IV. Indeterminate architecture.

“You're missing the main point. We don't arrange things in an order (that’s the function of the utilities). Quite simply, we are facilitating the processes so that anything may happen.”1

The concept of indeterminacy can be associated with a myriad of areas and approaches: physical, material, social and political; it can be both theoretical and practical, cognitive and experiential, among others. However, Cage’s indeterminate period mainly alludes to two issues already suggested in the other sections: the destruction of language and the open-sourced artwork. These two aspects are, of course, linked to that intention to depersonalize the work of art and to eliminate the authors' recurring self-referentiality, but, above all, to completely deconstruct the linearity of the narrative between all parts of the communication of a work.

What do we mean by this? That when the message reaches its last receiver (the public/user), little can be recognized of the initial message created by the author. This is precisely what chance and indeterminacy allow. The author creates an open, indeterminate work, which the interpreter makes their own, but not from their own subjectivity, but from other processes of chance or indeterminacy, to finally reach the ear (or any other sense) of the receiver. We could say then, that, in the thought of John Cage, his indeterminate works are not per se, but they pass through filters that are loading it with indeterminacy, while they go more and more, depersonalizing it.

Now, how can we identify a transposition or a reflection of this concept in architecture, eliminating the presence of the architect, being this a discipline so "necessarily" determined? How is that message dismembered and recomposed on its way from the architect to the user? How do we unlearn all the experience of architectural theory and practice to give rise to true indeterminate processes?

Compositional indeterminacy

Architecture, as a discipline, has inherently included a certain degree of indeterminacy. While a program determines the functions and spaces that a building must possess, the use that will be made of them, their durability over time and their impact on users are certainly undetermined. We can say then that architecture has a character rather predictive than conclusive, and it is from this that enter the game the figures of randomness, chance, probability, and even, why not, fortuity.

Many times, particularly towards the end of the last century, architecture (rather architects) has positioned itself in front of these subjects in an almost picaresque way, child of the own becoming of the discipline at that time, where that desire to eliminate the representation, ended in "simple" depictions that simulated random or accidental processes. However, these processes of legitimization of the work of architecture and of search for a value of authenticity2 by means of operations of imposition of random events of strictly determined form, are not those that here summon us.

Similarly, many architects and authors related to the discipline have referred over the last century, directly or not, to the concept of indeterminacy in more or less general terms, associated with the ideas of ambiguity and uncertainty: Richard Sennett did it in The Craftsman to define his concepts of strategy and resistance, alluding to the unknown, the unforeseen; Venturi in his well-known work Complexity and contradiction in architecture, referring more to ambiguity in terms of meaning; Rem Koolhaas has done so with architectural programs, both through his works and his way of representing them; Tschumi has also had contact with this notion to some extent, with his concepts of event and movement in architecture; De La Sota with his intention to "forget" his architectural formation to then project from the memory of other experiences and sensations apprehended; among others.

Although all these approximations are among the most varied (but not the gender of its authors), and may all be equally valid, not being intentionally linked to the Cageian indeterminacy, they do not correspond integrally with this concept. However, they all have one thing in common: the incorporation of the temporality variable.

When Solà-Morales introduces the concept of liquid architecture3 (taking up that comparison that opened the first paragraph of this essay) he ends up demolishing, precisely, these ideas of stability and permanence, typical of Western canonical architecture, introducing fluidity and time as structuring principles of discipline. It is from this that we find, although not directly referenced (he does refer to Fluxus, a movement of great relevance in the work of Cage), an important point of contact with the indeterminate thought of John Cage (especially with his first moments). Like Cage, Solà-Morales places his emphasis on the durée, on the duration proper to the development of the subject’s experience, and it is there that lies one of the keys to give place to multiplicity, change, event and indeterminacy.

Now, the temporality variable in architecture is, today, an intrinsic part of the discipline, and its relationship with indeterminacy is undeniable. However, considering only this aspect, it would still be possible to recognize the author’s hand in the work, an aspect to which Cage, as already mentioned, assigns great importance.

But we are forgetting another part, no less important, which concerns both the field of music, as well as that of architecture, painting or literature: violence. This concept can be approached from different positions regarding the subject of this essay, but the one that is particularly relevant to us is the one linked to the ideas of colonization and destruction worked by Ignasi de Solà-Morales.

"Architecture is aggressive against territory, against the material, which violates, manipulates, force, twists; it is violent against the existing forms, against the existing types and modes. All founding architecture is based on violence and has within it not so much a construction but also inseparably a destruction."4

