This twenty years were probably the ones most marked by the architect's pictorial production and this, inevitably, was accompanying his turn from the first works of rationalist dyes or his different brutalisms in the sixties, towards buildings of an absolute postmodernity, as if each new work were one of his paintings raised in three dimensions.

The references that Testa himself recognized in its beginnings (Le Corbusier, Wright, Van der Rohe), are now Graves or Tschumi, contemporary architects of the Argentine Master, who were synchronously doing some of their most recognized works on the other side of the world.

“A young man now has to be in the year 2011. Architecture and painting are always global things. In 1500 or 1600 Argentina was baroque, and Italy too. You recognize the difference between them in the same period, but both are baroque. The fundamental thing is to be in the time in which you live."

Clorindo Testa, 2011.1

This change in Testa's approach to the project is evident in almost all the works of this period, where it can be clearly seen how, with the passing of the years, the restrictions that marked it at some point, begun to dissolve and even to disappear completely. Let's say that even maintaining the architectural thinking processes that characterized it, this stage was distinguished for having almost absolute freedom regarding the built space, leaving it to be without dogmatic conditions, so typical of the discipline.

Recoleta Cultural Center (1979-1980). Buenos Aires Design (1990-1993)

In this case, we took the liberty of articulating these two works, which even with different clients and temporalities, share architect and land, so it would not be appropriate to analyze them independently.

The Recoleta Cultural Center, on the one hand, is the first work of this entire series in which Testa intervenes on pre-existing constructions, and does so on nothing more and nothing less than on an iconic assembly of buildings that go from the 18th to the 20th century, located between the Recoleta Cemetery and the Plaza Francia by landscaper Carlos Thays.

Started in the middle of the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional (the last of the many dictatorships that the South American country has gone through), the work is the result of a contest won by the team of Clorindo Testa, Jacques Bedel and Luis Benedit.

