We know this project from 1927 only by a model and a few drawings, as it was never actually built. In fact, we do not have any evidence that Baker and Loos ever got to meet each other, let alone that Baker even knew of the existence of this project dedicated to her.

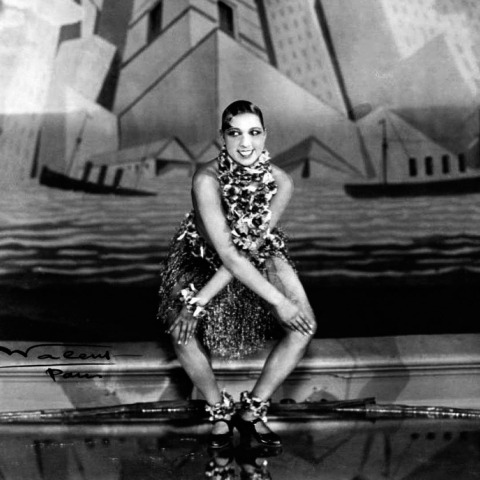

The American cabaret dancer Joséphine Baker arrived to Paris in the 1920s. Her sensuality and savage moves on the stage soon got her into the Thêatre des Champs-Elysées. She used to perform an imitation of the African dances, wearing nothing more than her famous banana skirt. Her exoticism captivated the European public, as well as the Austro-Hungarian architect Adolf Loos, who was at the time working on the house for Tristan Tzara in Paris. He started to design a house of a complex spatial distribution that was seldom mentioned in the following years.

It consists in the transformation and union of two existing houses on a corner. As we crossed the entrance, we would find a huge staircase, maybe a potential stage for a cabaret show with a single spectator, Adolf Loos. The hall and the living room are on the first floor. Adjacent to the latter is a smaller living room, and a secret corner to read in private. The sequence continues through a smaller staircase that takes us to the second floor, where we would find the dining room, somewhat isolated from the rest of the spaces in the house. We could say it is a distribution of pleasure, that recreates the sequence of an evening in good company. But the most important space of the house is at its center: the swimming pool. Lit by zenith light, it has the peculiarity of being perforated by a series of windows that connect the pool with the living room. Observing Joséphine’s body, with her dark, glowing and flawless skin moving naked in the water flooded in light, was an experience that, to Loos, justified the construction of this giant fish tank.

This act of voyeurism is quite surprising, as Adolf Loos defined the window as something that “lets in the light, not the gaze”. However, there is a more controversial tension between this project and Loos’ firm architectural beliefs. The Baker House would have a solid exterior aspect, with small windows, and would be cladded in marble pieces forming a black and white stripes pattern, with no apparent function except ornament. But we know from Loos’ writing “Ornament and Crime” (1908) that to him, the evolution of culture implied the abandonment of ornament in every object of daily use, and in fact he skillfully applied this motto during his entire career. The famous text despises decorative arts, and even claims that the modern man who tattoos his skin is “a criminal or a degenerate”. Why then wrap the house in these lines that look almost like tattoos?

There has been a lot of speculation around this question. The most consistent theory is the one which refers to Adolf Loos’ thoughts on the origins of primitive art, more particularly the cross on the cave walls:

“A horizontal line: the reclining woman. A vertical line: the man who penetrates her”.

In other words, art started as an erotic impulse. The architect expresses his desire to be the vertical element that completes horizontal Joséphine. In fact, the whole house comprises some kind of fantastic mechanism that allows Loos to trap the dancer, hide her from everyone else’s gaze, take pleasure observing her from different points and finally possess her. Of course, all of this never actually happened, it remained a fantasy.

By the way, we don’t know if Loos met Joséphine Baker, but we do have the certainty that Le Corbusier did (and probably knew her quite well).They met at a cruise returning from South America, and that trip resulted in a bunch of sketches of her, dressed and nude. The architect later included them in his book “Precisions on the Present State of Architecture and City Planning” (1930), and used them to talk about concave and convex curves. But that is another story…