At the time of the construction of the Azuma House, in the city of Osaka, some old row houses that survived the air raids of World War II were still standing, these houses were known as machiya, and their main characteristics were the way in which they occupied most of the area of the plots in which they were located and their landscaped patios of lights that served as a point of contact with nature.

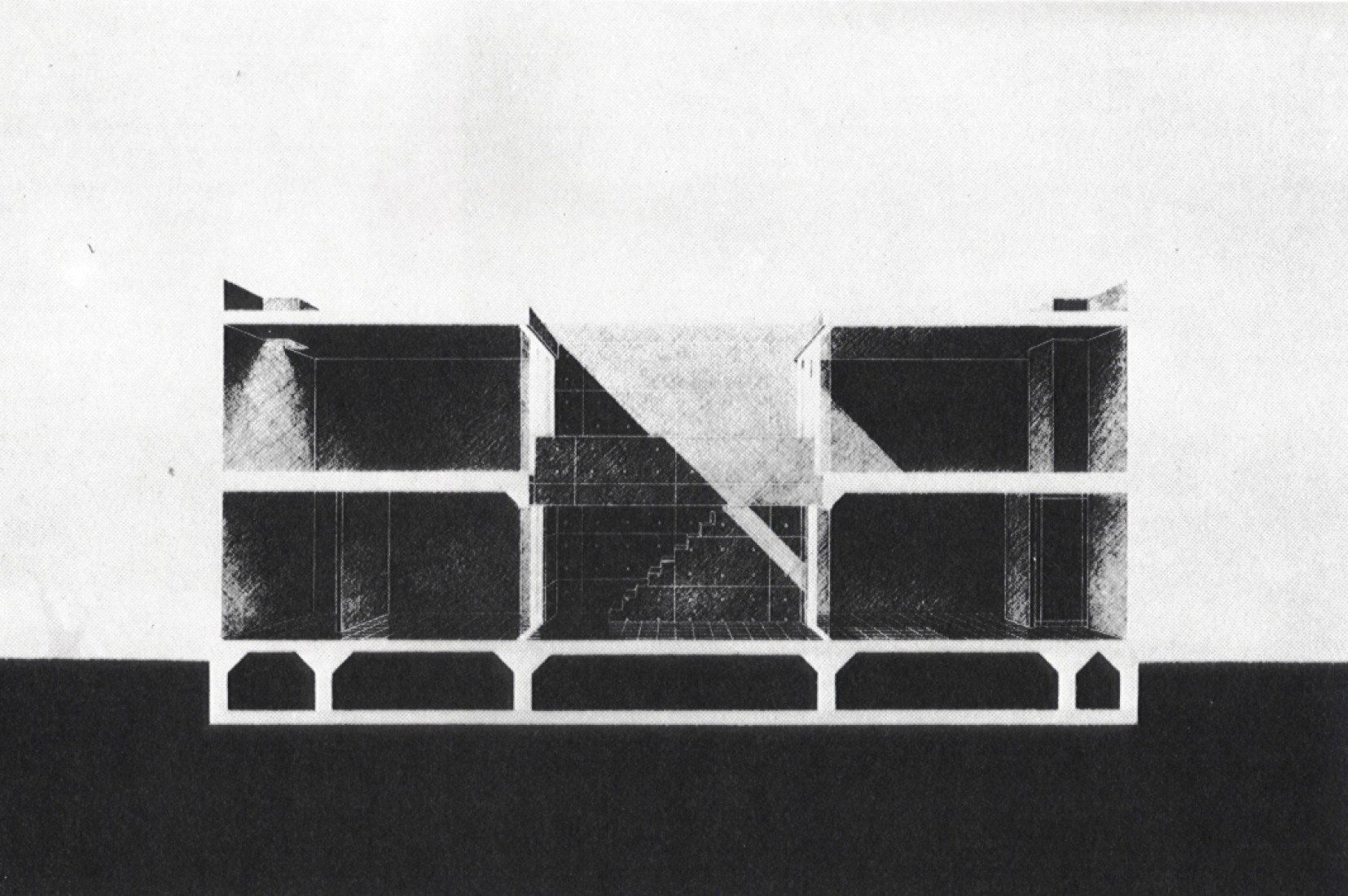

Taking these traditional houses as a reference, Ando took advantage of the conditions of the narrow and elongated plot located between party walls and opted to replace the central volume of the traditional row houses with a reinforced concrete box closed to the outside. Its rooms were now organized around a central discovered patio that allowed the passage of wind and light. The decision to turn the entire house inside the house was not random, and at that time, Ando considered the outside a hostile space and started introducing open spaces in the interior of his projects.

