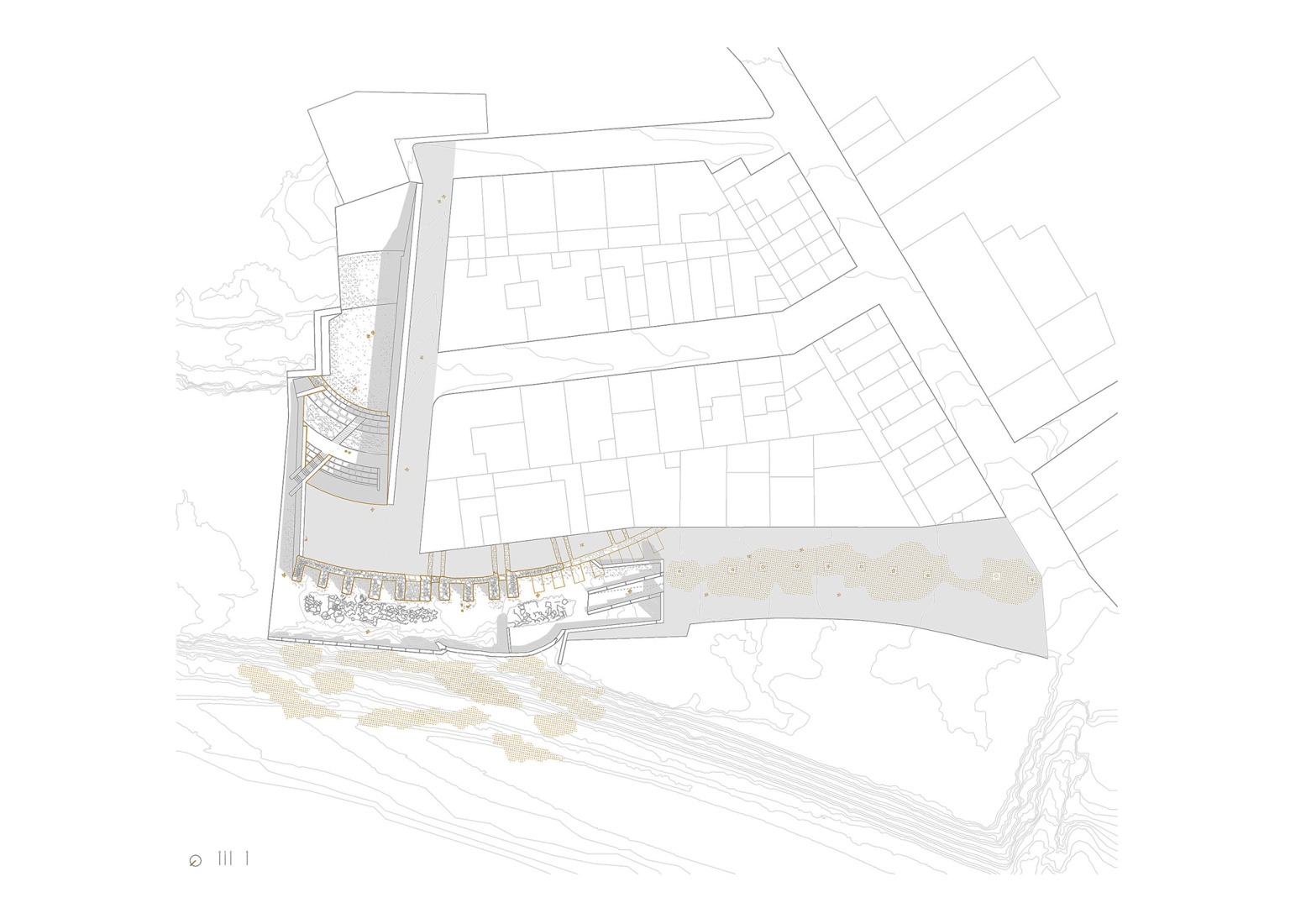

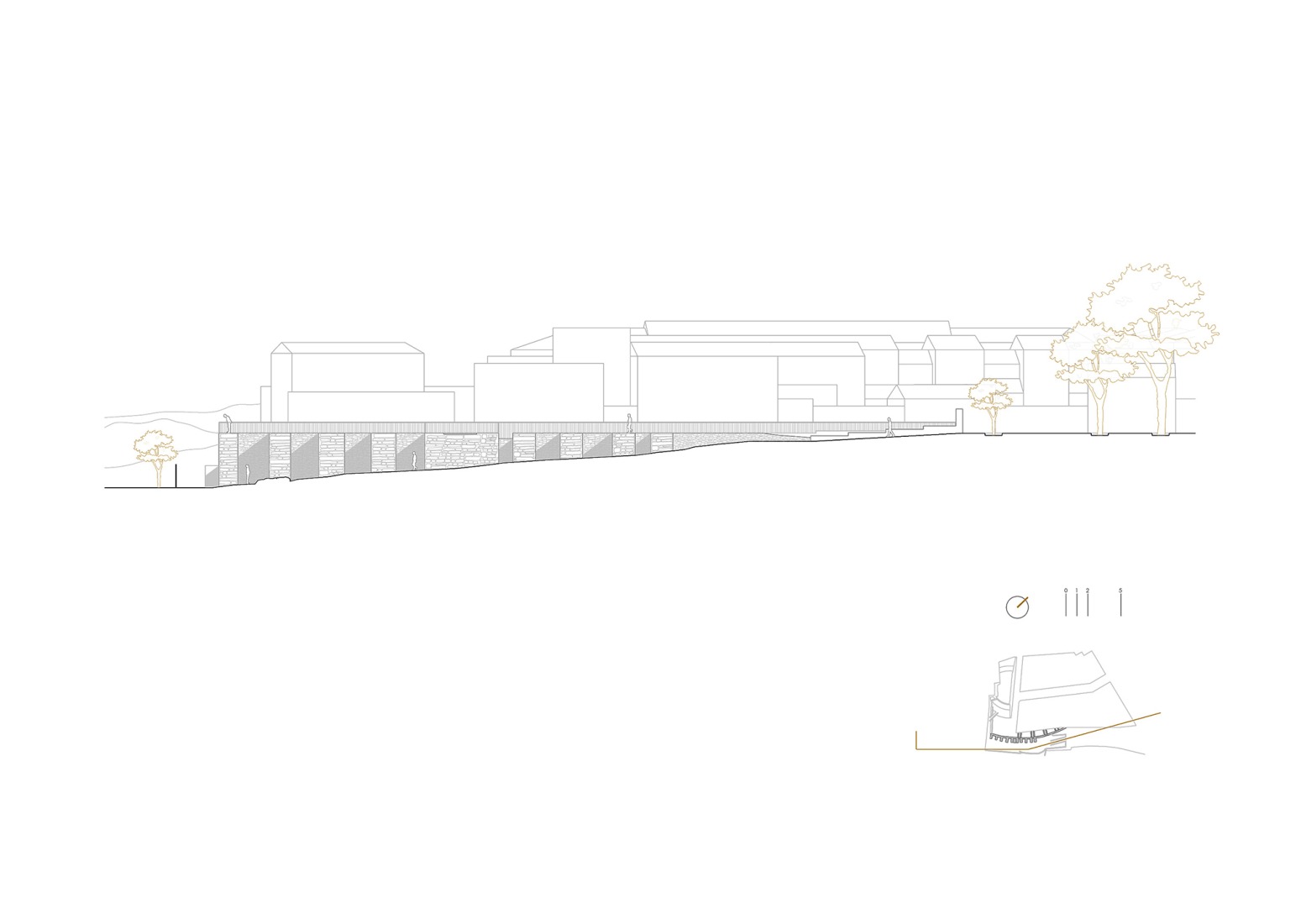

The architectural, morphological, and structural analysis by Pablo Millán, which incorporates archaeological and urban planning criteria, has enabled the creation of a planimetric survey, the preparation of elevations, and the stratigraphic analysis of the walls. The project's research has confirmed that the amphitheater, with its elliptical plan, was a complex infrastructure located outside the walls of the Roman urban fabric, as was typical for such structures. Its dimensions and materials—the local golden calcarenite stone—have highlighted the significance of the discovered remains.

