The Pompidou Center, one of the main cultural attractions of the French capital, partly represents as a swan song of an optimistic period and confident in the ability of technology to solve problems, emerged after the end of World War II, the exemplification of the theories of mobility, flexibility and indeterminacy that arose at the end of the 1950s with the idyllic world of megastructures and their popularization among architects with their drawings and "pop" proposals in the 1960s.

The Centre Pompidou in Paris, photographed in 2018. Photograph by G. Meguerditchian/ © Centre Pompidou, 2020

The project shows from its conception some of the main ideas of its authors, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, a close relationship with the city where half of the total available area of the site was reserved as a public square, which conditioned the height of the Center for to be able to house its 90,000 m².

The project takes as its own characteristics those raised by different authors for the megastructures at the end of the 1950s, movement and anti-monumentalism. They assume as characteristic of their future architecture to expose the structure, bet on technology and propose a great programmatic flexibility, aspects that will mark the architecture of Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers.

The decision to place the structure and services outside was driven by the need for internal flexibility, as a result, large surfaces of space are generated in open floors: the astonishing scale of these internal spaces was left free from interference from facilities and vertical communication elements such as stairs.

Center Pompidou by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. Photograph courtesy Rogers Stirk Harbor + Partners studio

The structural system was designed as a steel braced and exposed superstructure, with large reinforced concrete slabs.

The installations exhibited outside give scale and characterize the facades, while the elevators and escalators are a celebration of the movement of users in the building. The result is a highly expressive and strongly articulated building that has become a Parisian landmark.

The neighboring Marais district, now vibrant and multicultural, underscores the success of Pompidou's role as a catalyst for urban regeneration.

Centre Georges Pompidou, 1971-1977, Paris, France. Photograph by Michel Denancé, courtesy of Renzo Piano

Project description by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano

Concept

Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s proposal for the Centre Pompidou – a comprehensive cultural amenity and one of France’s grand projects of the 1980s – was a truly flexible container in which all interior spaces could be rearranged at will and exterior elements could be clipped on and off over the life span of the building.

The notion of flexibility is extended to every component of the building; the Centre was to act as ‘an ever-changing framework, a meccano kit, a climbing frame for the old and the young’. Conceived as a well-serviced shed, the building contains a series of uniform spaces supported externally by a free-standing structural frame, the whole capable of change in plan, section, and elevation, able to absorb the unforeseen requirements of the future.

The site for the Centre Pompidou is located in the Centre of Paris, within one kilometer of Notre Dame Cathedral and the Louvre Museum. The Pompidou Centre was planned as a key connection in the renewal of the historic heart of the capital.

The lower level of the building contains large public areas such as the theatre, shops, reception, and street-level café. Above, vast open floors house galleries, outdoor terraces, and administrative areas. Finally, the top floor accommodates a restaurant, experimental cinema, and temporary exhibitions, all of which could be open late into the night, bringing life and activity to the square during the evening.

Half the site was left unbuilt to make way for a square of civic proportions which could be used for a wide variety of community uses including markets, exhibitions, performances, circuses, games, buskers, and so on. Rue St. Martin, with its lively mix of residences above businesses, was closed to traffic to allow the cafes, restaurants, and shops to spill out into the square.

Facing the square, the west façade is given over to vertical and horizontal movement, taking advantage of spectacular views over Paris. Circulation devices – escalators, lifts, escape.

