Close to forty cars have been brought together for the occasion, a selection of the best in each class in terms of beauty, uniqueness, technical progress, and vision of the future. Located in the center of the rooms and surrounded by important works of art and architecture, many of them are presented for the first time to a wide audience, as they had never left the private collections or public institutions to which they belong.

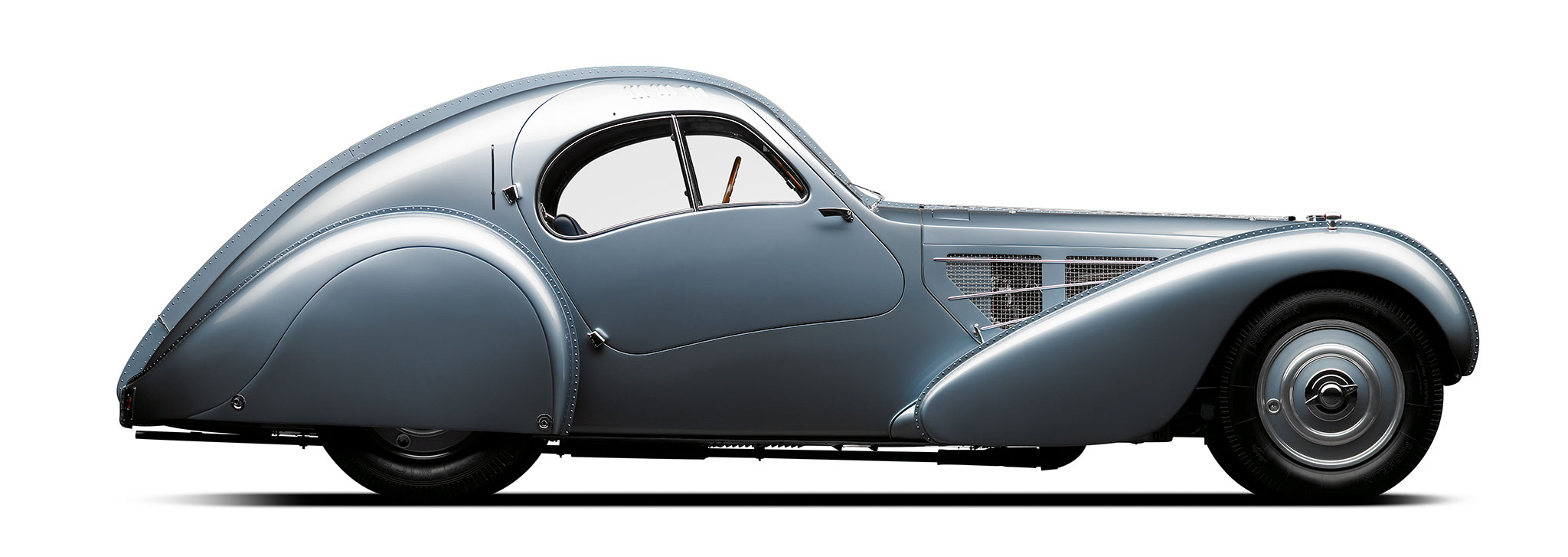

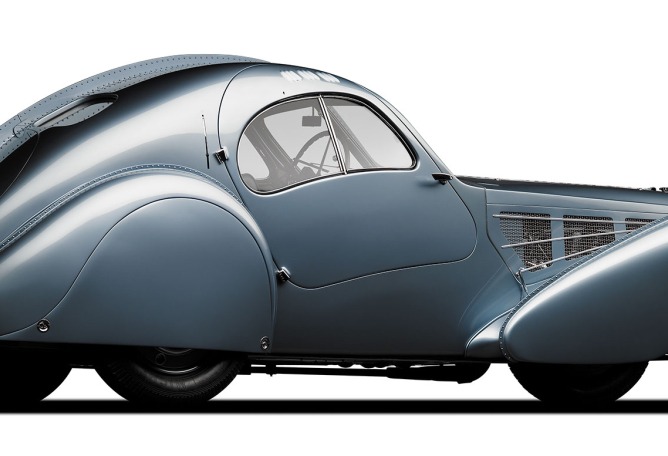

Jean Bugatti, Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic, 1936. Merle & Peter Mullin, Melani & Rob Walton and the Mullin. Automotive Museum Foundation. Photograph by Michael Furman.

