfailingly subject" 8.

Plank II. Gambattista Piranesi, Della Magnificenza Ed Architettvra De' Romani, 1761.

Moreover, Piranesi had already emancipated himself from a passive and nostalgic relationship with the ruins, revealing their materiality and constructive intelligibility, sometimes exacerbated by alterations and collapses, in an "affirmed continuity between the works of nature and the works of culture." 9 This type of connection is particularly evident in Sandiaoling, where the railway works - built in masonry and with a very narrow profile - were installed in the natural area without hardly altering it 10 and where, since its abandonment, the changing power of the subtropical climate has considerably reduced the border between natural and artificial elements.

The Dark Line has only taken note of this situation to propose a sublime transfiguration.

Text by Éric Alonzo

NOTES.-

1 Aloïs Riegl, "Der moderne Denkmalkultus. Sein Wesen und seine Entstehung", Vienna and Leipzig, 1903. English: "The Modern Cult of Monuments, Its Essence and lts Development." New York: Oppositions, no. 25 (Fall 1982), p. 21-51.

2 Ibid (Riegl), p. 31.

3 Henri Gautier, Traité de la construction des chemins [1693], Paris: Duchesne, 1755, pp. 42-43 and pl. II, fig. 14.

4 He associates it with the "pleasing" and the "surprising," equivalents of the "beautiful" and the "picturesque. William Chambers. "A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening". London: Griffin, 1772.

5 Ibid. p. 36-53.

6 See in particular the collection of engravings entitled Antichita D'Albano, 1762-1764.

7 See, for example, the texts and works of Robert Smithson (1938-1973), the work of Richard Serra (born in 1938) on corrosion, or more recently that of Michel Blazy (born in 1966) on natural processes (vegetation, fungus, etc.) and, more generally, Arte Povera, Land Art, Supports/Surfaces, Ecological Art, etc.

8 Ibid (Riegl), p. 32.

9 Alain Schnap, Une histoire universelle des ruines, Paris, Le Seuil, 2020, p. 611. For Bill Henson, "l'utilisation de la nature par Piranèse [...] ancre ses ruines architecturales et les soumet à la nature". Translated from English: "Piranesi's use of nature [...] anchors his architectural ruins and also, critically, subjugates them to nature". ("Unfinished Symphony: My experience of Piranesi," in Kerrianne Stone and Gerard Vaughan (dir.), The Piranesi Effect, Sydney, Newsouth, 2015, p. 261).

10 Although created in the 20th century, in a relatively late industrial age, this development had produced a “traditional landscape” as defined by Antoine Picon, characterized by the presence of “the works of man [that] were nestled in the heart of nature. This immersion, incidentally, helped bestow upon them their true meaning as extensions of the natural world, not like a prosthesis, but rather as an instrument of revelation.” Antoine Picon, “Anxious Landscapes: From the Ruin to Rust.” Grey Room 1 (September 2000), p. 66.

2 Ibid (Riegl), p. 31.

3 Henri Gautier, Traité de la construction des chemins [1693], Paris: Duchesne, 1755, pp. 42-43 and pl. II, fig. 14.

4 He associates it with the "pleasing" and the "surprising," equivalents of the "beautiful" and the "picturesque. William Chambers. "A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening". London: Griffin, 1772.

5 Ibid. p. 36-53.

6 See in particular the collection of engravings entitled Antichita D'Albano, 1762-1764.

7 See, for example, the texts and works of Robert Smithson (1938-1973), the work of Richard Serra (born in 1938) on corrosion, or more recently that of Michel Blazy (born in 1966) on natural processes (vegetation, fungus, etc.) and, more generally, Arte Povera, Land Art, Supports/Surfaces, Ecological Art, etc.

8 Ibid (Riegl), p. 32.

9 Alain Schnap, Une histoire universelle des ruines, Paris, Le Seuil, 2020, p. 611. For Bill Henson, "l'utilisation de la nature par Piranèse [...] ancre ses ruines architecturales et les soumet à la nature". Translated from English: "Piranesi's use of nature [...] anchors his architectural ruins and also, critically, subjugates them to nature". ("Unfinished Symphony: My experience of Piranesi," in Kerrianne Stone and Gerard Vaughan (dir.), The Piranesi Effect, Sydney, Newsouth, 2015, p. 261).

10 Although created in the 20th century, in a relatively late industrial age, this development had produced a “traditional landscape” as defined by Antoine Picon, characterized by the presence of “the works of man [that] were nestled in the heart of nature. This immersion, incidentally, helped bestow upon them their true meaning as extensions of the natural world, not like a prosthesis, but rather as an instrument of revelation.” Antoine Picon, “Anxious Landscapes: From the Ruin to Rust.” Grey Room 1 (September 2000), p. 66.

![Detailed plan and profiles of the works done from the Bertier ravine at the entrance to the Roches de Pierre-Aiguille to Thein [Tain-l'Hermitage], Atlas of Trudaine for the generality of Lyon, Grande route from Paris to Lyon , Route de Lyon in Provence and Languedoc, 1745‑1780. Detailed plan and profiles of the works done from the Bertier ravine at the entrance to the Roches de Pierre-Aiguille to Thein [Tain-l'Hermitage], Atlas of Trudaine for the generality of Lyon, Grande route from Paris to Lyon , Route de Lyon in Provence and Languedoc, 1745‑1780.](/sites/default/files/styles/mopis_news_carousel_item_desktop/public/metalocus_michele-miquel_dark-line_14.jpg?itok=v_Bk4lKx)