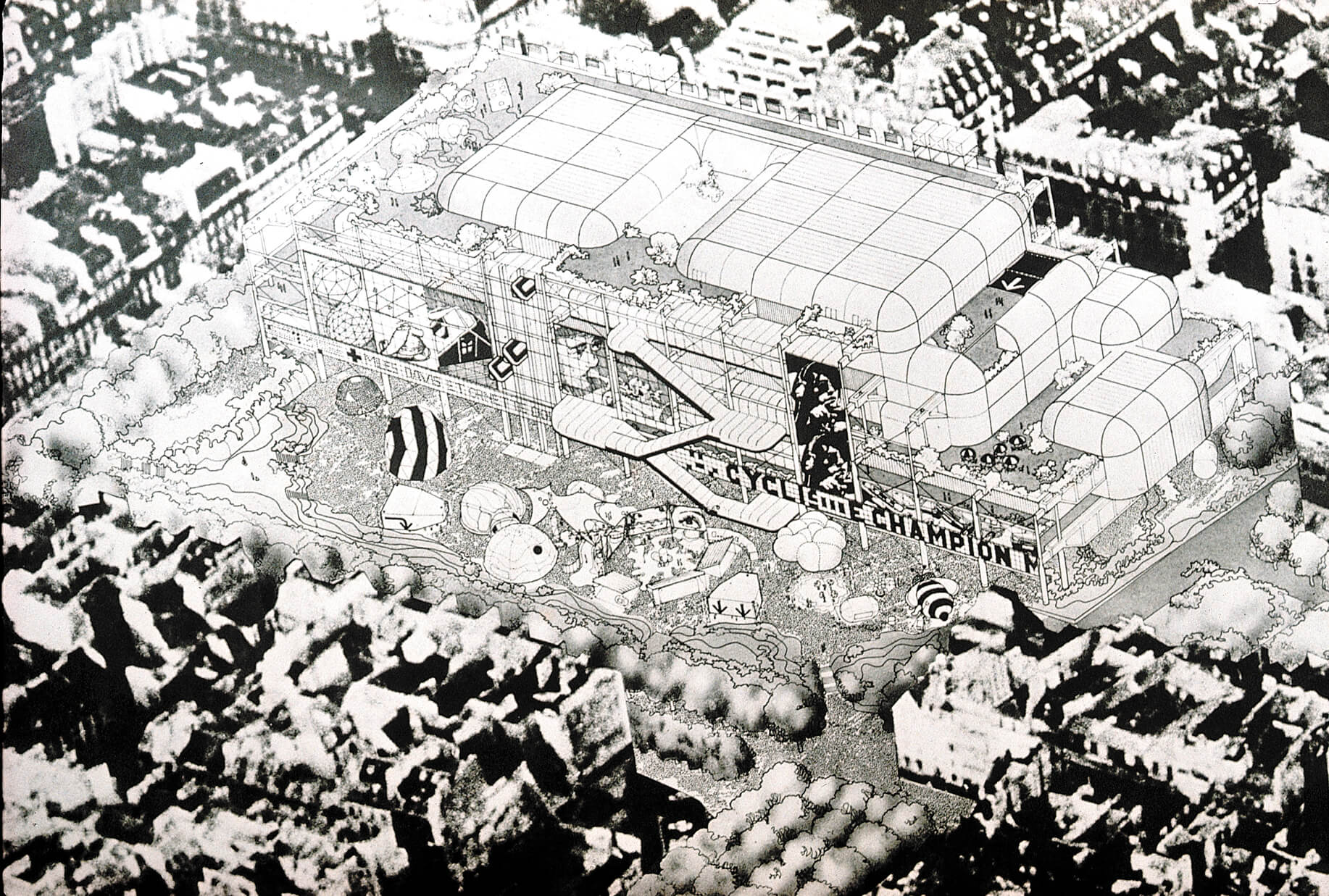

The original "jelly-mold" scene. Center Pompidou by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. Image courtesy Rogers Stirk Harbor + Partners studio

Design

The design expresses the belief that buildings should be able to change to allow people the freedom to adjust their environment as they need.

In addition, the order, grain, and scale should be derived from the process of making the building so that each element is expressed within the whole. As a result, the building becomes a true expression of its purpose. The key elements of the competition scheme remained intact as the building progressed into the developed design stage, although the interactive information façade, which was conceived as an information wall for use by the Pompidou as well as other external institutions, and the open ground floor were dropped. The building was to have had no main entrance in the traditional manner, rather a permeable ground floor where entrance to all parts of the building could be made. However, the fundamental arrangement of the building and its relationship with the city remained as the architects intended.

The entrance to the building is at the level of the street and the piazza and relates to the life of both. Alternative access is via the lifts, escalators, and staircases attached to the west façade. Each of the five major floors is uninterrupted by structure, services, or circulation.

These huge, open, loft-like spaces are serviced both from above and from the raised floor for maximum flexibility in layout. The corridors, ducts, fire stairs, escalators, lifts, columns, and bracing which would ordinarily interrupt the floors are exposed on the exterior.

Movement is celebrated throughout the building and expressed overtly in the great diagonal stair that runs up its outside and affords spectacular views over Paris. The transparency of the façade, the galleries, and especially the escalators snaking their way up the side of the building combine to reveal two captivating sights: the tiled roofs and medieval grain of Paris in one direction, and the revelation of the building – a flexible, functional, transparent, inside-out mechanism – in the other.

48-meter structures moved around the city at night. Center Pompidou by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. Photograph courtesy Rogers Stirk Harbor + Partners studio

Construction

The realization of the project was a model for interdisciplinary teamwork and was undertaken via a series of independent teams – substructure, superstructure, services, façades, interiors, systems, and the piazza – each under the guidance of a team leader, while overall coordination of the project was undertaken by Bernard Plattner.

Ove Arup & Partners, led by the great engineer Peter Rice, who had been involved in the project from the beginning, developed the structural concept for the façades, with a system that hinged on six elegantly tapered, cast-steel rocker beams known as gerberettes.

The main structure – a permanent steel grid – provides a stable framework into which the moveable parts, including walls and floors, can be inserted, dismantled, and re-positioned as necessary. The components and connections are of a scale rarely seen in the construction industry – massive steel elements were fabricated in off-site foundries and delivered by truck to the site during the night.

The six-story superstructure consists of thirteen bays and was constructed of 16,000 tons of cast and prefabricated steel with reinforced concrete floor sections. The two main structural support planes comprise a series of 800-millimeter- (31.5-inch-) diameter, spun-steel, hollow columns, each of which supports six gerberettes, or brackets.

One end of each gerberette is connected to an outer tension column, while the other supports a steel lattice beam. The stability of the building is achieved through diagonal bracing in the long façades and by stabilized end frames.

The cladding is a curtain wall of steel and glass, mixing glazed and solid metal panels hung from the floor above to keep them structurally separate from the façades, and therefore easily changed. The line of the cladding is kept back from the edge of the building, allowing plenty of space for human interaction, while lending the building an open and transparent appearance.

![Sheila Hicks presents at the Georges Pompidou Center "Lignes de vie" [Life lines]. Photography © Cristobal Zanartu Sheila Hicks presents at the Georges Pompidou Center "Lignes de vie" [Life lines]. Photography © Cristobal Zanartu](/sites/default/files/styles/mopis_home_news_category_slider_desktop/public/lead-images/metalocus_sheila-hicks_ligne-de-vie_19.jpg?h=08e4c285&itok=v-mgkVsM)