ROUTE THROUGH THE EXHIBITION

Beginnings

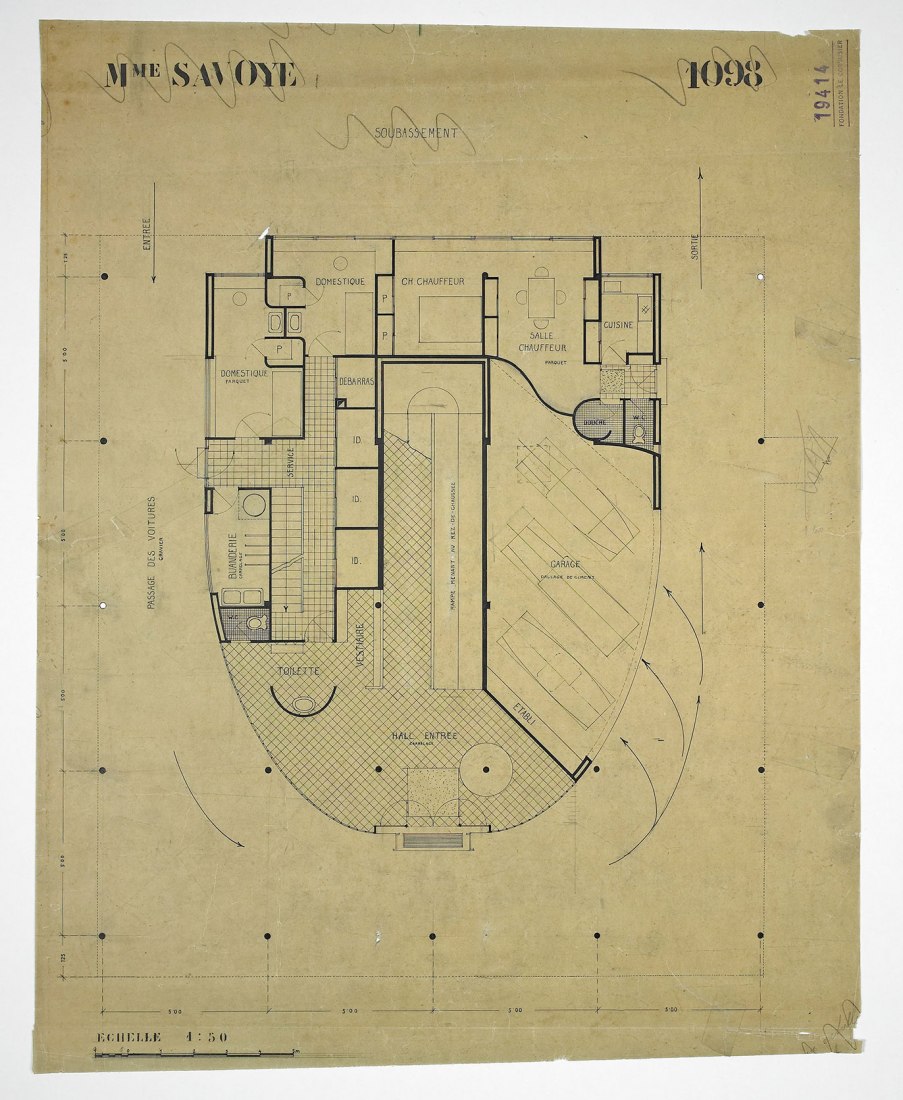

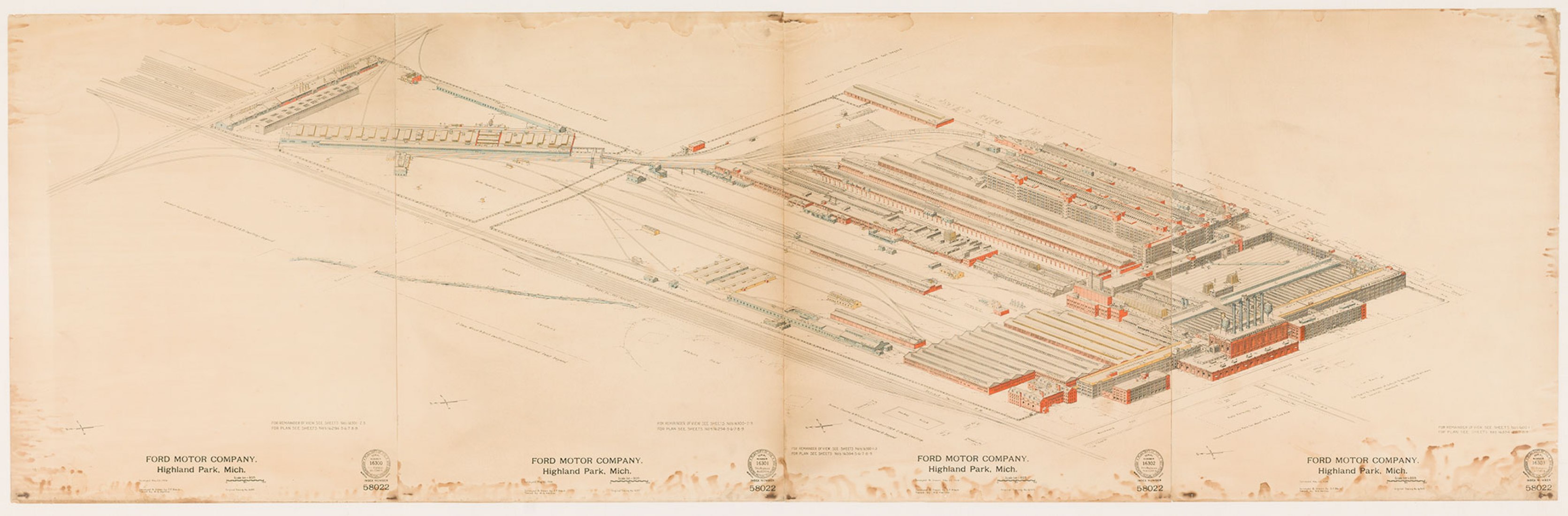

This room dedicated to the birth of the automobile traces the transition from the horseless carriage designed especially for the client to its mass production, a process that is part of the conception of movement developed at the end of the 19th century under the influence of new technologies. of photography and film. The shape of the car evolved from its early angular, box-like appearance to the sleek aerodynamic shapes it has today, achieved through the use of the wind tunnel. These streamlined shapes were anticipated by the work of artists and architects in the early decades of the 20th century, and in the automobile, they became the very symbol of modernity.

In its early days, the automobile saved the city from the stench, disease, and pollution caused by horse-drawn vehicles. However, in the current era of climate change, it has become the urban polluting villain.

However, electric power also had a dominant presence from the earliest days of motor racing. Included in this exhibition is a copy of the Porsche Phaeton, from 1900, which has electric motors in the wheel hubs, a concept that was considered revolutionary when it was included in the first NASA electric vehicle that traveled the surface of the Moon.

History has come full circle, as we are on the threshold of a new revolution in which electric propulsion goes hand in hand with "mobility as a service" -exemplified in mobile applications for traveling or car sharing-, to which the perspective of autonomous vehicles is added.