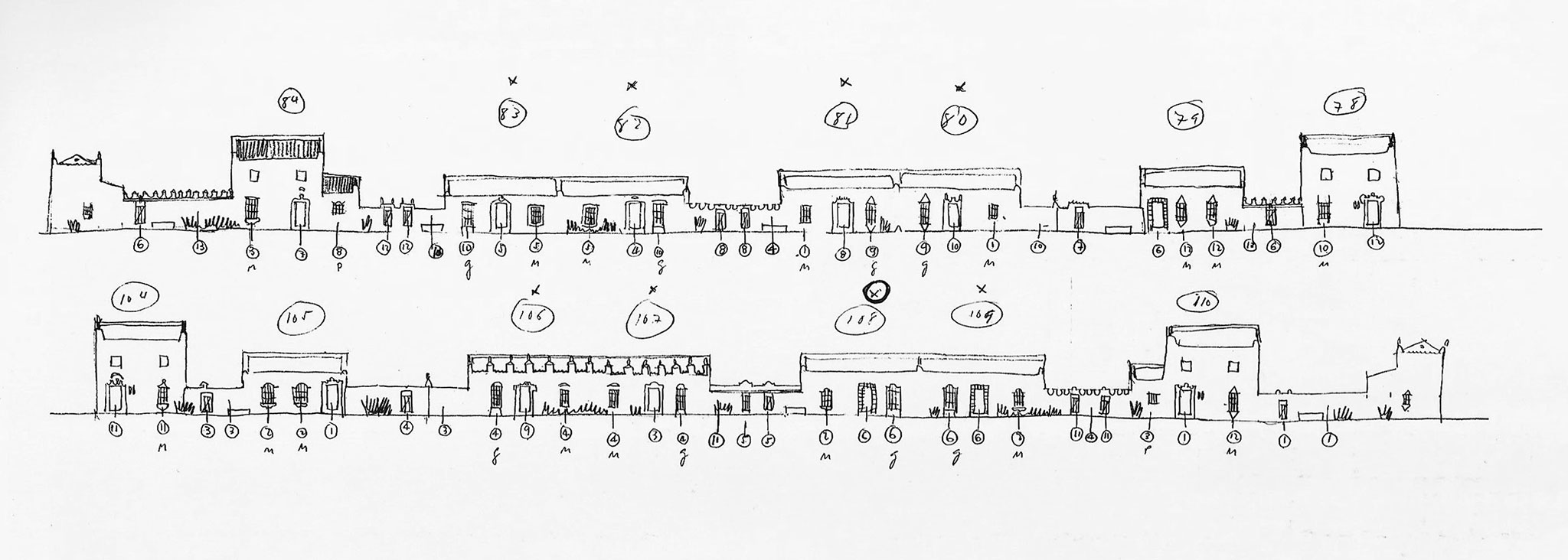

Considering this eloquent phrase, and recognizing then, that architecture is intrinsically violent (for better or worse), we must also clarify that, regarding the destruction of the language to which we are referring, is another violence, not the colonization of a territory, nor the one that forces the material, but the one that, precisely, is capable of destroying its own discourse, deconstructs and re-signifies its language and components in pursuit of new meanings that, perhaps, even escape its own designs. The case of the settlement town of Esquivel (Seville, 1952-63) of Alejandro de la Sota, may perhaps help us to recognize some processes with which to respond to this idea of eliminating the presence of the architect (significantly, at least).

As recovered by Miguel Guerra5, a Spanish architect with a professional degree in Music, De La Sota, faced with the commission of a village of "popular architecture", was pushed to seal his academic architectural formation (mostly in stylistic terms), to fully capture only through his senses the constructed landscapes of the place in which he had to intervene (Andalusia) to, time later, recover them from his memory and recompose them in his proposal. In this process, as John Cage does, the architect tries to annul his presence, or at least reduce it, stripping himself of his previous conceptions of architecture (is this even possible?), and thereby reduce the subjectivities inherent in any architectural design process.

Finally, regarding this notion of project or programmatic indeterminacy, it is pertinent to refer to the work of Rem Koolhaas and OMA, which, as already mentioned, has been linked to it from different aspects.

