Let's start with the trauma. The Fontán Building does not manifest that trauma. The Fontán Building mobilizes collaborating sheets, beams, latex, pipes, and glass to celebrate the reopening of Mount Gaias, as ecosystemic; as fabric and flow of relationships, of porosities, of compactness and material solidarities, of life and activism. The Fontán celebrates what is yet to come.

Give me an Architecture, and I will change the world

The Fontán building is set on the ruins of the last half-finished abandoned building of the City of Culture complex. The works were suspended before the granite cladding, false ceilings, and floating floors arrived. What remains of the building designed by Eisenman is what he never thought would be seen.

City of Culture overview - AEROrec / Francisco Muradas, courtesy of Xunta de Galicia.

Andrés Perea, Elena Suárez, and Rafael Torrelo, together with a large and diverse team of professionals and artists, have re-founded the material practices as the space from which to build the encounter of the diverse, the changing, the collective. This is a manifesto of the impossibility of segregating politics, technology, and life; and of the impossibility of a disconnected architecture. Give me architecture and I will change the world. They don't know what they have done in the Xunta: Perea, Suárez, and Torrelo, they have given them a foothold, and they have changed the world.

Andrés Perea

It is above all the result of what a continuous work of invention, experimentation, collaboration, and commitment can achieve. I am referring to Andrés Perea, who together with Suárez and Torrelo at Fontán, and together with many, many others, over four decades now, has made possible the context and knowledge in which many of us are possible.

We tend to think that architecture responds to the needs of society. This does not apply in the case of Andres Perea, it is societies that are reconstructed through his work. Perea multiplies the spectrum of the possible. Perea invents the possible.

Against prophylaxis

We live in prophylactic environments. I write on a chair varnished with polyurethane molecules, on a technical floor of wood impregnated with phenol, on a rubber waterproofing membrane, and a concrete slab with fireproofing additives. On the ninth floor, all these layers are repeated nine times until reaching the ground. Twenty-seven layers of waterproofing separate me from the ground. I have never seen the ground on which I stand. We live encapsulated. That is what much of architecture does. Architecture has been understood as the encapsulation of human individuality. But that never really works. Life, human or non-human, depends on porosity, exchange, on mutual infiltration between different entities. We are sweat, oxygen from our blood, which is exchanged in the lungs and incorporated into other bodies. We are water, urine, virus, feces, and nutrients. Breathing, decomposing, menstruating, ejaculating, ventilating, spitting, and crying are what keep us alive. Our existence, as Astrida Neimanis explains, is a wet collectivity. Pipes, manholes, ventilation ducts, waterproofing membranes, floor slabs. Architecture is the interlocution of our humid collectivity.

From disgust to eroticism

The basis of ecology is the impossibility of the individual. The inevitable certainty that life depends on how some of us infiltrate others. We are ecology, sweaty ecology. We are composed of oxygen that was once part of the blood of others. And there is nothing that repulses a colonial body as much as being formed by the other. Architecture has been understood as the control of flows. Perhaps as control overflows; as the possibility of infiltrating, without being infiltrated. Undoubtedly, as the evacuation of the alien.

In the words of Andrés Perea, architecture arises from "fruition" and "eroticism". From the uncontrolled flows, from the enjoyment of compactness, and material solidarity among the diverse. In his text "Prologue to the past. Objectives for architectural design", Perea, Suarez, and Torrelo say:

"Understood as the science that studies the relationship of living beings among themselves and with the environment, this project is defined as radically ecological."

It is not ecological because it simply reduces its carbon footprint, it is ecological because it contributes to making very clear, to feel, to tune our senses to the collective and interdependent dimension of lives.

Monte Gaiás previous state to Cidade da Cultura project, via Andrés Jaque.