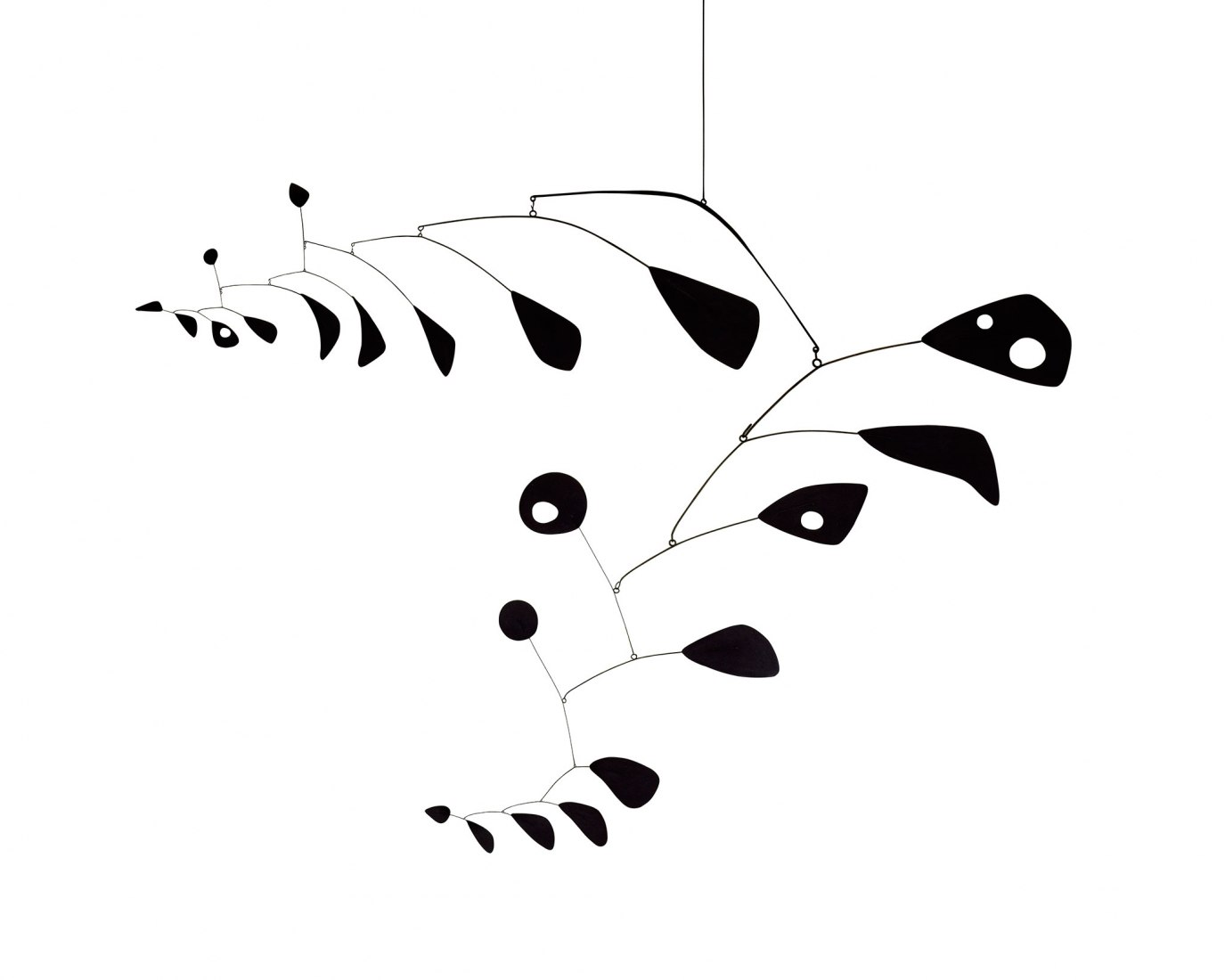

Alexander Calder. 31 Janvier, 1950.

Sculptures

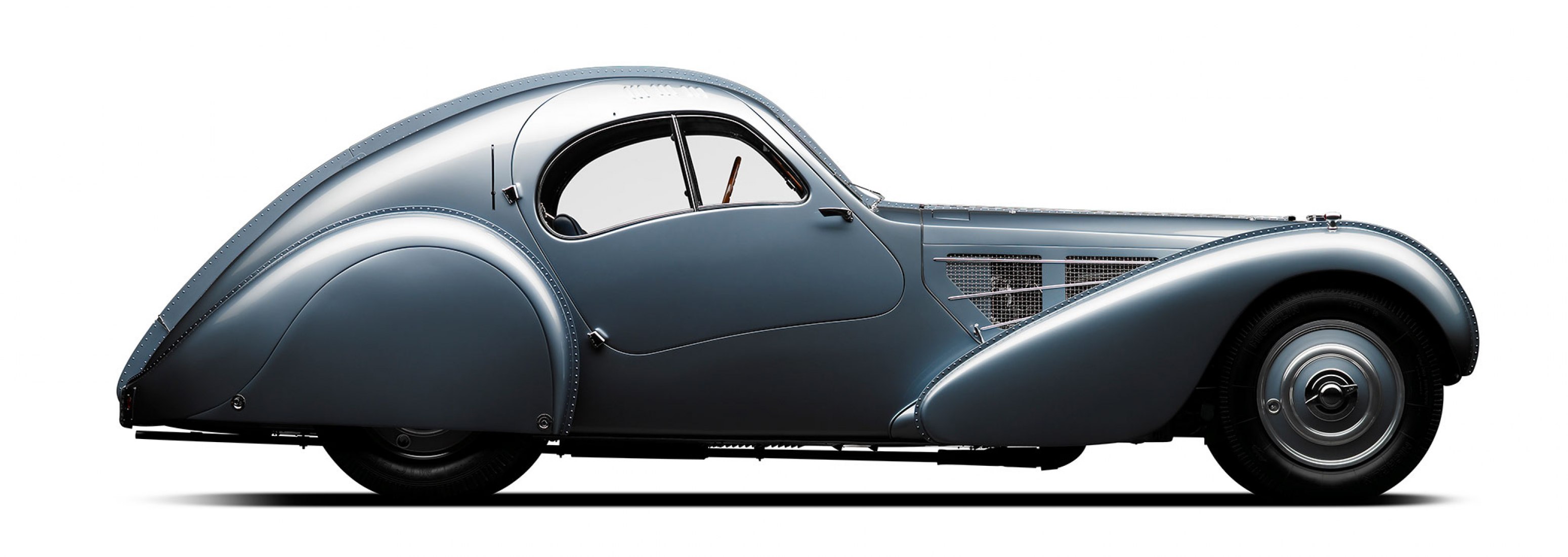

In the early 1950s, Arthur Drexler described automobiles as "empty sculptures on wheels." In this room, we reaffirm that statement, by juxtaposing four of the most beautiful automobiles of the 20th century with sculptures by two of the greatest artists of the same period: Reclining Figure, by Henry Moore, defined by its smooth curves; and the colossal mobile by Alexander Calder, January 31, which stands out for its incessant and fluid movement.