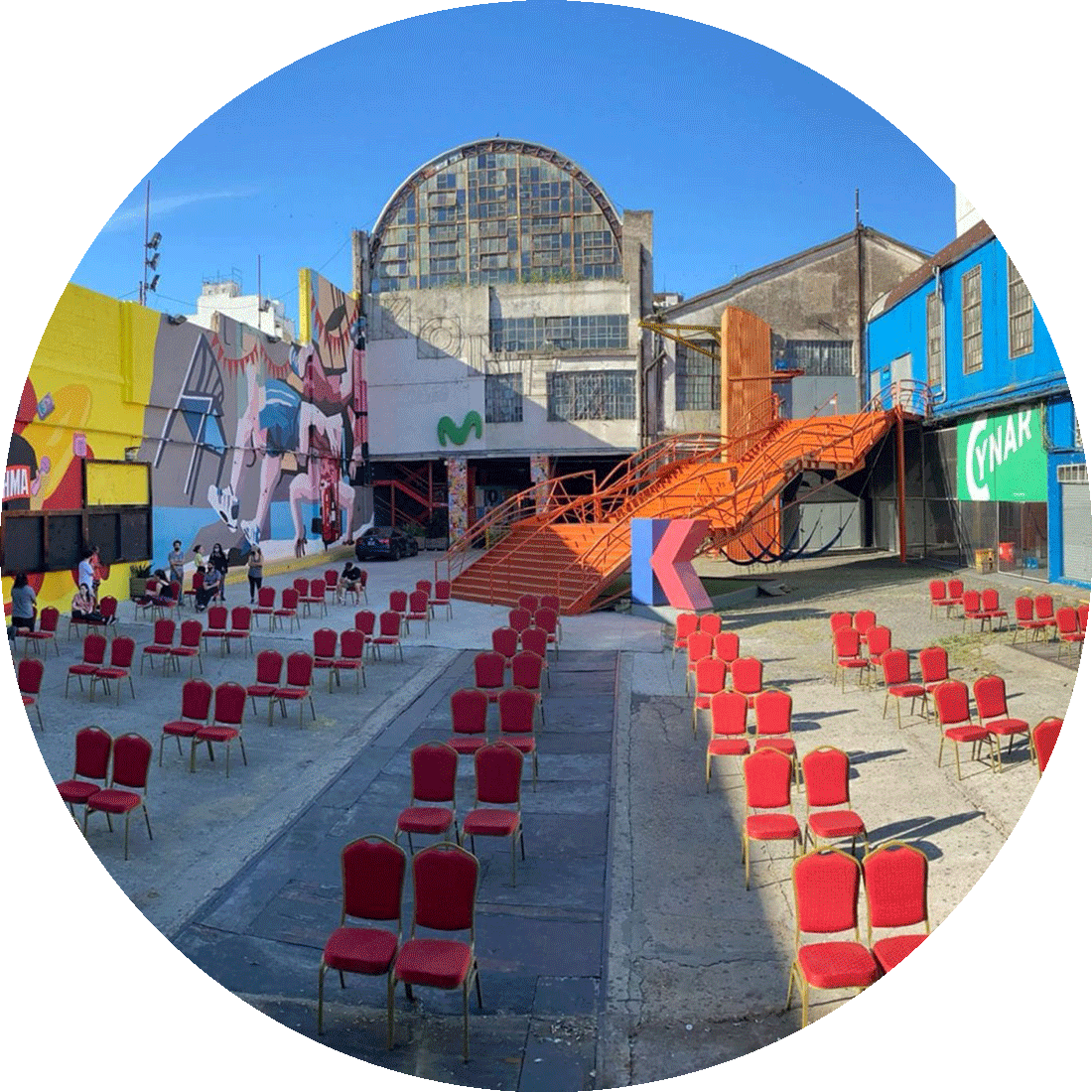

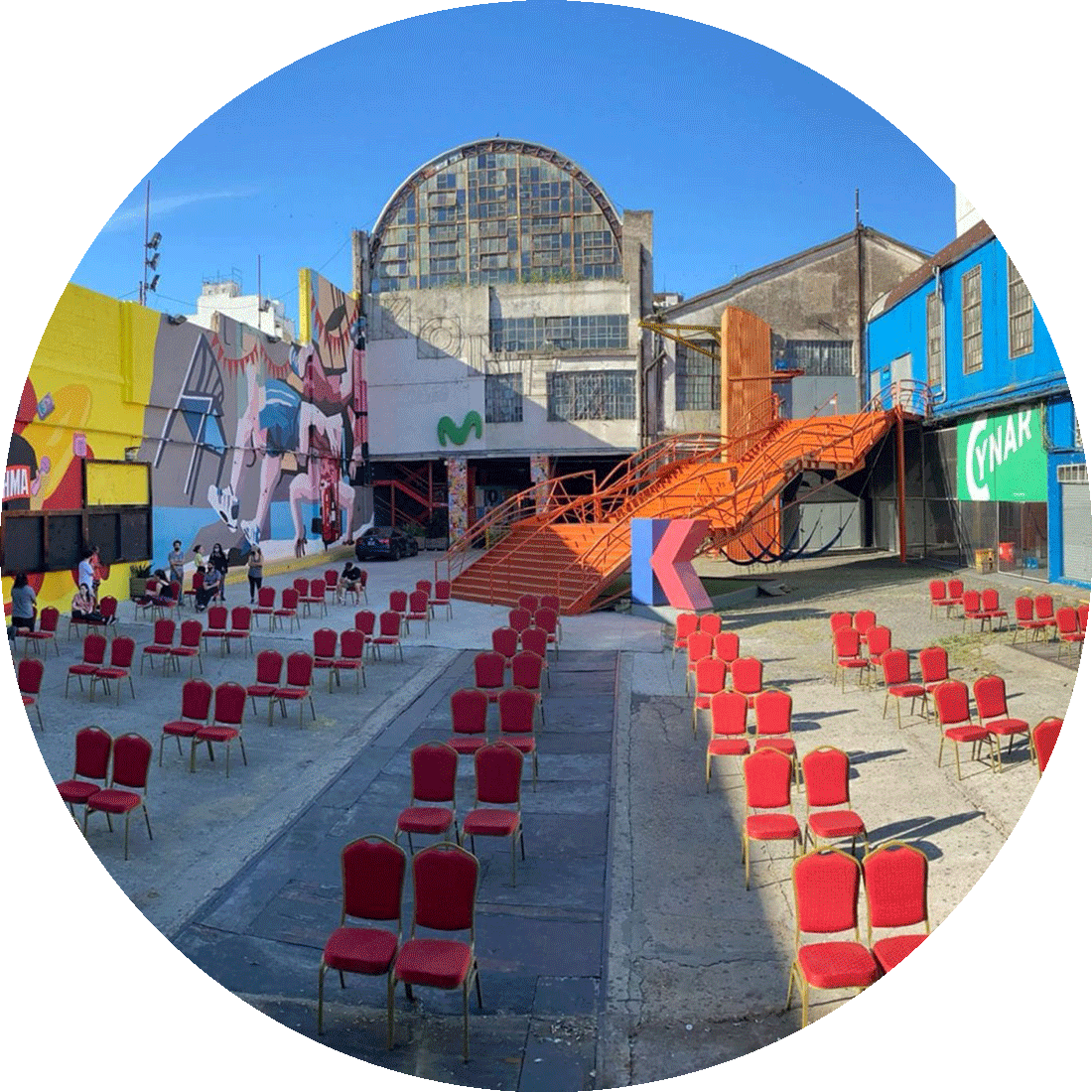

Recoleta Cultural Center + Buenos Aires Design by Clorindo Testa, Jacques Bedel and Luis Benedit. Photograph by © Delfina Cocciardi [Wikimedia] Under License CC BY-SA 4.0

The proposal consisted, in general terms, in structuring all these pre-existences (an old Franciscan convent organized in cloisters around five successive courtyards, the terrace, the Iglesia del Pilar in neo-Gothic style and the eclectic pavilions designed by Buschiazzo between 1880 and 1900) in a coherent route and, while preserving the line that delimited the complex, unifying its more than 10,000 square meters under the same stylistic and compositional criteria.