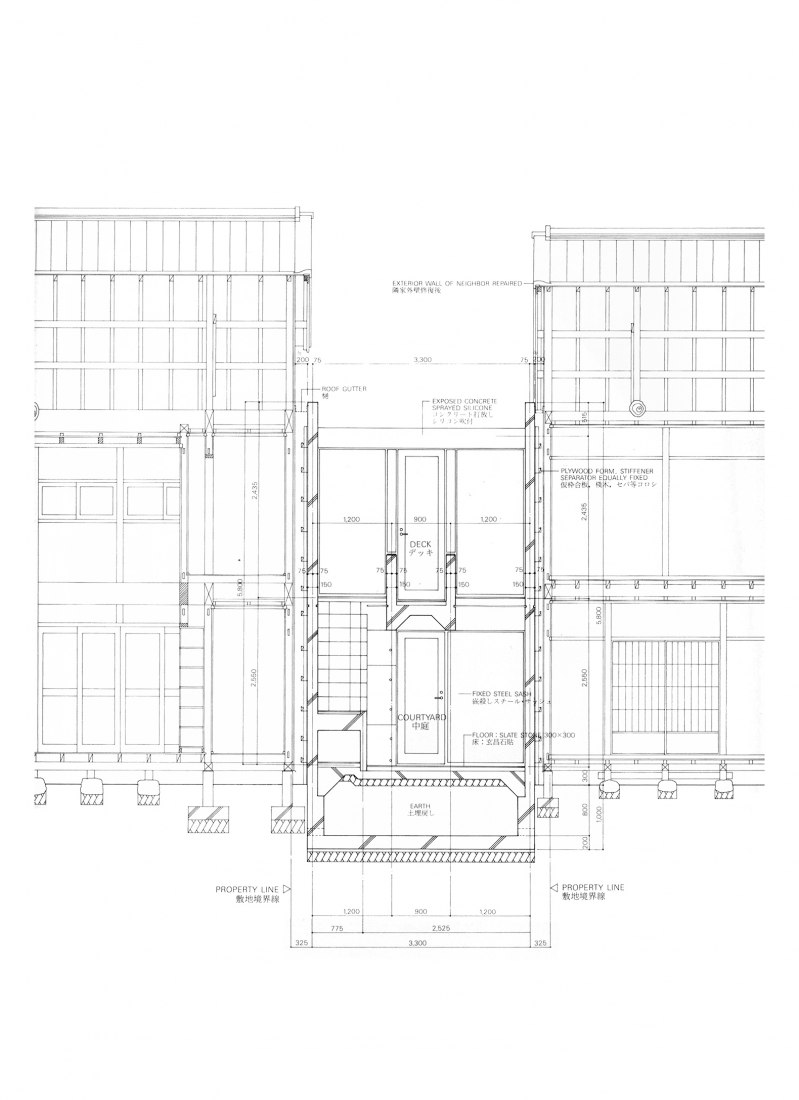

The exterior aspect of the house is characterized by its sobriety and its secrecy towards the outside, preventing at all times from being able to observe what is happening in the interior rooms. Ando dispenses with all kinds of ornament on the exterior enclosure of the house, avoiding even introducing projections capable of casting shadows. Despite this, Ando is able to recover and reinterpret the traditional idea of the threshold and does so through the access door to the house that recesses in the wall as a safe hole capable of welcoming users inside.