Each of these cars stands out for its technical excellence – two of them are considered the fastest production cars on the road – but here we celebrate the beauty of their flowing lines.

Like great works of art, the Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic, the Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia, and the Pegaso Z-102 Cúpula are of exceptional value as limited editions made for connoisseurs. Despite being mass-produced, the Bentley R-Type Continental also produced only about 200 examples. Another analogy between this work and that of the artist's studio is reflected in the bodies of these cars, molded one by one by artisans who manually bent the metal to create their compound curves.

The Atlantic, created by Jean Bugatti, was linked to a family immersed in the world of art and architecture for several generations. Next to the car, the sculpture Panther on the prowl, the work of Jean's uncle, the artist Rembrandt Bugatti, is presented here. Thus, you can see how both creations evoke movement.

Popularizing

This room shows the next step in the evolution of the automobile: attempts to produce a modern, reliable and affordable 'people's car' for everyone.The process began in the 1930s with the deployment of industries on a national scale, often tinged with political connotations. After World War II, during a period of economic recovery and shortages, the automobile became a symbol of regeneration and national pride.

The limitations of size, cost, and availability of materials imposed by post-war austerity did not diminish the creativity of the designers; On the contrary, they served as a spur to encourage innovation and ingenuity and to achieve more with less.

The art and fashion of the time merged with the appeal that mobility aroused in the masses. Examples of this trend include the Austin Mini and the Op Art mini skirt, as well as the logo that Victor Vasarely designed for Renault.

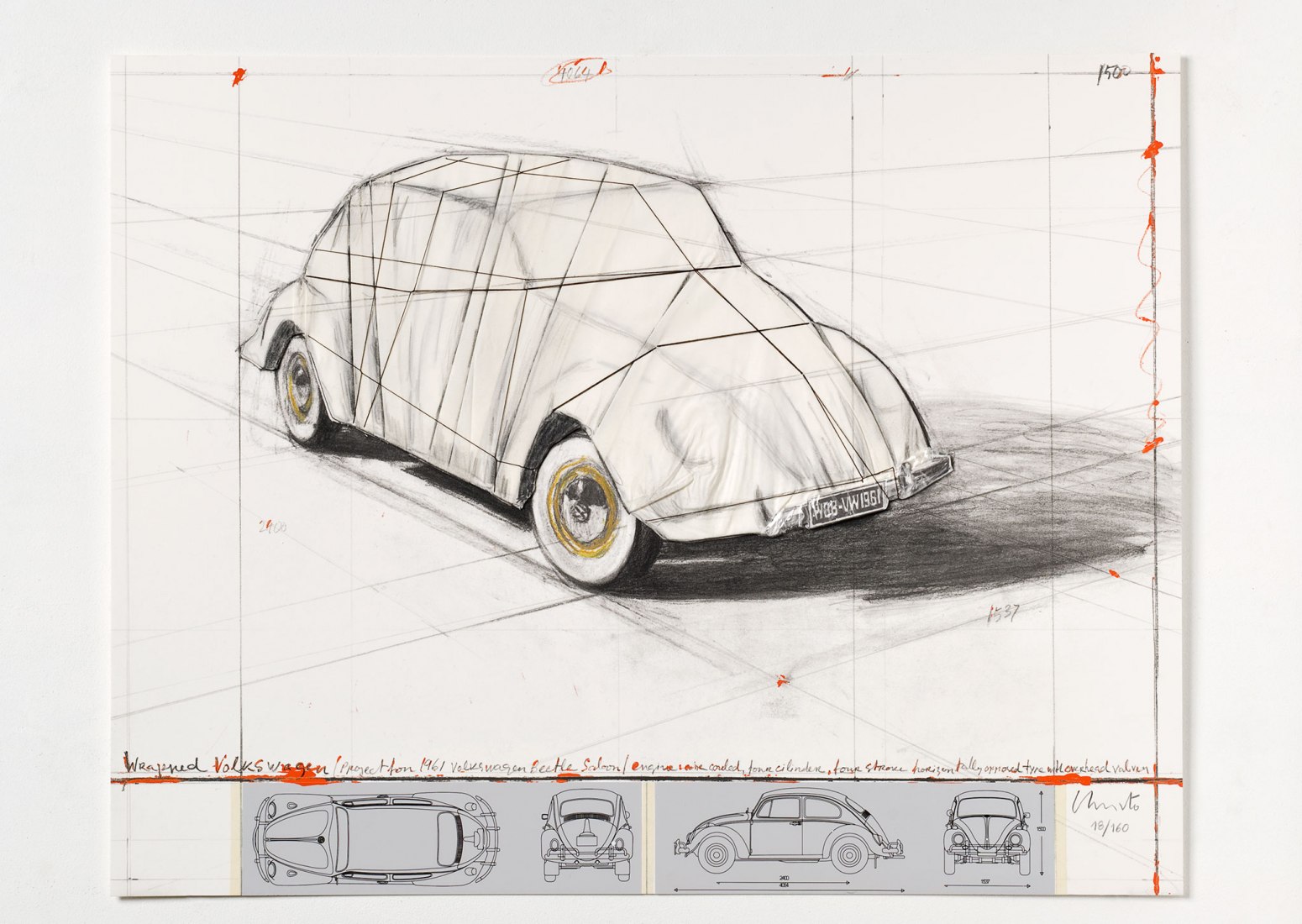

Some of the cars on display, such as the Beetle and the VW Microbus, are examples of the contribution made by companies such as Volkswagen to the democratization of the automobile. During that time, the proliferation of compact cars in Europe and their larger relatives in the US amplified the automobile's footprint on the urban and rural landscapes of both continents.