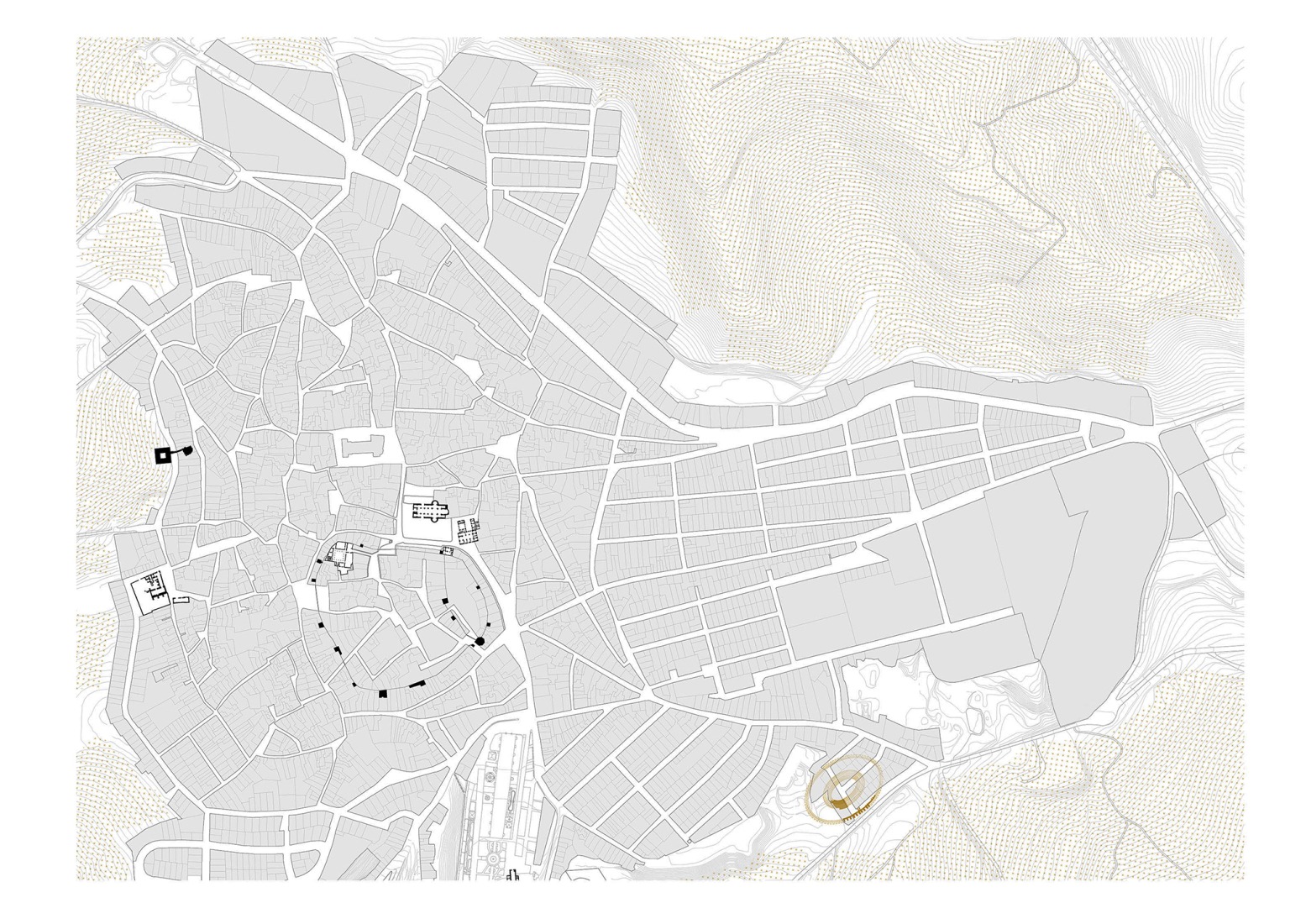

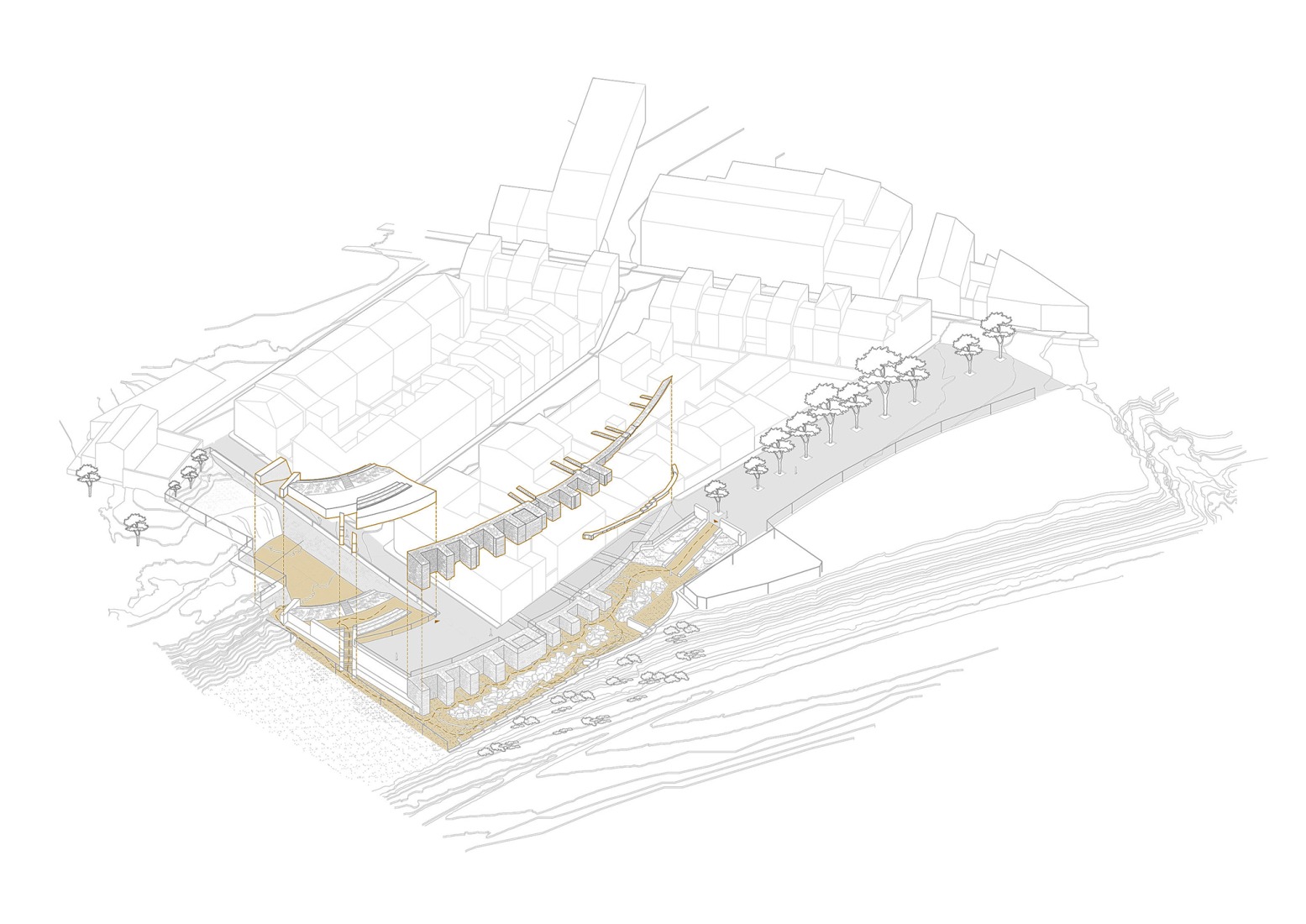

With social, functional, and symbolic implications, the location chosen for the Obulco Amphitheater responds, on the one hand, to urban planning and topographical factors, but is also associated with strategies for representing power: large architectural structures dedicated to public spectacles were erected as symbols of Romanization and municipal prestige. In this sense, the carefully considered intervention highlights the memory linked to this void and attempts not only to preserve the ruins but also to integrate them into the contemporary public space.

Rehabilitation and enhancement of the Roman Amphitheater of Obulco by Pablo Manuel Millán Millán. Photography by Javier Callejas Sevilla.