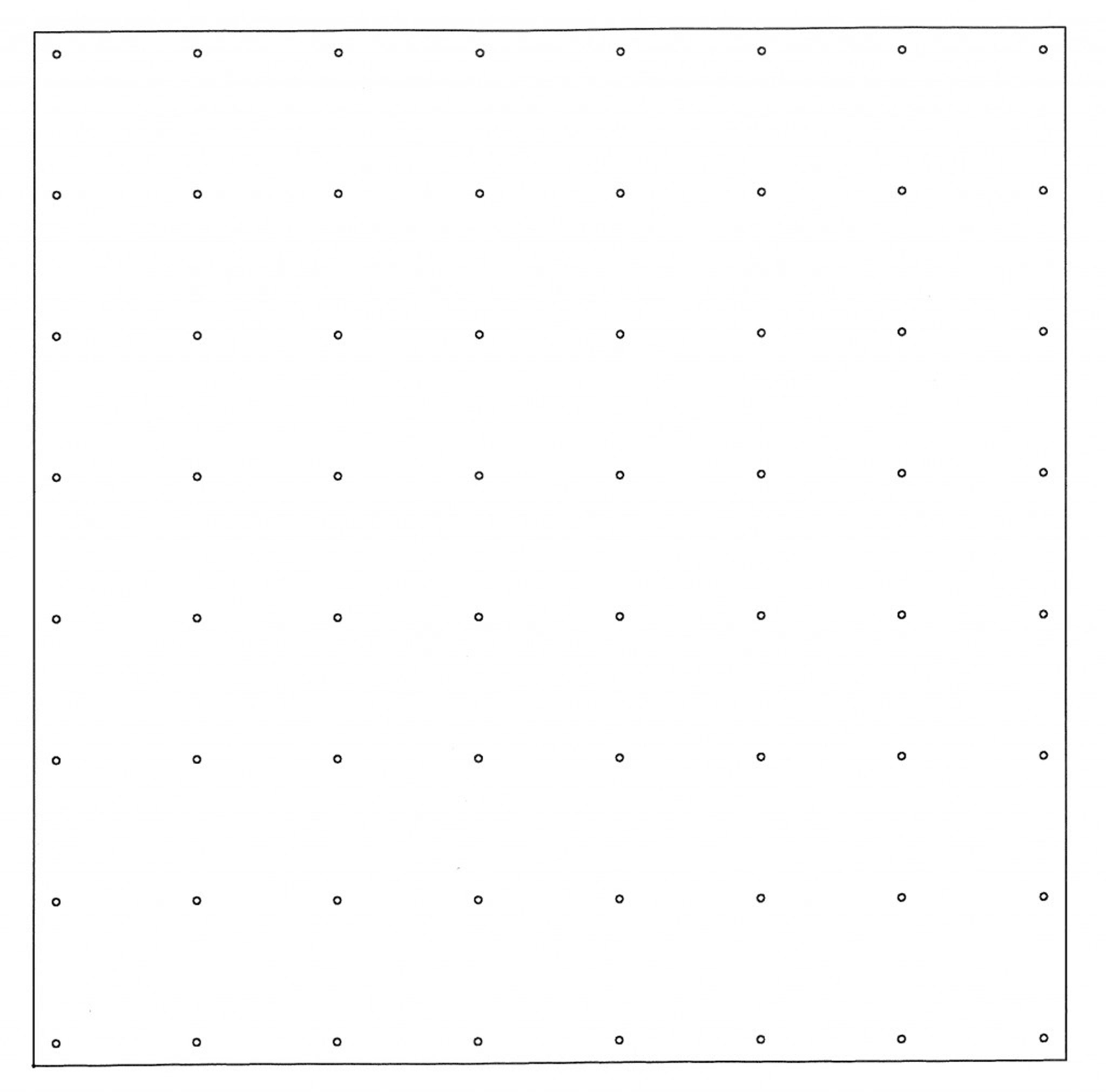

When one thinks about indeterminacy in architecture, it tends to associate it quickly to the ideas of flexibility, versatility or adaptability, and in the contemporary culture, this is linked, for good or bad, to the very diffused multifunctional spaces. This idea that the same space can accommodate different activities in its interior as they are required is valid, in fact, it has been extensively worked throughout the 20th century, with proposals such as the Maison Dom-Ino de Le Corbusier (1914-15) or the municipality of The Hague of OMA (1986). However, works like the latter certainly move away from the simplicity of the exhausted multipurpose spaces, traversed by much more complex backgrounds. To begin with, when Koolhaas describes his project for the city council competition, he carries all the baggage of his previous experiences, but especially with those concepts that he would later publish in Typical Plan and Generic City6, these ideas of instability and indeterminacy as the true nucleus of metropolitan life, where buildings, even with the burden of their planning for specific conditions, can adjust to unpredictable future demands, but now from a non-leading position, but rather from a background, almost infrastructural, where their neutrality and their not specificity give place to new territories for the fluid development of new urban processes, spaces conceived to enable almost everything, determining almost nothing7.

Rem Koolhaas uses the concept of indeterminate specificity to define the town hall of The Hague, rightly referring to its conception from a scheme of his Typical Plan, repeated throughout the twenty-four floors of the building, leaving as a result, perhaps, a scheme of architectural lobotomy very indebted to what he studied several years before about Manhattan8, and that defines from a sentence that also reminds us a lot of how John Cage defined his position in front of the indeterminacy: "Its only function is to let its occupants exist."9

Interpretative indeterminacy

"Another important consequence of thinking of the project as a musical composition, or drawing as a score, is that the architect appears as the one who develops his project while waiting for interpretation by the builder."10

As already mentioned, an important part in this process of deconstruction of language in pursuit of indeterminate creation processes is associated with the interpreter/constructor. He is in charge of transmitting a work to the listener/user and, as the composer does, he must in the process, shutter his subjectivities.