The ecosystem overflows the site

In the previous image, you can see Mount Gaias, as it was before the City of Culture project began. Probably for Peter Eisenman this was a site. The notion of the site in architecture seems to speak of an empty fragment of land, defined by its future, not by its past or present; that does not participate in ecosystemic structures, nor social relations. However, those who know Santiago de Compostela, know that Mount Gaias had great importance for those who depended on it. Many used it as pasture for their animals, and as a space for recreation. It was a mountain with an important presence of non-human life, and that regulated the climate of an entire area. It is very important to pay attention to how the kind of considerations that were overlooked in projecting this place as a mere plot of land - economic, political, environmental, and material - are the ones that ended up paralyzing the construction of Peter Eisenman's project. They have paralyzed it politically, financially, technologically, socially, and ecologically. The Fontan project comes to operate within/as-reaction-to-a-collapse. Something very important: ecology, as a reading of Mount Gaias, has prevailed over that of "solar."

Returning to the ground.- the earthly is relational. The earthly is not a blank canvas. All construction is a reconstruction. Architecture always operates on what exists.

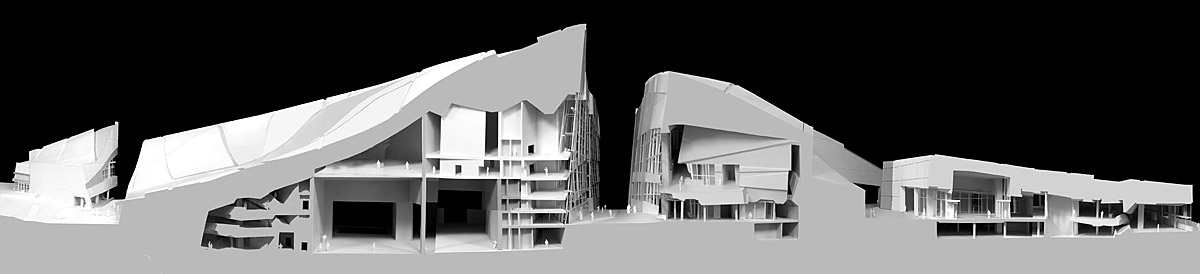

Exhibition of the model of the Cidade da Cultura - Courtesy of Xunta de Galicia.

The model of Peter Eisenman's competition proposal for the City of Culture evidences a sense of guilt. As Lacan teaches us, form often tries to express being what it does not want to be. Eisenman had little interest in Mount Gaias, but he nevertheless reproduced a kind of topography, a kind of landscape, a landscape that petrified a form generated employing simple digital modeling tools, which simulated but in reality ignored the geological, biological and social complexity of the mountain. A kind of fake Mount Gaias.