The Buenos Aires Design, designed ten years later, is located within the premises of the cultural centre and continues with the interventions that had been done previously. In this case, as part of the survey work, an old concrete berm and some precast beams were discovered that, as a whole, would become part of the Paseo de la Recoleta. A space exclusively dedicated to flâneur, located in which at the time became the most important design centre in all of Latin America, and which later became a sort of leitmotif of Testa's late work (Paseo de las Aguas, Balneario de La Perla, Konek Cultural City).

Both works are characterized by the use of important contrasts in all their aspects. From the new materials compared to the existing ones to the vivid colours that were used for both its interiors and exteriors (in this case part of the old buildings were also painted).

Casa Capotesta (1983-1985) Casa La Tumbona (1986-1989)

From the late 70s until well into the 2000s, Clorindo Testa dedicated part of his professional time to the realization of private homes (including his own), moving at times from public programs. These houses, for the most part, are part of a series in which the architect dedicated himself to investigate the possibilities and expressions of the cube.

The Capotesta house, designed for himself, is located right on the dune that defines the limit between the beach area of the city of Pinamar, and the area where the urban plot begins.

Although some debt to Neoplasticism could perhaps be recognized in the work, maybe due to the choice and distribution of colours, its character is frankly postmodern from several aspects. From the expressiveness of the built volume to the composition by means of fragments where, as he had already suggested in previous works, the almost arbitrary partitions and extensions that break the trihedron are seen again.

La Tumbona house by Clorindo Testa. Photograph by Mariano Imperial

This work also responds to that freedom that we mentioned previously. The architect himself pointed out that much of the work was empirical, both in project and construction, with resolutions that were born based on trial and error in work, painting and repainting with different shades, or adding parts that the house was asking with the passing of time.

La Tumbona, on the other hand, although it continues with the logic of the exploration of the cube, could be seen as the final evolution of that explosion of the solid where the house loses almost all the reminiscences of norms or guidelines that were left in the previous work.

In the Capotesta, for example, there was still logic in the destruction of the cube, with a terraced composition that responded to a playful use and to the views that could be obtained from the sea. In this case, although it is evident that there is an a priori definition of the project, the deconstruction of the volume is defined from the frankest compositional arbitrariness, which decants for one of the most important examples of Argentina's most sui generis postmodernity.

Konex Cultural City (2003-2005)

Finally, one of the last works by Clorindo Testa, designed as part of a National Contest of Ideas and Preliminary Projects organized by the Konex Foundation in 2003. The winning proposal had to recycle a series of warehouses from the old Konex printing house into a new cultural complex for the Abasto neighbourhood in the city of Buenos Aires.