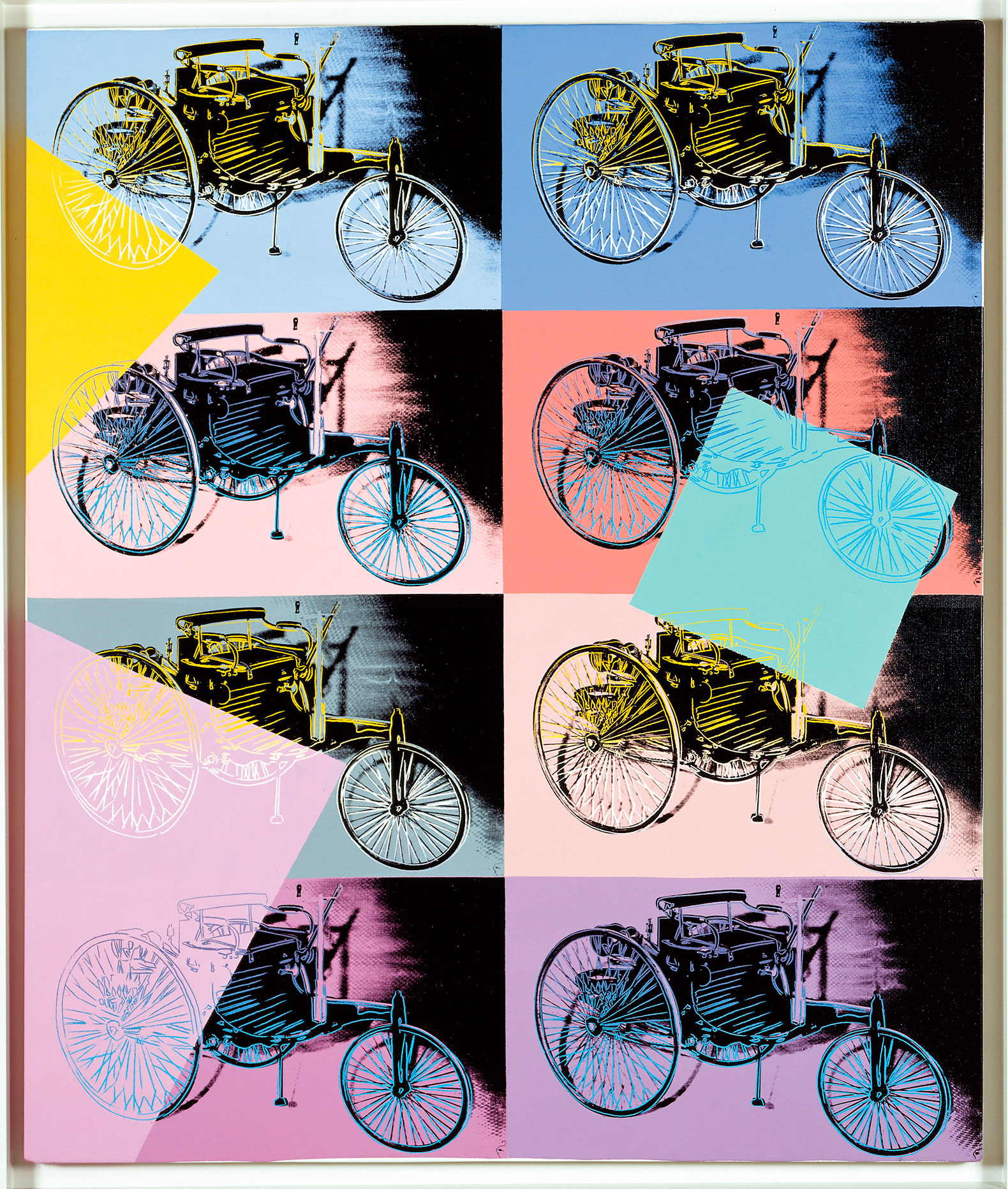

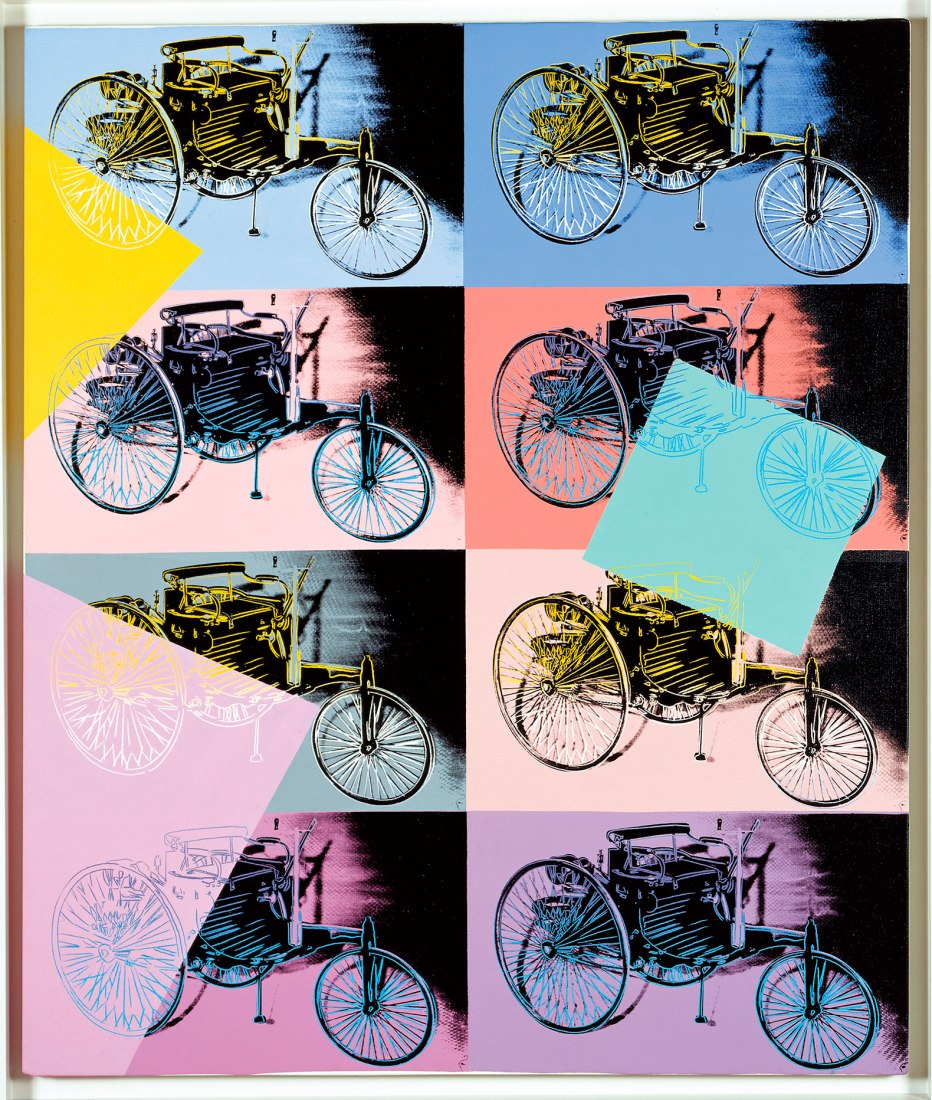

Andy Warhol. Benz Patent Motor Car (1886), 1986.

Sporting

During the post-war economic boom years of the 1950s and 1960s, the technical demands of racing, especially in Formula 1, meant that the design of "racing" and "road" cars was still separated. more, to become different disciplines. The market for high-speed "sports" cars expanded and manufacturers adopted the technology of their racing counterparts.

The five examples selected for the sample are, each in its own way, a delight to the eye, regardless of whether they were born as vehicles to race on the road or on a closed circuit. Art and fashion converge in their designs in order to satisfy the fantasy of speed and adventure; they are glamorous and