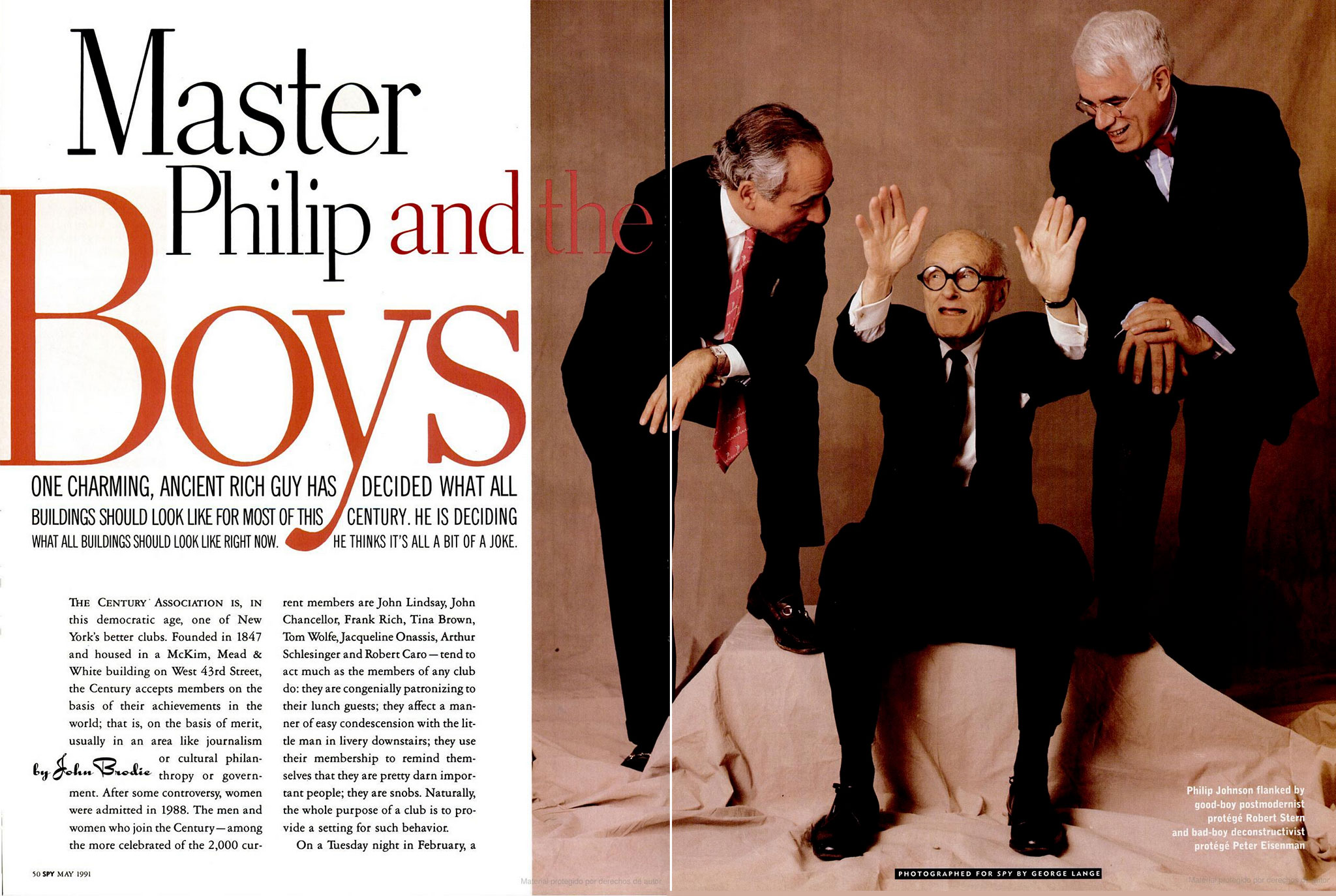

Philip Johnson flanked by Robert Stern and Peter Eisenman - Photographed for magazine SPY by George Lange (May 1991).

Genealogies

In this photograph, we can see Peter Eisenman next to Philip Johnson, instigator, and promoter in part of the cultural context in which the thinking of Eisenman's generation was forged. Philip Johnson was involved in a long list of unique projects that often became major political conflicts, because of the kind of relationship they established with the land on which they sat.

The Lincoln Center project by Philip Johnson, Abramovitz, Saarinen, and Wallace was a bid for the elimination of the relational structure on which the ensemble of buildings that would come to form the center, dedicated to the promotion of the performing arts, sat.

Lincoln Center Restart Stages / Courtesy of Lincoln Center, via ajay_suresh under CC 2.0.

During the groundbreaking of the work (a ceremony known in English as the breaking of the ground) U.S.A President D. Eisenhower, breaking the ground, said, "This is how art pays homage to the land."

President Eisenhower Breaking Ground at Lincoln Center - Photograph by Bob Serating (1959) Courtesy of Google Arts & Culture, via Andrés Jaque.

The ground the president was breaking looked like a smooth, accident-free ground that he was breaking to begin to introduce complexity into it, complexity it had never had before. But in reality, this ground that President Eisenhower broke was a manufactured ground, a flattened ground, a purpose-made ground, like Eisenman's pretend Mount Gaias.

Lincoln Center groundbreaking, May 14, 1959. Photograph courtesy of the Rockefeller Archive Center.

Eisenhower's constructed soil, concealed how to generate the Lincoln Center site the Puerto Rican population of the San Juan Hill neighborhood had been displaced and their homes demolished. That false ground that President Eisenhower tore up, concealed with its abstraction the crimes that preceded the neat architecture of Lincoln Center. There is no way to justify it. San Juan Hill was where Thelonious Monk gave his concerts and lived. The place where Herbie Nichols developed many of the techniques and innovations in jazz through his piano. We will never know what would have emerged from a Lincoln Center that would have helped to empower what already existed at San Juan Hill.