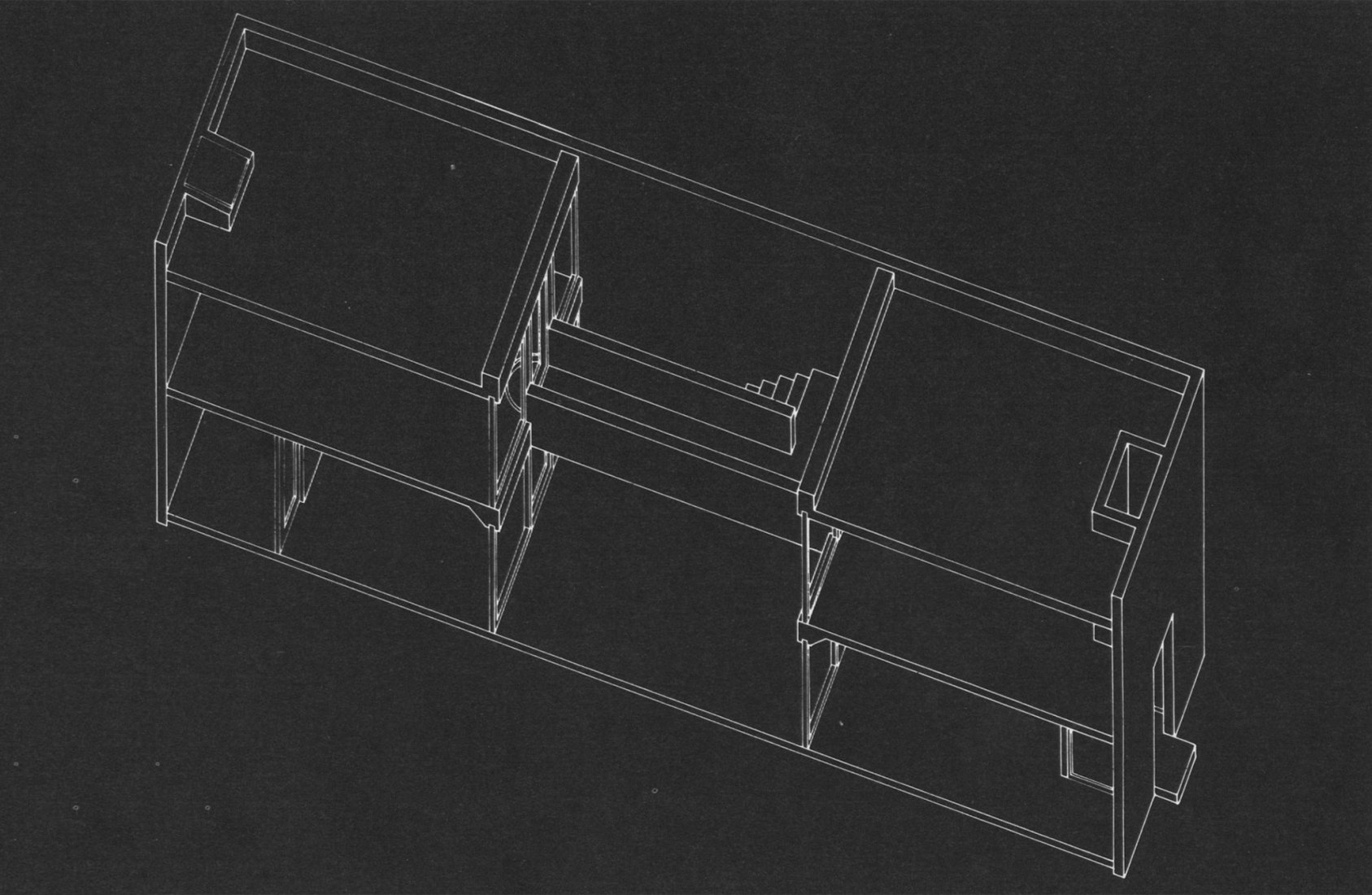

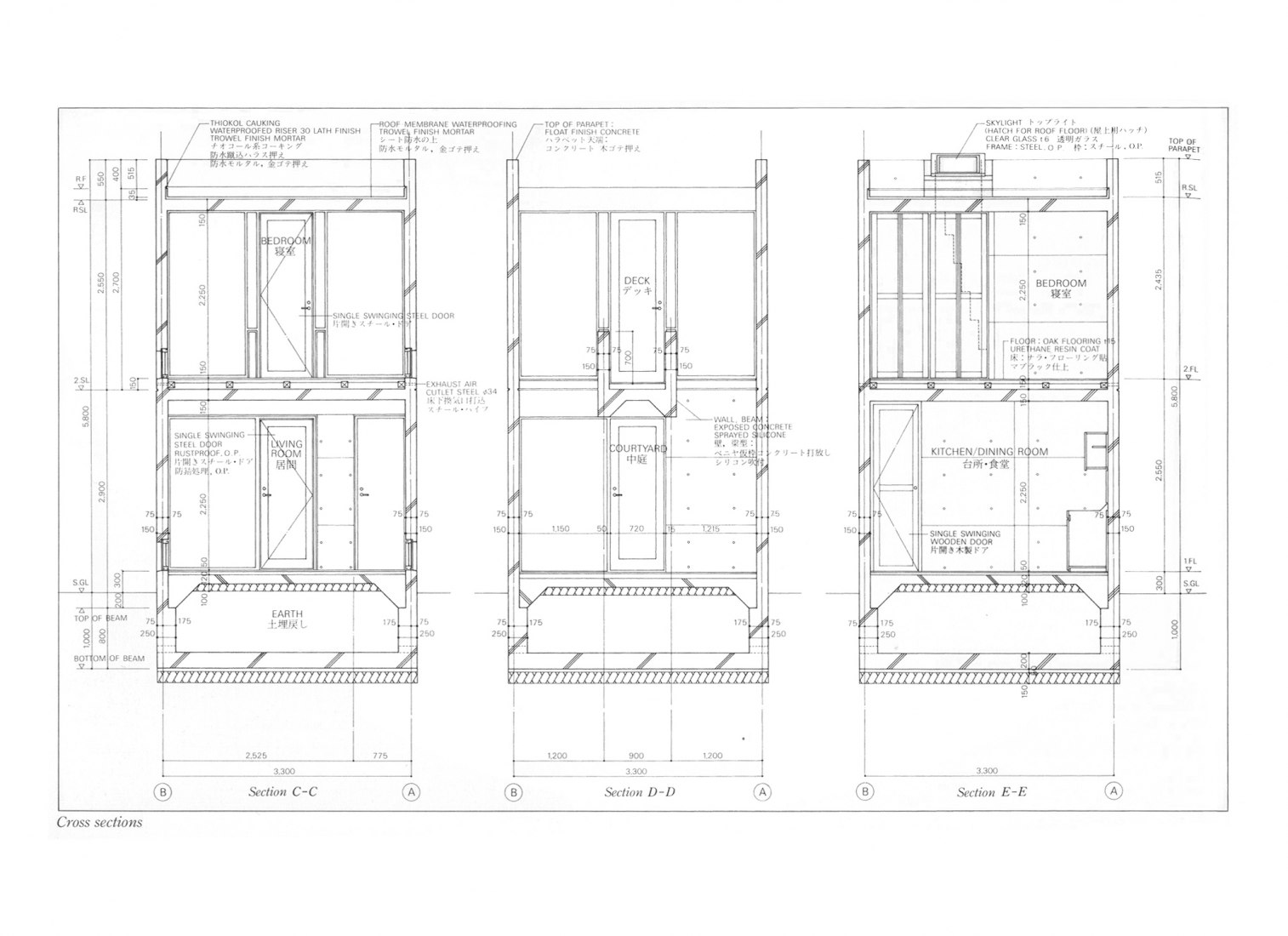

Access to Azuma House is through a vestibule with a step lined with ceramic tiles that evoke the Japanese tatakis. Once inside, the house is divided into three equal parts, being the central part assigned to the patio. The ground floor of the house contains public rooms such as the living room, the kitchen, the dining room, or the bathrooms. For its part, the upper floor is reserved for the more private rooms hosting the bedrooms of the house.

This division results in an interior that is too compartmentalized, and that is the reason why the patio is located in the central area of the house, allowing to create a larger room when joining those that are open. In this way, the central patio stands as the axis and focus of the family's daily life and, in addition to the functions of supplying light to the house, it acquires others such as, for example, constituting a spatial entity capable of compensating for its reduced dimensions.

The Azuma House project was the first step in the endless quest to harmoniously relate architecture and nature, which Ando has pursued throughout his entire career, being some of the best examples of this quest his Church of the Light or his Church on the Water. In this project, Ando eliminates all the figurative elements of nature, such as vegetation, and only introduces primary elements such as the sun, the rain, or the wind through the open patio, in what seems to be a search for the abstraction of the natural.