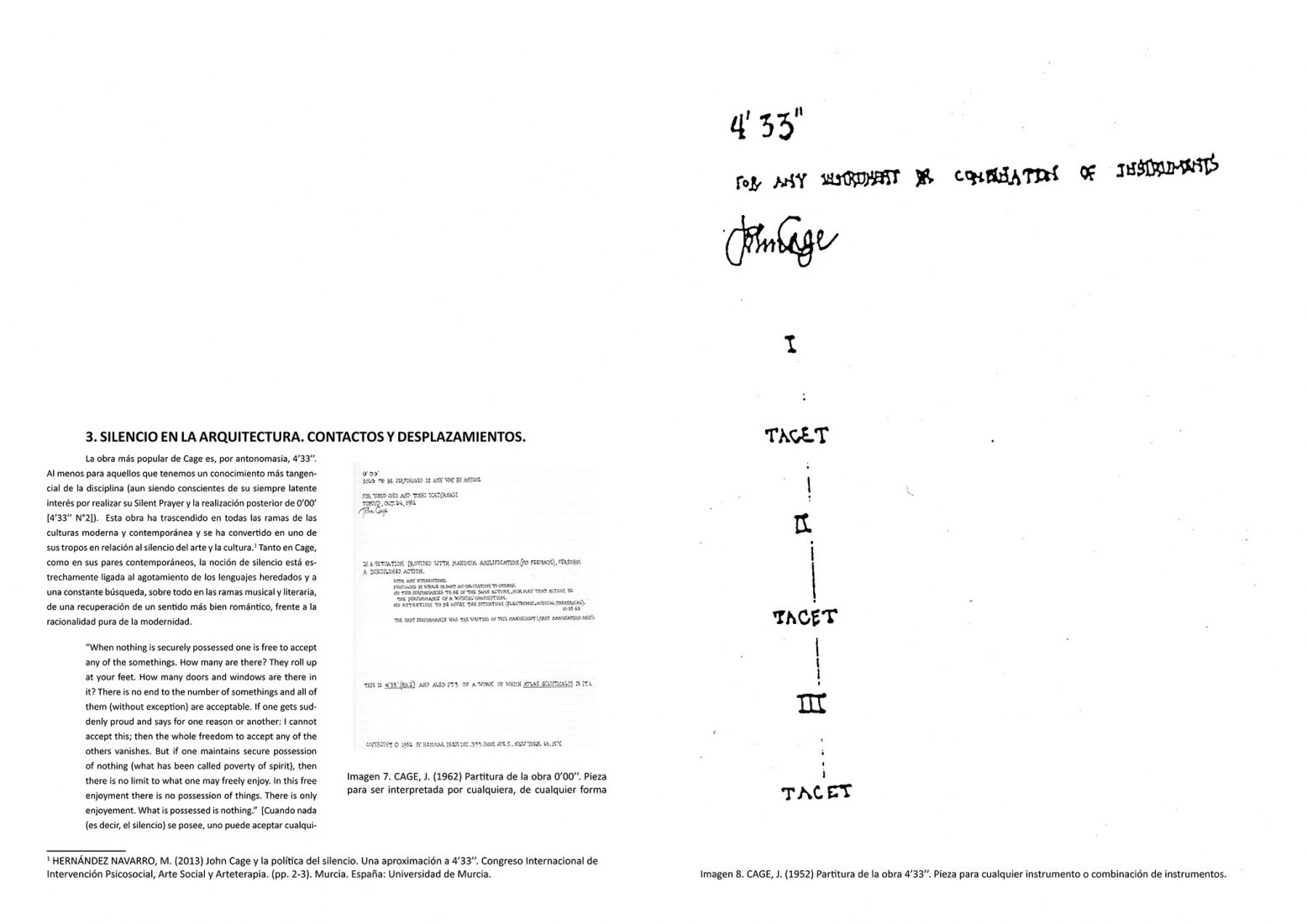

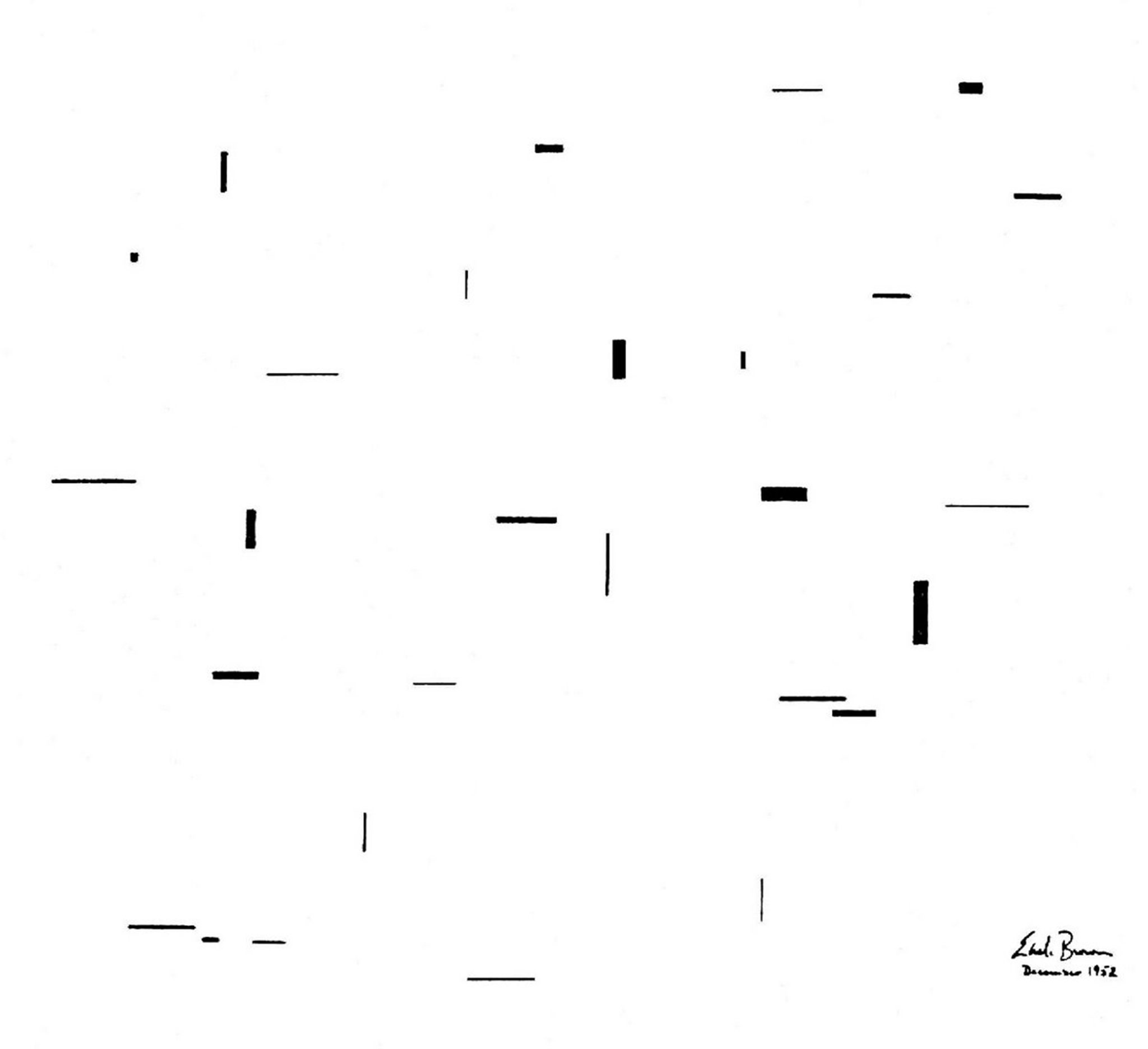

John Cage’s work, which had a much more determined beginning in this sense (remember that works like 4'33'' or Music of Changes were written to be performed by David Tudor), had its paroxysm in terms of indeterminacy with the discovery, by the composer, of the graphic notation (presented to Cage by his pupil Morton Feldman in 1951). Cage says, in this regard:

"This was characteristic of an old period, before the indeterminacy in the performance, you know, all I did then was give up the intention. Although my choices were controlled by random operation, I was still making an object."11

Music of Changes, one of the most famous works of the indeterminate period of Cage is, as its author recognizes it, extremely determined in interpretive terms. Although there would never be two equal interpretations, these would be easily recognizable as similar or parts of the same work, and this was because its structure, as well as the method, form and materials were all, to a lesser or greater extent, determined a priori by the composer.

"The function of the performer in the case of the Music of Changes is that of a contractor who, following an architect’s blueprint, constructs a building (...) But that its notation is in all respects determinate does not permit the performer any such identification: his work is specifically laid out before him. He is therefore not able to perform from his own center but must identify himself insofar as possible with the center of the work as written. The Music of Changes is an object more inhuman than human (...)"12

John Cage found in the experimental musical notation, a tool that matched perfectly the new projects in which he was dabbling and, in short, a quite logical strategy: new music, requires new ways. But of course, more than new methods, we could say that they are new applications, or even new perspectives compared to existing methods.