Interim Park, Bronx. Vacant lot for future Interim Park site, April 1980. Photograph by Paul Rice. Photograph courtesy of New York City Department of Records and Informations.

The next image shows the beginning of work on the City of Culture. This is the first time I went to this place, invited by Andrés Perea, who I don't know how he had convinced the project managers to let me intervene in the works. In these clearings, we can see how much of the richness of Mount Gaias had already disappeared. For me, this image of the clearing of Mount Gaias and San Juan Hill reduced to rubble, speaks of the same architectural paradigm, and the same anti-ecological notion of the site.

Construction of the service road for the Cidade da Cultura, Photograph by Constructora San José, via Andrés Jaque.

After the definitive halt of the construction works of the building of the Theater of the City of Culture of Galicia, where most of the structure of the eastern part of the Theater had been built, the Cidade da Cultura Foundation decided to reuse, condition, and complete the structure already built in order to give it an institutional use and transform it into an architectural complex.

Against poché

When we see the models of Peter Eisenman's buildings, the first thing that catches our attention is the fatness of the last layer of the section. That fatness for Eisenman is the space of the autonomy of architecture, where the physical structure is segregated from the symbolic structure of the building. We must remember that this split between structure and symbolism has been one of the theoretical arguments on which Eisenman's work has been based.