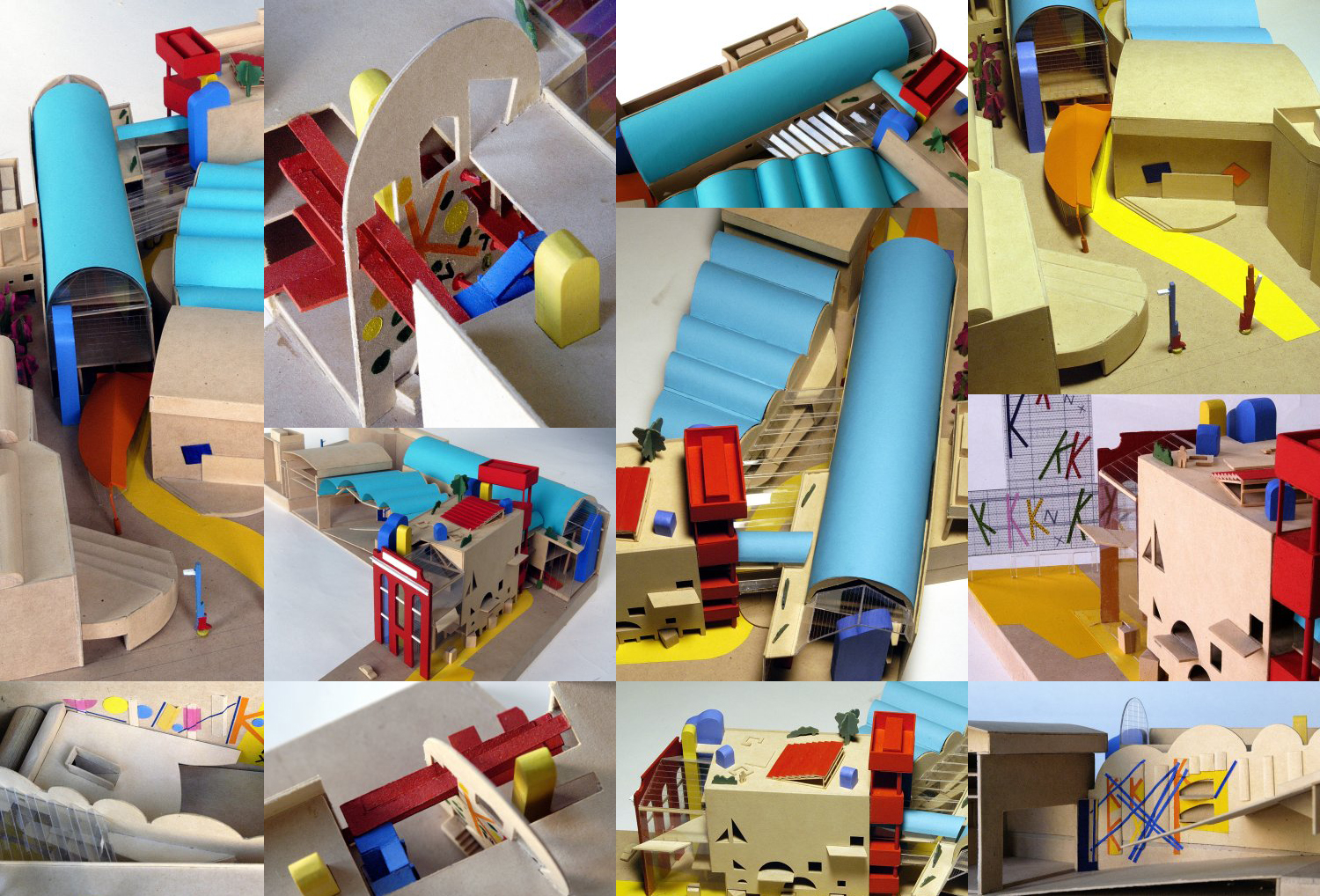

As he had already done in Recoleta, Testa and his colleagues (Juan Fontana y Oscar Lorenti) proposed an intervention that condensed a number of aspects that defined his work in the immediately preceding decades. On the one hand, the connection of all the pre-existing volumes conceptually unified but preserving the identity of each one of them as an independent part. This highlights another key, and now traditional, aspect of his work: the heterotopia installed in the project as a reflection of the very fragmentation of the construction of cities.

It is precisely this dialogic relationship between fragmentary architecture and the conceptual unification of space that Testa chooses to tie, again, through the resource of the discursiveness of the path that builds the internal journey through the Cultural City.

Formally, the work draws attention due to the exchange of shapes and colours that appear between pre-existing volumes, juxtaposing with the internal spaces, but, above all, due to the imposing orange exterior staircase, which at times acts as a circulation, by others as stands for the events that are organized in the courtyard, and even at times it becomes a colossal sculpture with total autonomy against the limits of the manufacturing environment.

Clorindo Testa's work is really fluctuating over time, zigzagging between different explorations without fear of what resolution each program and each context demands, between experimental and indeterminate, which marked more than one generation of architects in Argentina and Latin America.

NOTES.-

1- Interview with Clorindo Testa for La Nación newspaper, 2011.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-

Bozzano, Nicolás et al. (2019) 12 artículos críticos sobre Clorindo Testa. Reflexión global a partir de enfoques particulares. Master of Advanced Architectural Design. FADU, UBA.

Fernandez, Roberto (1996) La ilusión proyectual: una historia de la arquitectura argentina. 1955-1995. Mar del Plata. Argentina: FADU, UNMDP.

Liernur, Jorge Francisco (2001) Arquitectura en la Argentina del siglo XX: la construcción de la modernidad. Buenos Aires. Argentina: Fondo Nacional de las Artes.

Montaner, Josep Maria (1999) Después del movimiento moderno: arquitectura de la segunda mitad del siglo XX. 4th. Edition. Barcelona. Spain: Gustavo Gili.

Montaner, Josep Maria (2002) Las formas del siglo XX. Barcelona. Spain: Gustavo Gili.

Shapira, Valeria (2011) Un tal Clorindo. Charla íntima con una leyenda viva de la cultura argentina. La Nación. Recovered from https://www.lanacion.com.ar/lifestyle/un-tal-clorindo-nid1365872/