desirable objects of contemporary culture. The most emblematic examples projected their powerful image on the big screen, rivaling the leading role of Hollywood stars.

These cars were portrayed as cult objects by artists like Andy Warhol and designers like Ken Adam. Throughout his life, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright hoarded more than eighty cars, many of the classic pieces included in this exhibition. The "Automobile Objective" here he showed, a project that he devised for Gordon Strong in 1925 and that was never built, constituted the first architectural use of a spiral ramp, an element that would later be key in his conception of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

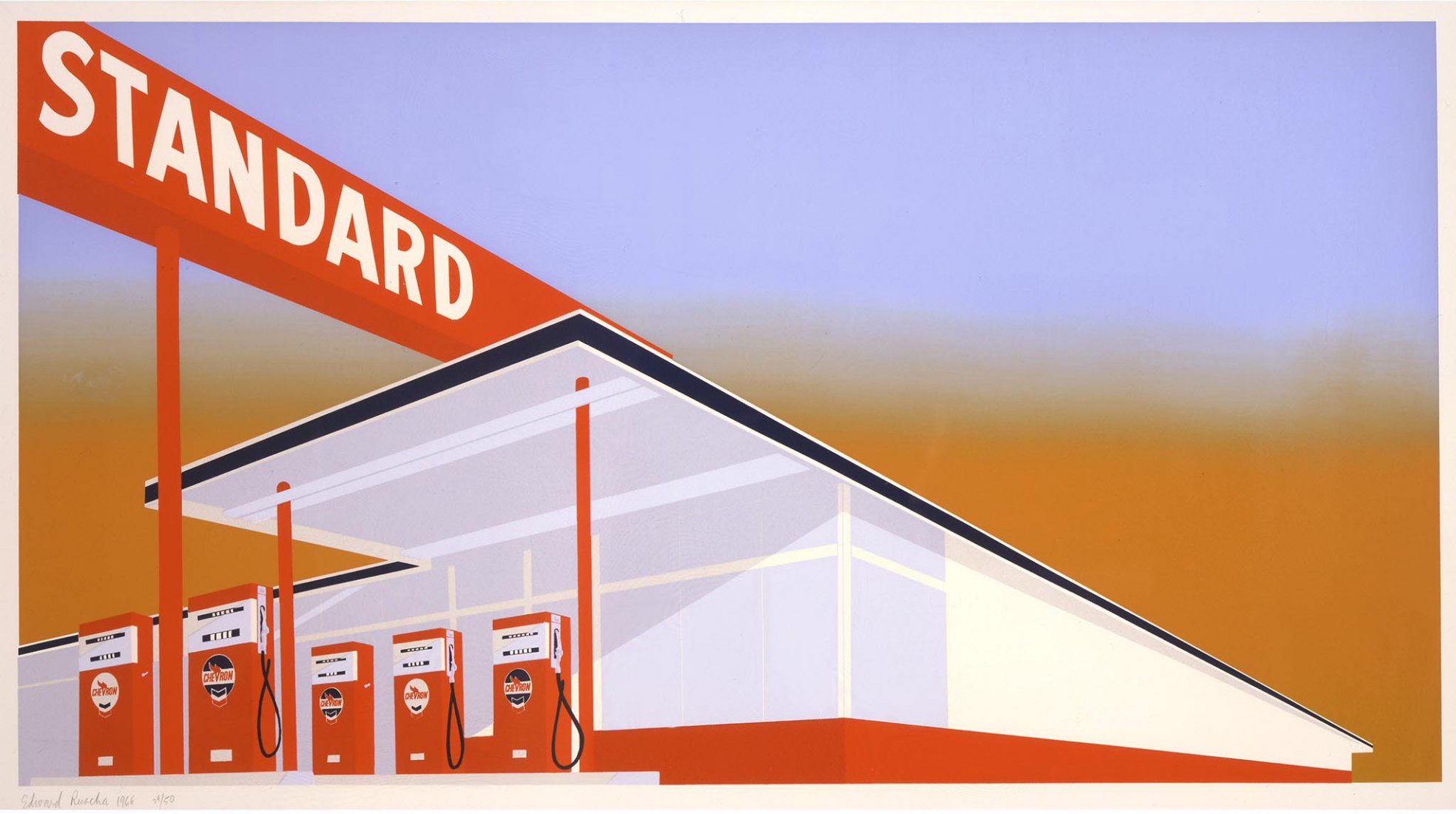

Edward Ruscha. Standard Station, 1966.