Project description by Pablo Manuel Millán Millán

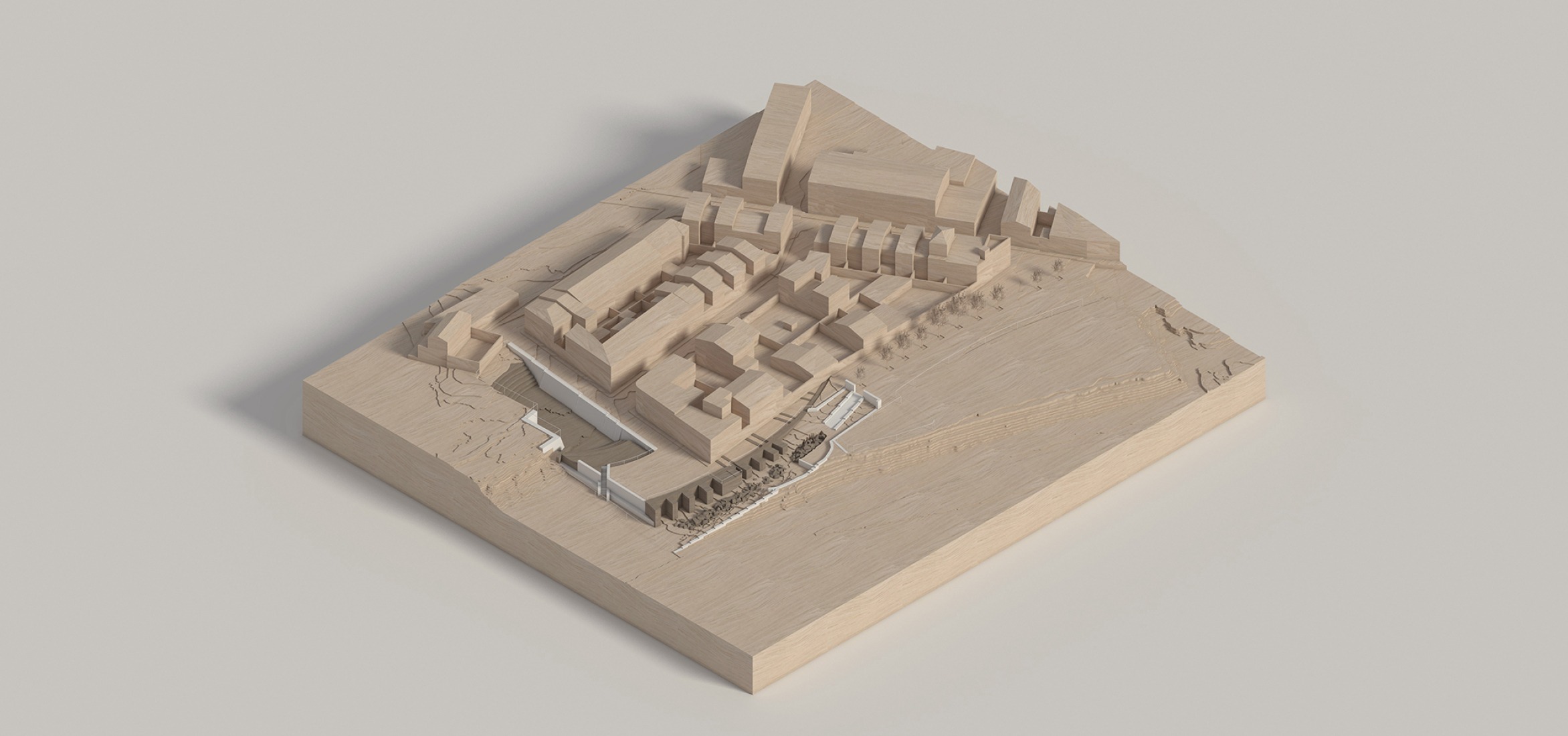

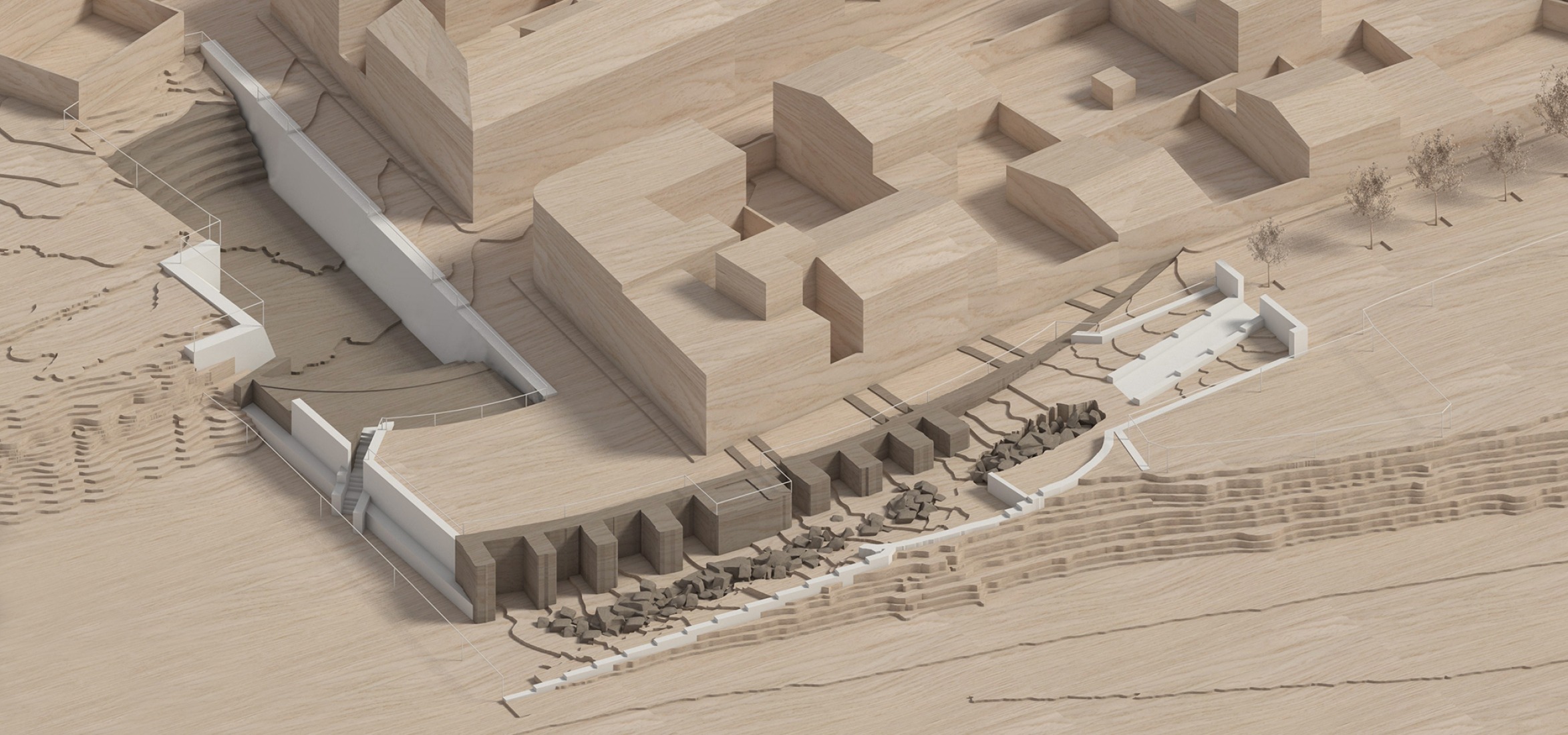

The discovery of the Roman Amphitheater of Obulco in Porcuna (Jaén) represents a milestone for heritage architecture in Andalusia. What began as a preventative intervention on a plot of land on the urban periphery led, after the initial cleaning phases, to the identification of an imposing ashlar structure that has proven to be a substantial part of the southern façade of a Roman amphitheater. The formal and constructive characteristics of the building reveal a large-scale public structure, capable of accommodating more than 10,000 spectators. It belongs to the type of amphitheater with an elliptical plan, perimeter walls articulated by pillars and openings, and cyclopean ashlar masonry with rusticated walls.