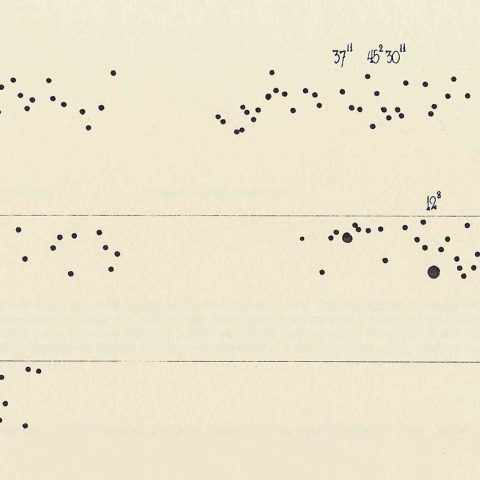

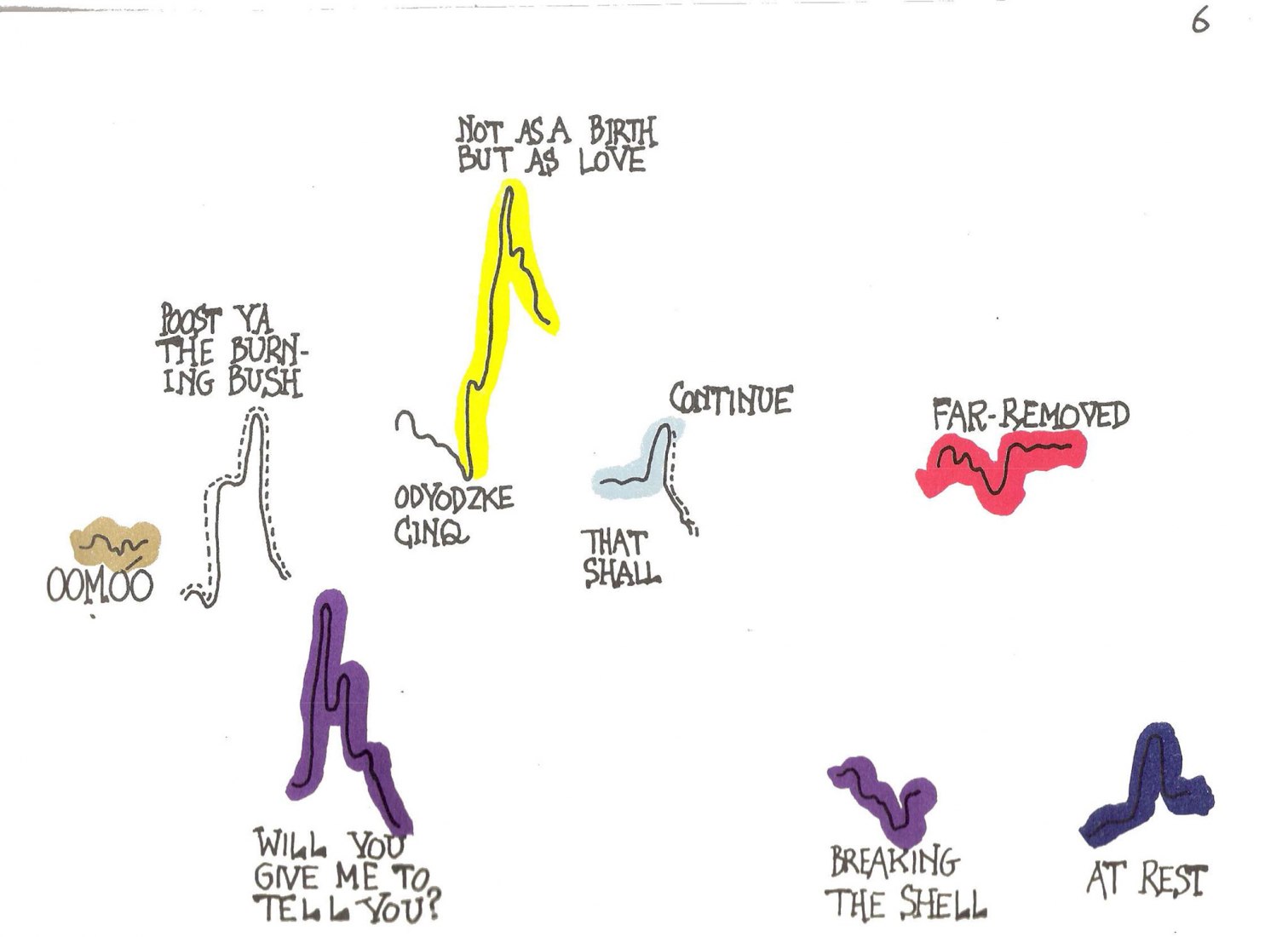

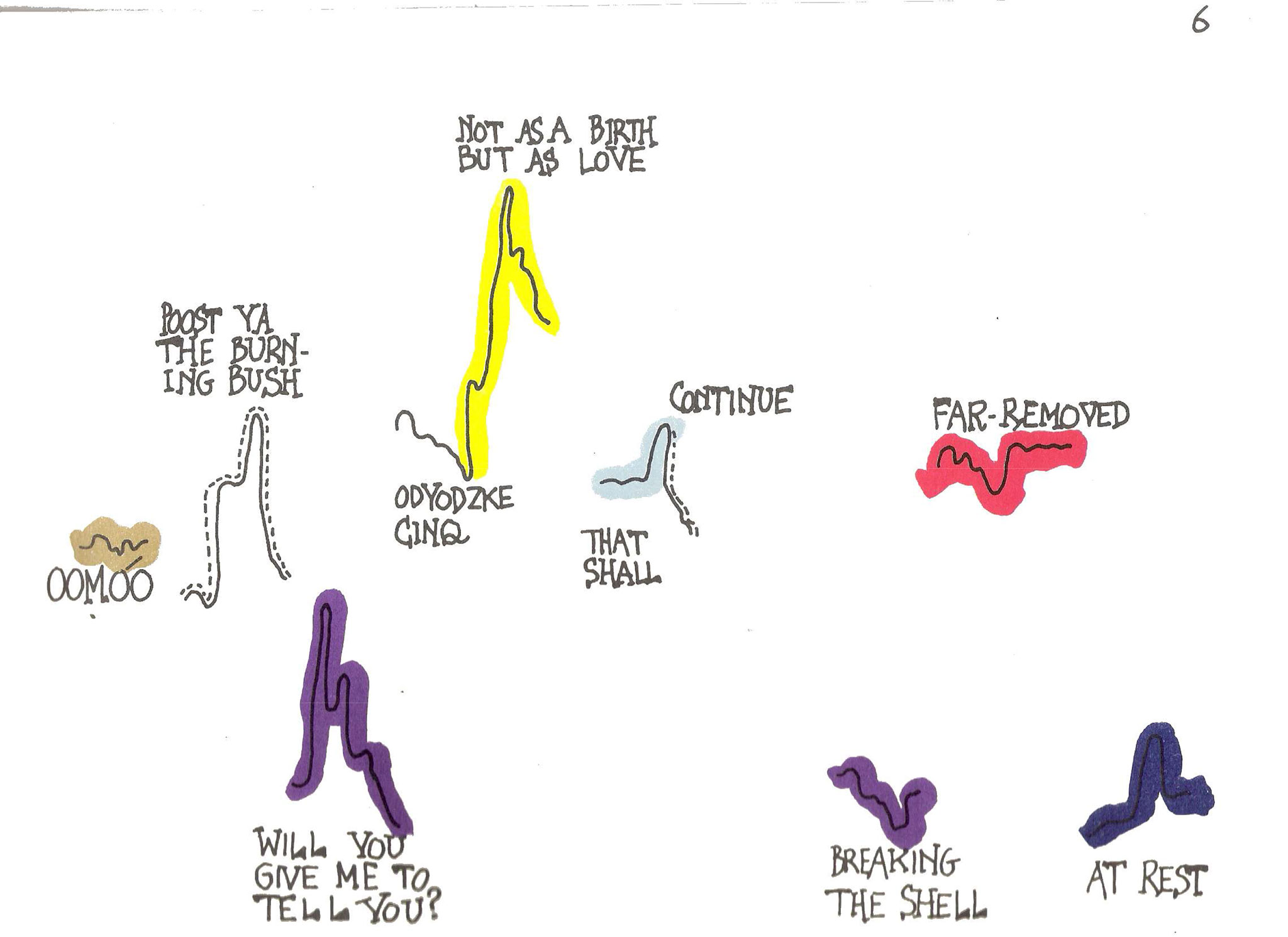

In the case of Aria13, for example, Cage reaches a high degree of indeterminacy, both compositional and interpretative. Although in principle it was composed to be interpreted by Cathy Berberian, the author limits himself only to asking questions (and suggestions) that must be answered by the interpreter, either from their own subjectivity, or from other methods of chance. Cage is limited here to a single introductory page with the "rules of the game", to then leave us with twenty pages loaded with multicoloured, irregular strokes and just a brief polyglot text.

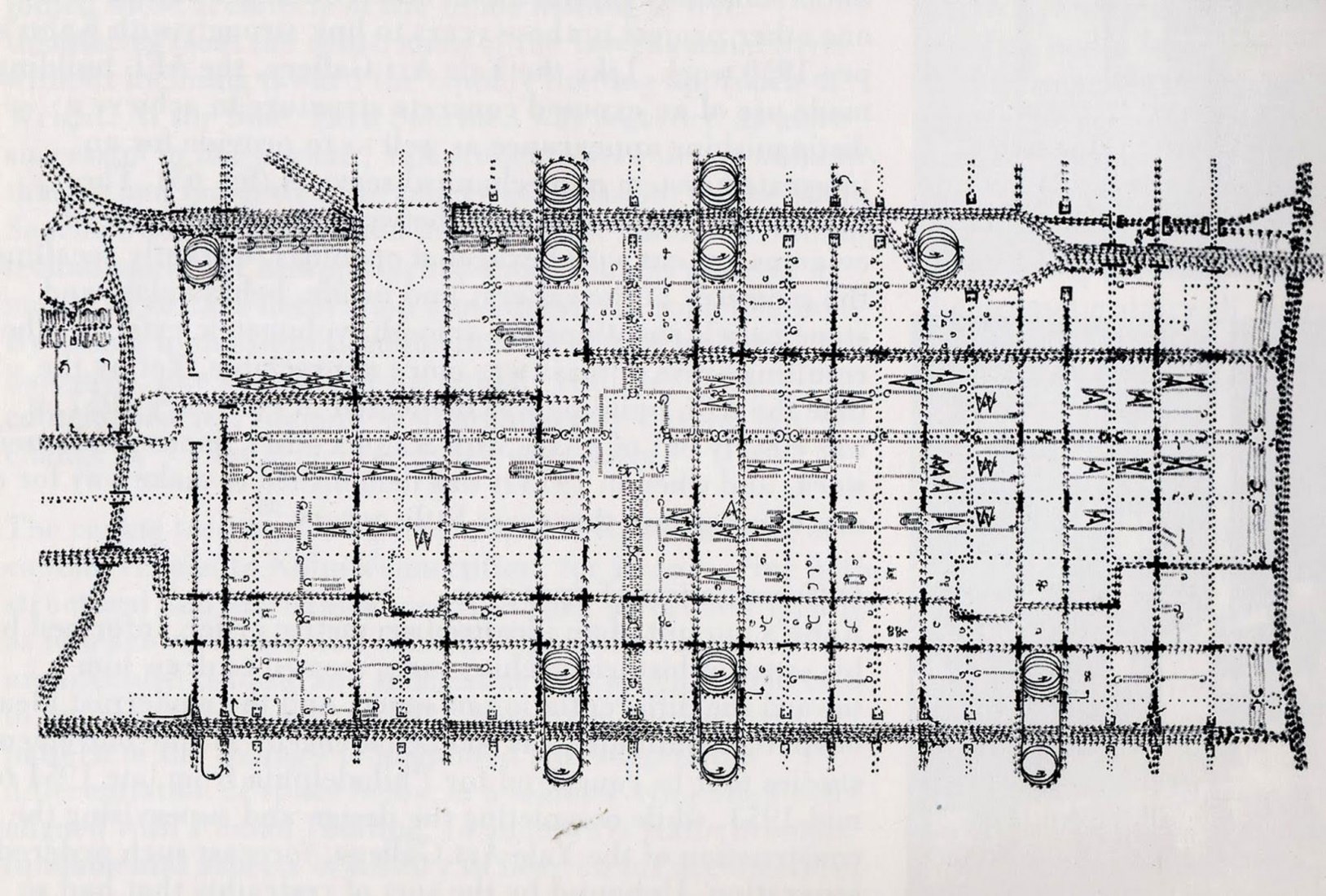

This criterion, which consists in revising how the message is transmitted (score-plane or score-drawing) has been quite explored especially in the last half of the 20th century. However, in most cases concerning architecture, the interpretation of these works has been left directly to the user/reader, since they have been mostly conceptual pieces or have remained in projects. Such is the case of many proposals of the Archigram, for example, or even of less utopian proposals such as the Plan for the center of Philadelphia, by Louis Kahn (1956), where the architect eliminated the notion of urban space defined from the built mass, to represent it from the flows that passed through it and that, in short, defined it.