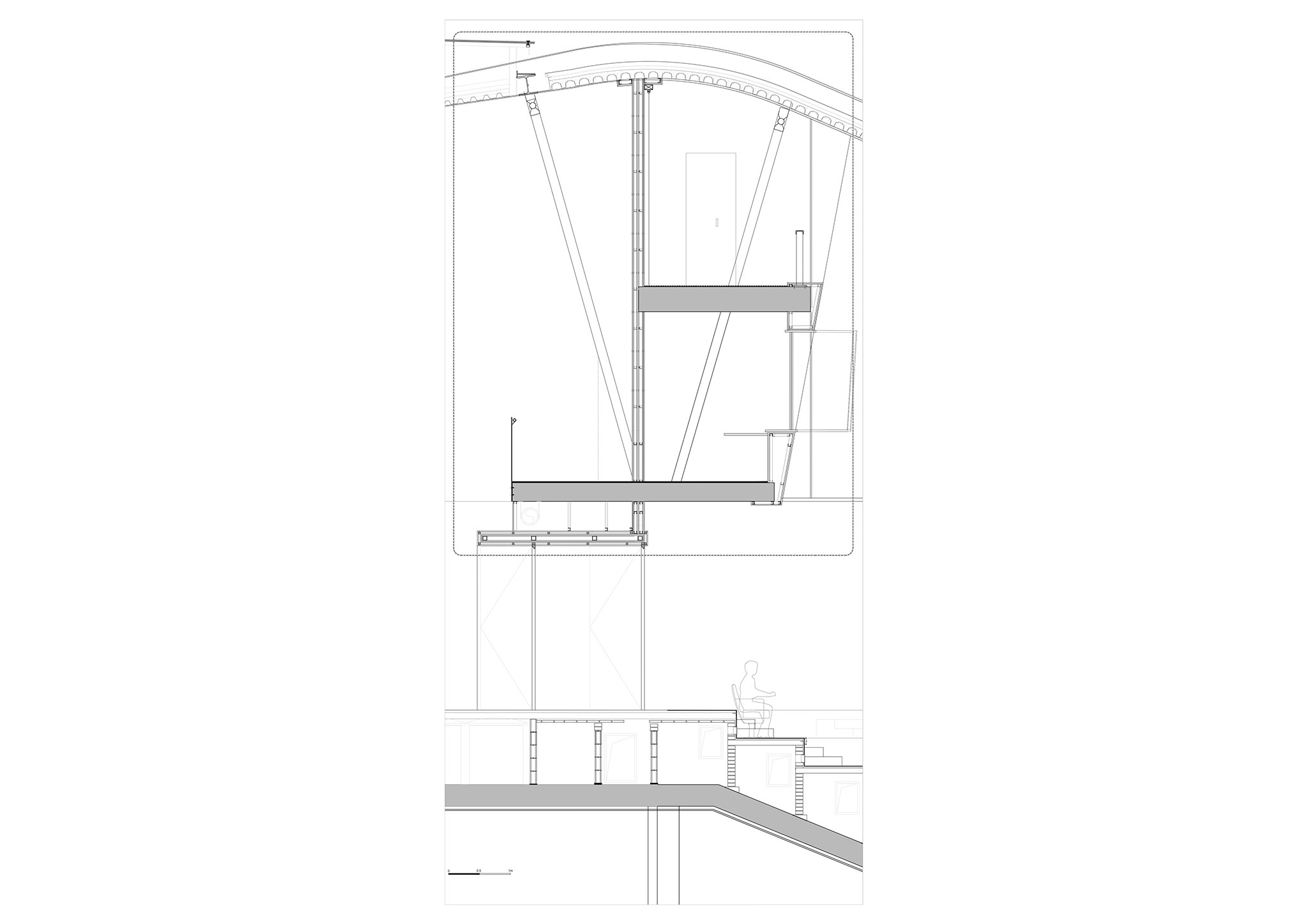

Eisenman Architects, Section Model, 2004.

Long live lightness

In contrast to the efforts of Eisenman's original project to generate large masses constituted by superimposing layers, dedicated to concealing the building's structure and installations, the Fontán Building is shown as a naked building that evidences the processes that constitute it. In these design decisions, the elimination of an entire poché, makes the building emerge as different from the surrounding buildings. If we pay attention to the plan of the roof section and the slabs of the Fontán building, it is easy to perceive that there is a great insistence on lightness, which is a way of dismantling the layers that separate, and that encapsulate, and a way of denying prophylaxis, a commitment to multiple presences.

If we superimpose the Fontan section on Eisenman's, we see that the lightness in the Fontan architecture is an act almost of disobedience. It is an active effort to undo, and to deny the possibility of segregating architecture from the world of the material, from the world of the social, from the world of the ecological; from the installations, from the structures, from the landscapes, from the flows, from the other presences.

Detail of the roof section of the Fontán Building. Fontán building by Andrés Perea, Elena Suárez, Rafael Torrelo.

Perea, Suarez, and Torrelo say "No technical floor will be used". Something they emphasize as if it were a biblical mandate (although they immediately qualify it by saying "except in the racord room" in a show of love for truth over solemnity), they are already talking about the elimination of layers, podiums, carpets, of everything that separates and encapsulates. The Fontán is an alliance with the porous, a celebration of infiltration.

Architecture is dissidence

When we see photographs of the Fontán, along with the rest of the buildings of the City of Culture, we see how this building has something of an unwanted guest. In these times of lying ecology, ecology, radical ecology, is dissidence, it is a form of dissidence to that impossible architectural order of the prophylactic, of the autonomous. Ecology, as Fontán teaches us, is socio-material dissidence.

Fontán building by Andrés Perea, Elena Suárez, Rafael Torrelo. Photograph by Ana Amado.

Fontán, or the love of technique

I would like to end with the sentence with which Fontán ends the book: "The era of light things will come; In the Fontán Building architecture follows the sign of the times and is losing weight, it is the constructed story of technical reality", and I would like to stop at the word "sign" where there is a kind of promise and commitment that the symbolic is not segregated from the real, is not segregated from the rational, is not segregated from the material, and is not segregated from the systemic in the last analysis. And I would also like to underline the word "technique". A mantra for Andrés Perea. For Andrés Perea, there is no better mediator than technique. There is no better space for politics than technique. There is no greater space for joy than technique. For him, the technique is not a space of exclusion, but of negotiation and eroticism. The place where San Juan Hill could have gained continuity, and where Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols could have connected with so many others that Lincoln Center summoned. This is now possible in the Fontan Building, and in many of the works that will follow the paths that this building makes possible.