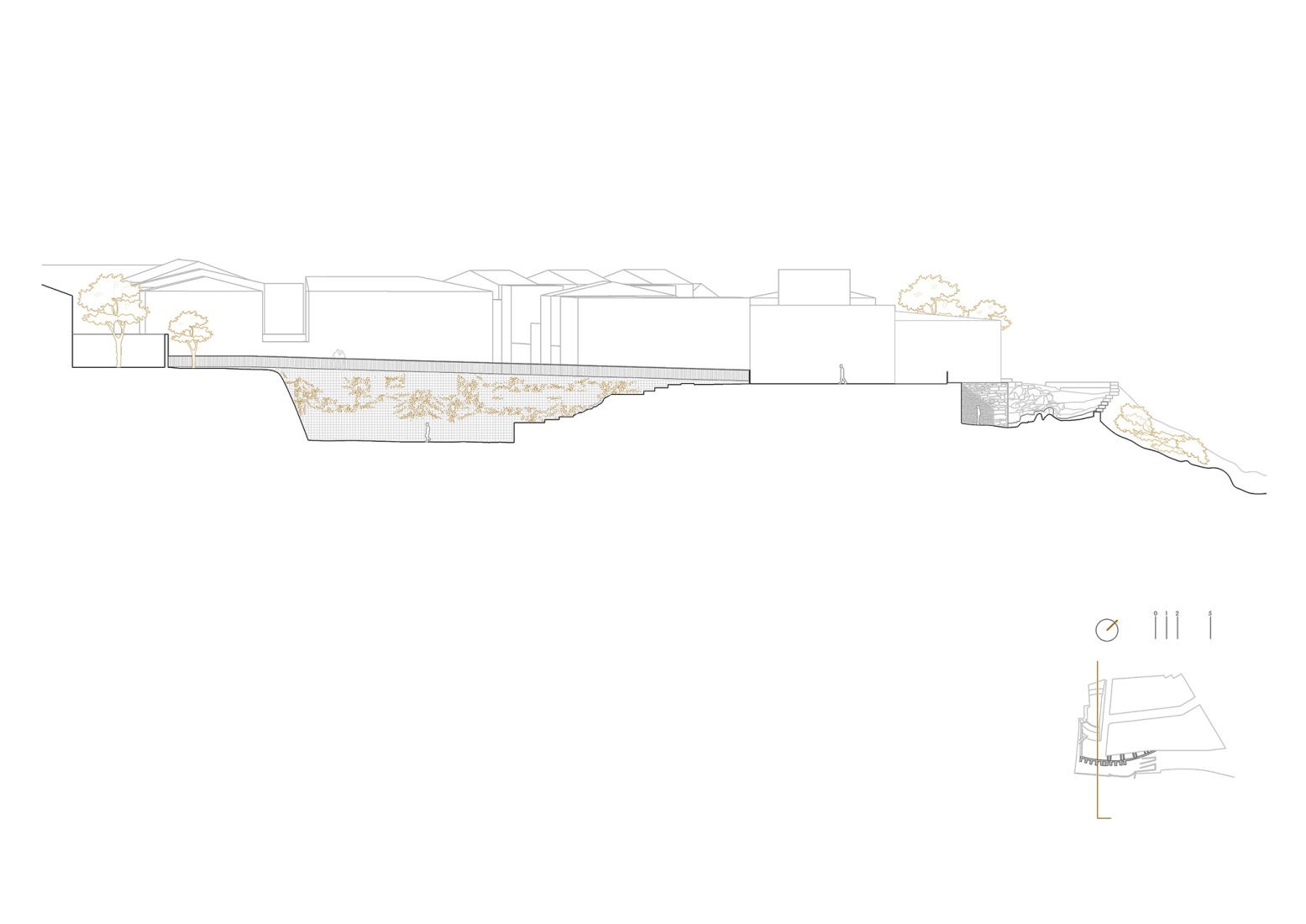

From an architectural perspective, this type of building follows a model imported from Rome, adapted to local conditions through hybrid technical solutions. These solutions combine the use of the natural topography—in this case, a slope existing to the south of the ancient city—with massive structures. The identification of the masonry style, the interlocking techniques used to join the ashlar blocks, the rhythmic façade design with its alternating solid and void sections, and the dry-stone masonry in some areas, all point to a construction that, based on its formal language and technical execution, can be dated to around the 1st century AD, during the Julio-Claudian period.

Heritage architecture has played an essential role in this intervention. Beyond descriptive archaeology, morphological and structural analysis has allowed for the reconstruction not only of the building's original form but also of its structural and spatial logic. The planimetric survey, the documentation of the elevations, and the stratigraphic analysis of the walls have been approached using an architectural methodology, integrating archaeological and urban planning criteria. These tools allow us to interpret the building not as an isolated ruin but as a complex infrastructure integrated into the Roman urban fabric, with social, functional, and symbolic implications.

The Obulco Amphitheater is located outside the walls of the original town center, as is typical for this type of construction. Its location reflects urban planning and topographical factors, but also strategies for representing power: these large buildings, dedicated to public spectacles, stood as symbols of Romanization and municipal prestige. The choice of site, the monumental scale, and the richness of its materials—especially the local golden-hued calcarenite, worked into large, rusticated blocks—reinforce this symbolic dimension of the architecture.