However, how is it possible to eliminate that desire of intentions that lays behind any graphical representation in architecture, that exhaustive and detailed determination that accompanies every constructive detail up to scales 1:1?

Of course it is impossible to find a single answer to this question, however, a relevant case to illustrate the relevance of the role of the interpreter in the decoding and reformulation of that message, starting from the given indeterminacy (intentionally or not) by the architect, is that of the house Curutchet, work of Le Corbusier, interpreted and directed (until 1954) by the Argentine architect Amancio Williams.

The particularity of this case, carefully studied by Daniel Merro Johnston in El autor y el intérprete14, is that the interpretation is carried out, not by the builder or contractor, but by another architect in charge of the direction of the work. Here, Williams' hermeneutical work resided in an extensive process of design and redesign, drawing and redrawing, composing and recomposing of each part of the work. It is precisely in this complicity between both professionals, and in the "openness" of the Master to the interpretations made by Williams, where we can find that notion that reminds us of the original intentions of Cage when performing his indeterminate works, to dispel the intentions of the composer in the process, to such an extent that, even today, it is still difficult to answer the question of who was, in fact, the author of the work for Dr. Curutchet in La Plata.

We must then recognize that one of the key roles in this process must be attributed to the performer of the work, not to the detriment of the value of the composer/architect, without which there would not be a work on which to act, but as part of a dialogical relationship, to which we could even place at a stage of transfiguration (between Ricoeurian configuration and refiguration), where before the reader/user makes their final interpretation of the work, the interpreter/builder does their own thing from their creative mimesis, shaping their own representation of what the author did at first instance.

V. There are no final thoughts (or is there time for conclusions?)

NOTES.-

1.- CAGE, J. (1981) For the Birds: John Cage in Conversation with Daniel Charles. (p. 25) Canada: Marion Boyars Inc.

2.- DIEZ, F. (2008) Crisis de autenticidad. Cambios en los modos de producción de la arquitectura argentina. Buenos Aires. Argentina: Summa+

3.- SOLÀ-MORALES, I. (2002) Arquitectura Líquida. Territorios. (pp. 122-135) Barcelona. Spain: Gustavo Gili.

4.- SOLÀ-MORALES, I. (1993) Lecture given as part of the Anyway congress at the Centre for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona. Barcelona. Spain. Cited in BARBA, J. J. (2019) Anyway. La ciudad de las ciudades. Madrid. Spain: Fundación Arquia.

5.- GUERRA, M. (2017) La no música y la no arquitectura. John Cage y Alejandro de la Sota en paralelo. Cuadernos de proyectos arquitectónicos, vol. no. 7, (pp. 4-5). Madrid. Spain: DPA-Prints, ETSAM.

6.- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). S, M, L, XL. New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

7.- BÖCK, I. (2015) Six canonical projects by Rem Koolhaas. Essays on the history of ideas. Architektur + analyse, vol. 5. (p. 246) Graz. Austria: Jovis Verlag GmbH.

8.- KOOLHAAS, R. (1994) Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. (pp. 100-101) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

9.- Op. Cit. 6 (p. 337)

10.- BALDEWEG, N. (2016) Alejandro de la Sota: Construir, habitar. In Minerva: Revista del Círculo de Bellas Artes. No. 3. (p. 7). Madrid. Spain: Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid.

11.- KOSTELANETZ, R (1970) Entrevista a John Cage. (p. 36) Barcelona. Spain: Anagrama.

12.- CAGE, J. (2011) Composition as process. In Silence. Lectures and writings, 50th Anniversary Edition (2nd ed.) (p. 36) Connecticut. United States: Wesleyan University Press.

13.- CAGE, J. (1958) Aria. Piece for voice only.

14.- MERRO JOHNSTON, D. (2011) El autor y el intérprete. Le Corbusier y Amancio Williams en la casa Curutchet. Buenos Aires. Argentina: 1:100 Ediciones.

2.- DIEZ, F. (2008) Crisis de autenticidad. Cambios en los modos de producción de la arquitectura argentina. Buenos Aires. Argentina: Summa+

3.- SOLÀ-MORALES, I. (2002) Arquitectura Líquida. Territorios. (pp. 122-135) Barcelona. Spain: Gustavo Gili.

4.- SOLÀ-MORALES, I. (1993) Lecture given as part of the Anyway congress at the Centre for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona. Barcelona. Spain. Cited in BARBA, J. J. (2019) Anyway. La ciudad de las ciudades. Madrid. Spain: Fundación Arquia.

5.- GUERRA, M. (2017) La no música y la no arquitectura. John Cage y Alejandro de la Sota en paralelo. Cuadernos de proyectos arquitectónicos, vol. no. 7, (pp. 4-5). Madrid. Spain: DPA-Prints, ETSAM.

6.- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). S, M, L, XL. New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

7.- BÖCK, I. (2015) Six canonical projects by Rem Koolhaas. Essays on the history of ideas. Architektur + analyse, vol. 5. (p. 246) Graz. Austria: Jovis Verlag GmbH.

8.- KOOLHAAS, R. (1994) Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. (pp. 100-101) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

9.- Op. Cit. 6 (p. 337)

10.- BALDEWEG, N. (2016) Alejandro de la Sota: Construir, habitar. In Minerva: Revista del Círculo de Bellas Artes. No. 3. (p. 7). Madrid. Spain: Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid.

11.- KOSTELANETZ, R (1970) Entrevista a John Cage. (p. 36) Barcelona. Spain: Anagrama.

12.- CAGE, J. (2011) Composition as process. In Silence. Lectures and writings, 50th Anniversary Edition (2nd ed.) (p. 36) Connecticut. United States: Wesleyan University Press.

13.- CAGE, J. (1958) Aria. Piece for voice only.

14.- MERRO JOHNSTON, D. (2011) El autor y el intérprete. Le Corbusier y Amancio Williams en la casa Curutchet. Buenos Aires. Argentina: 1:100 Ediciones.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-

- BALDEWEG, N. (2016) “Alejandro de la Sota: Construir, habitar. En Minerva: Revista del Círculo de Bellas Artes. No. 3. (pp. 117-124). Madrid. Spain: Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid

- BARBA, J. J. (2019) Anyway. La ciudad de las ciudades. Madrid. Spain: Fundación Arquia.