Visionaries

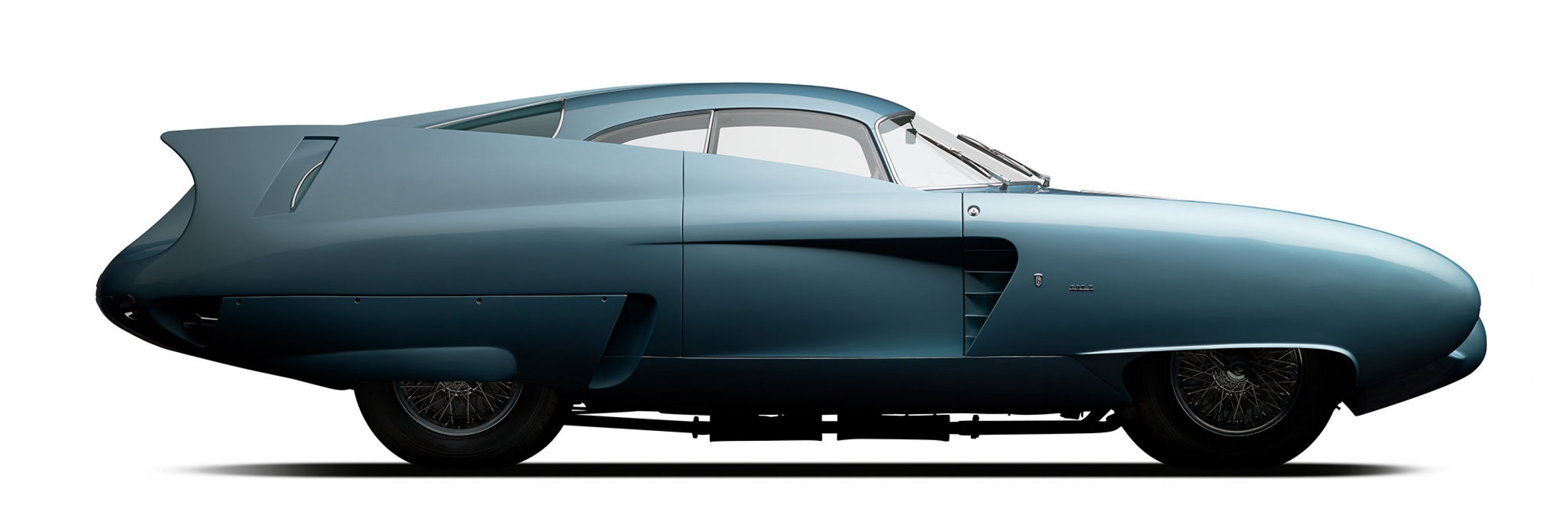

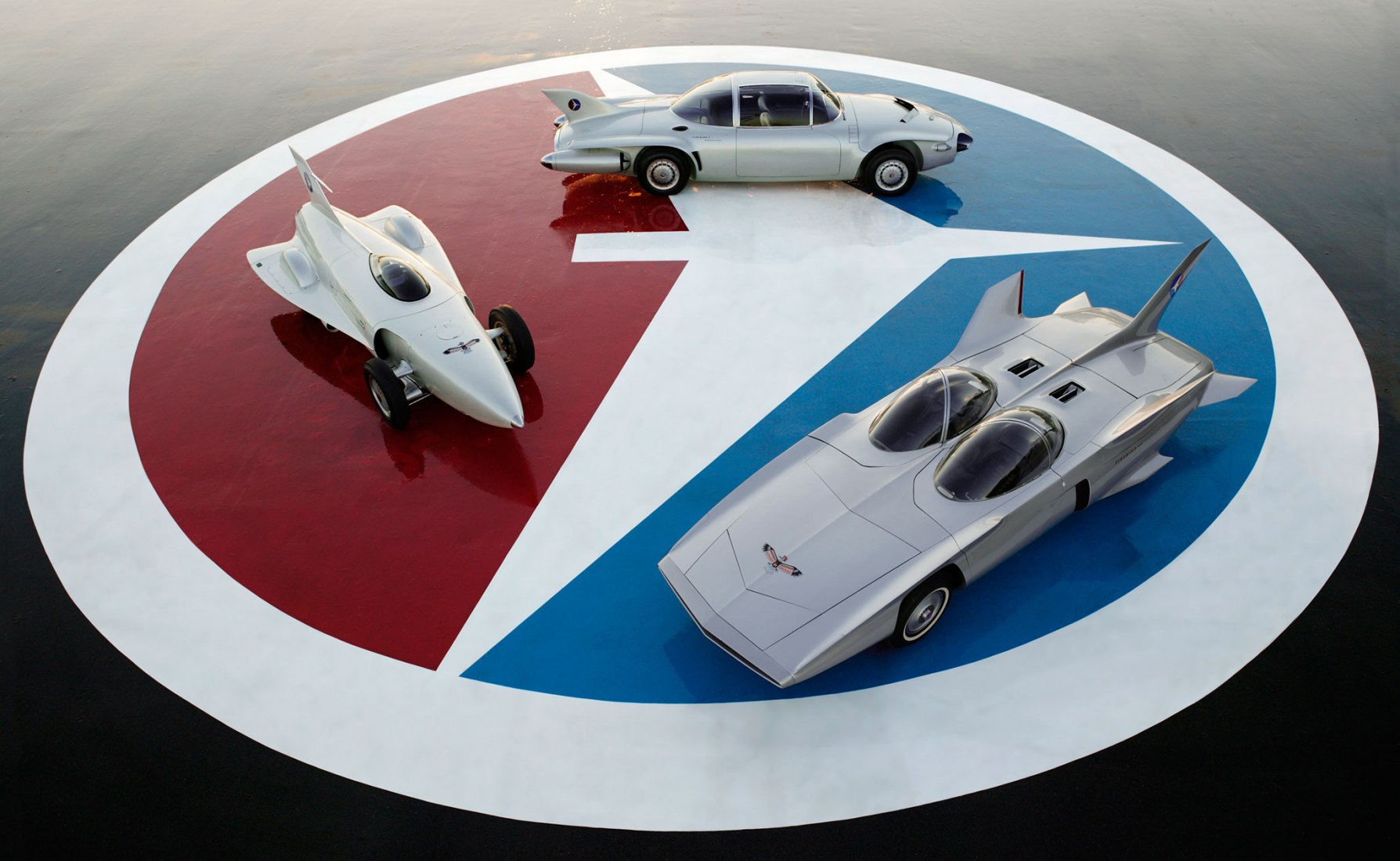

The Visionaries gallery begins in the middle of the 20th century, when the way had already been paved for the arrival of utopian vehicles, and artists and designers were launched to explore radically new forms related to speed and movement. Many anticipated the possibilities of the future of driving, decades ahead of their time. Cars, fueled by the desire to go even faster, pushed the boundaries of engine technology and aerodynamic shapes, under the impetus of new technologies in turbines, jet engines, nuclear power, and automation.

This space pays homage to a diverse set of visionary vehicles and their designers, extolling the beauty of flowing forms and their achievements in aerodynamics. The automobiles are exhibited alongside works from the Futurist movement—whose members are fascinated by movement and speed—including Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), whose bronze suit flows as if the figure was in a wind tunnel.

There are visual affinities between the futuristic paintings of Giacomo Balla and the cars made as unique prototypes, exemplified in the room by three General Motors models from the 1950s, which are on display together for the first time in Europe. In that decade, images of driverless cars were also conceived, then visions of science fiction, which today are very close to reality. The utopian vision of automotive design is reflected in the art and architecture of Eero Saarinen's modern masterpiece: the General Motors Technology Center, which has been defined as an "industrial Versailles".

American

Nowhere has the impact of the automobile been felt like in the U.S. The car has shaped its economy, its landscape, its urban and suburban spaces, and defined its popular culture to a degree not known anywhere else in the world. . The US was the first country to realize the benefits of mass use of private cars and the first to have to deal with the environmental consequences of a car-based society that suffers from social isolation and exhaustion caused by driving. and come daily from home to work and from work to home.

The romance of the road, the journey through the continent's vast open spaces and endless horizon, is emblematic of American culture, with its traditional roadside diners and gas stations. The road trip has featured photographs, paintings, music, and literary treatises from the New Deal of the 1930s to the present. In this room, we can look through the camera lens at Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott, and O. Winston Link, as well as paintings by Ed Ruscha and Robert Indiana. As a backdrop to the vehicles, you can see the contrast between the precision of a Donald Judd sculpture and the crushed automotive remnants of a John Chamberlain work.

The wide range of vehicles exhibited here highlights the contrasts between a gigantic luxury sedan with extravagant rear fins, a typical high-powered sports car, a brightly colored tuned racing car, and a Jeep designed for war and characterized by its bare-bones functionality...