Although the reinforced concrete that Tadao Ando has used so much throughout his career is once again the principal material of this project, we must also highlight the use of other materials such as glass or slate, used to delimit the exterior space of the yard. Ando uses these materials since when they come into contact with natural elements such as light, rain, or air, they facilitate the kinds of connections that have been lost in today's Japanese cities.

The Azuma House was a milestone in Ando's career since it was the first work in which he introduced traditional concepts of Japanese architecture and culture through the use of totally contemporary techniques, an exercise that would accompany him in all the projects that he would develop years later. In addition, the simple composition of the house and the way in which the light gives character to the different spaces of it, synthesize in a small volume the essence of all the architecture of Tadao Ando.

NOTES.-

2.- Ibidem (1), p. 26.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-

- Ando, Tadao. (2000). «Tadao Ando: 1983-2000». Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, pp. 12-13.

- Futagawa, Yukio / Eisenman, Peter. (1991). «Tadao Ando: Details 1». Tokio: GA, A.D.A. EDITA Tokyo, pp. 12-21.

- Ando, Tadao. (2019). «Tadao Ando 0 Process and Idea: Expanded and Revised Edition». Tokio: TOTO, pp. 24-27.

- Frampton, Kenneth. (1985). «Tadao Ando. Edificios. Proyectos. Escritos». Madrid: Gustavo Gili, pp. 26-29.

- García Braña, Celestino. (1986) «Un recorrido por la obra de Tadao Ando». La Coruña: Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de La Coruña. Academic bulletin, issue 3, pp 36-47.