- BÖCK, I. (2015) Six canonical projects by Rem Koolhaas. Essays on the history of ideas. Architektur + analyse, Vol. 5. Graz. Austria: Jovis Verlag GmbH.

- CAGE, J. (1981) For the Birds: John Cage in Conversation with Daniel Charles. Canada: Marion Boyars Inc.

- CAGE, J. (2011) Silence. Lectures and writings, 50th Anniversary Edition (2nd ed.) Connecticut. United States: Wesleyan University Press.

- CONDE, Y. (2000) Arquitectura de la indeterminación. Madrid. Spain: Actar.

- DIEZ, F. (2008) Crisis de autenticidad. Cambios en los modos de producción de la arquitectura argentina. Buenos Aires. Argentina: Summa+

- GARCÍA BALLESTEROS, E. (2013) Desde John Cage: 4'33" como fin de toda obra. Vigo. Spain: Universidad de Vigo.

- GUERRA, M. (2017) La no música y la no arquitectura. John Cage y Alejandro de la Sota en paralelo. Cuadernos de proyectos arquitectónicos, vol. no. 7, (pp. 146-161). Madrid. Spain: DPA-Prints, ETSAM.

- HERNÁNDEZ NAVARRO, M. (2013) John Cage y la política del silencio. Una aproximación a 4’33’’. Congreso Internacional de Intervención Psicosocial, Arte Social y Arteterapia. (pp. 1-14). Murcia. Spain: Universidad de Murcia.

- JOSEPH, B. (1997) John Cage and the Architecture of Silence. October magazine, vol. 81, summer, (pp. 80-104). Nueva York. United States: MIT.

- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). Indeterminate Specificity. En S, M, L, XL. (pp. 544-569) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). The generic city. En S, M, L, XL. (pp. 1238-1269) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). Typical Plan. En S, M, L, XL. (pp. 334-353) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOOLHAAS, R. (1994) Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOSTELANETZ, R (1970) Entrevista a John Cage. Barcelona. España: Anagrama.

- MERRO JOHNSTON, D. (2011) El autor y el intérprete. Le Corbusier y Amancio Williams en la casa Curutchet. Buenos Aires. Argentina: 1:100 Ediciones.

- MISHRA, J., SHRIVASTAVA, V. & SINGH, A. (2017) Silence of Architecture. International Journal on Emerging Technologies. Vol. 8, no. 1 (pp. 67-74). India: Research Trend.

- PETRESCU, D., TYSZCZUK, R. (2007) Architecture & Indeterminacy. Field journal, vol. 1, no. 1. Sheffield. United Kingdom: Field.

- SICCARDI, R. (2018) Silence in architecture and music. Viena. Austria: TUWIEN

- SOLÀ-MORALES, I. (2002) Arquitectura Líquida. En Territorios. (pp. 122-135) Barcelona. Spain: Gustavo Gili.

- BARBA, J. J. (2019) Anyway. La ciudad de las ciudades. Madrid. Spain: Fundación Arquia.

- BÖCK, I. (2015) Six canonical projects by Rem Koolhaas. Essays on the history of ideas. Architektur + analyse, Vol. 5. Graz. Austria: Jovis Verlag GmbH.

- CAGE, J. (1981) For the Birds: John Cage in Conversation with Daniel Charles. Canada: Marion Boyars Inc.

- CAGE, J. (2011) Silence. Lectures and writings, 50th Anniversary Edition (2nd ed.) Connecticut. United States: Wesleyan University Press.

- CONDE, Y. (2000) Arquitectura de la indeterminación. Madrid. Spain: Actar.

- DIEZ, F. (2008) Crisis de autenticidad. Cambios en los modos de producción de la arquitectura argentina. Buenos Aires. Argentina: Summa+

- GARCÍA BALLESTEROS, E. (2013) Desde John Cage: 4'33" como fin de toda obra. Vigo. Spain: Universidad de Vigo.

- GUERRA, M. (2017) La no música y la no arquitectura. John Cage y Alejandro de la Sota en paralelo. Cuadernos de proyectos arquitectónicos, vol. no. 7, (pp. 146-161). Madrid. Spain: DPA-Prints, ETSAM.

- HERNÁNDEZ NAVARRO, M. (2013) John Cage y la política del silencio. Una aproximación a 4’33’’. Congreso Internacional de Intervención Psicosocial, Arte Social y Arteterapia. (pp. 1-14). Murcia. Spain: Universidad de Murcia.

- JOSEPH, B. (1997) John Cage and the Architecture of Silence. October magazine, vol. 81, summer, (pp. 80-104). Nueva York. United States: MIT.

- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). Indeterminate Specificity. En S, M, L, XL. (pp. 544-569) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). The generic city. En S, M, L, XL. (pp. 1238-1269) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOOLHAAS, R. & MAU, B. (1995). Typical Plan. En S, M, L, XL. (pp. 334-353) New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOOLHAAS, R. (1994) Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. New York. United States: The Monacelli Press.

- KOSTELANETZ, R (1970) Entrevista a John Cage. Barcelona. España: Anagrama.

- MERRO JOHNSTON, D. (2011) El autor y el intérprete. Le Corbusier y Amancio Williams en la casa Curutchet. Buenos Aires. Argentina: 1:100 Ediciones.

- MISHRA, J., SHRIVASTAVA, V. & SINGH, A. (2017) Silence of Architecture. International Journal on Emerging Technologies. Vol. 8, no. 1 (pp. 67-74). India: Research Trend.

- PETRESCU, D., TYSZCZUK, R. (2007) Architecture & Indeterminacy. Field journal, vol. 1, no. 1. Sheffield. United Kingdom: Field.

- SICCARDI, R. (2018) Silence in architecture and music. Viena. Austria: TUWIEN

- SOLÀ-MORALES, I. (2002) Arquitectura Líquida. En Territorios. (pp. 122-135) Barcelona. Spain: Gustavo Gili.