It is significant that the discovery occurred in an area of recent urban expansion, highlighting the need to develop heritage protection policies that consider both the subsoil and the historical layers of the territory. In this sense, the role of architecture as a design discipline also becomes relevant. The intervention not only seeks to preserve the remains but also to integrate them into the contemporary public space. This requires a technical approach that combines conservation, historical analysis, and urban design, enabling the coexistence of heritage values with the daily life of the municipality.

From a disciplinary perspective, architecture emerges here as a fundamental tool for the interpretation and management of heritage. Its capacity to analyze structures, design integrated solutions, and generate spatial discourse allows for a broader understanding of these remains beyond the archaeological object itself. The amphitheater is not merely a vestige, but an urban operation that articulated flows, collective rituals, and social hierarchies. Reconstructing its form and function is, ultimately, reconstructing a substantial part of Obulco's urban imaginary.

The inclusion of this area within the declaration as a Site of Cultural Interest in the category of Archaeological Zone reinforces the need to approach these remains from a multidisciplinary perspective that includes archaeology, urban planning, art history, and architecture. The aim is to design intervention strategies that not only document the findings but also allow for their interpretation, active conservation, and public dissemination. The challenge is to project a new layer of meaning onto these vestiges, where heritage is not reduced to a frozen image, but is incorporated as part of the living fabric of the city.