Future

The last part of the exhibition is dedicated to the work of a young generation of students, who have been invited to imagine what mobility will be like at the end of this century, a date that will coincide with the bicentenary of the birth of the automobile. This completes the circle of the exhibition itinerary, tackling the same difficulties that the inventors of the car faced more than a hundred years ago: urban congestion, scarcity of resources, and pollution — all of which are currently exacerbated by climate change. —, which are now presented in a projection of the future.

The sixteen selected international schools of design and architecture, from four continents, have been given complete freedom to share their visions for the future of mobility. Their proposals are shown in this room through models, audiovisuals, renderings, drawings, and writings, which reflect the collaboration that has existed between students and various members of the industry, designers, artists, and architects.

Clay Modeling Studio

This section of a modeling shop illustrates the production of life-size clay models, a process devised in the 1930s by legendary General Motors chief designer Harley Earl. Despite advances in computer technology and virtual reality, this tradition continues to survive in the industry. General Motors' Cadillac brand has made it possible for this LYRIC EV clay modeling studio replica to be experienced live from the show. There are parallels with artists' studios, both in the past and today.

Model cars

This space shows how the cultural importance of the automobile extends beyond the vehicles themselves to encompass the world of toys and models. Thanks to the Hans-Peter Porsche Traumwerk Collection, a fascinating selection of artefacts from a time when mechanical objects were particularly appreciated is presented here. Complementing them, various scale model car replicas exhibit the same craftsmanship that can be found in miniature paintings and figurines or jewelry pieces.

![Frank Lloyd Wright.Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium (unbuilt), Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland], 1924–25. Perspective. Colored pencil on tracing paper. 50.8 x 78.7 cm. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives. The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine. Arts Library, Columbia University, New York. 2022 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona. Photograph by Frank Lloyd Wright. Frank Lloyd Wright.Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium (unbuilt), Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland], 1924–25. Perspective. Colored pencil on tracing paper. 50.8 x 78.7 cm. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives. The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine. Arts Library, Columbia University, New York. 2022 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona. Photograph by Frank Lloyd Wright.](/sites/default/files/styles/mopis_news_carousel_item_desktop/public/metalocus_foster-fond_motion-autos-art-and-architecture_22.jpg?itok=IuHFo-76)