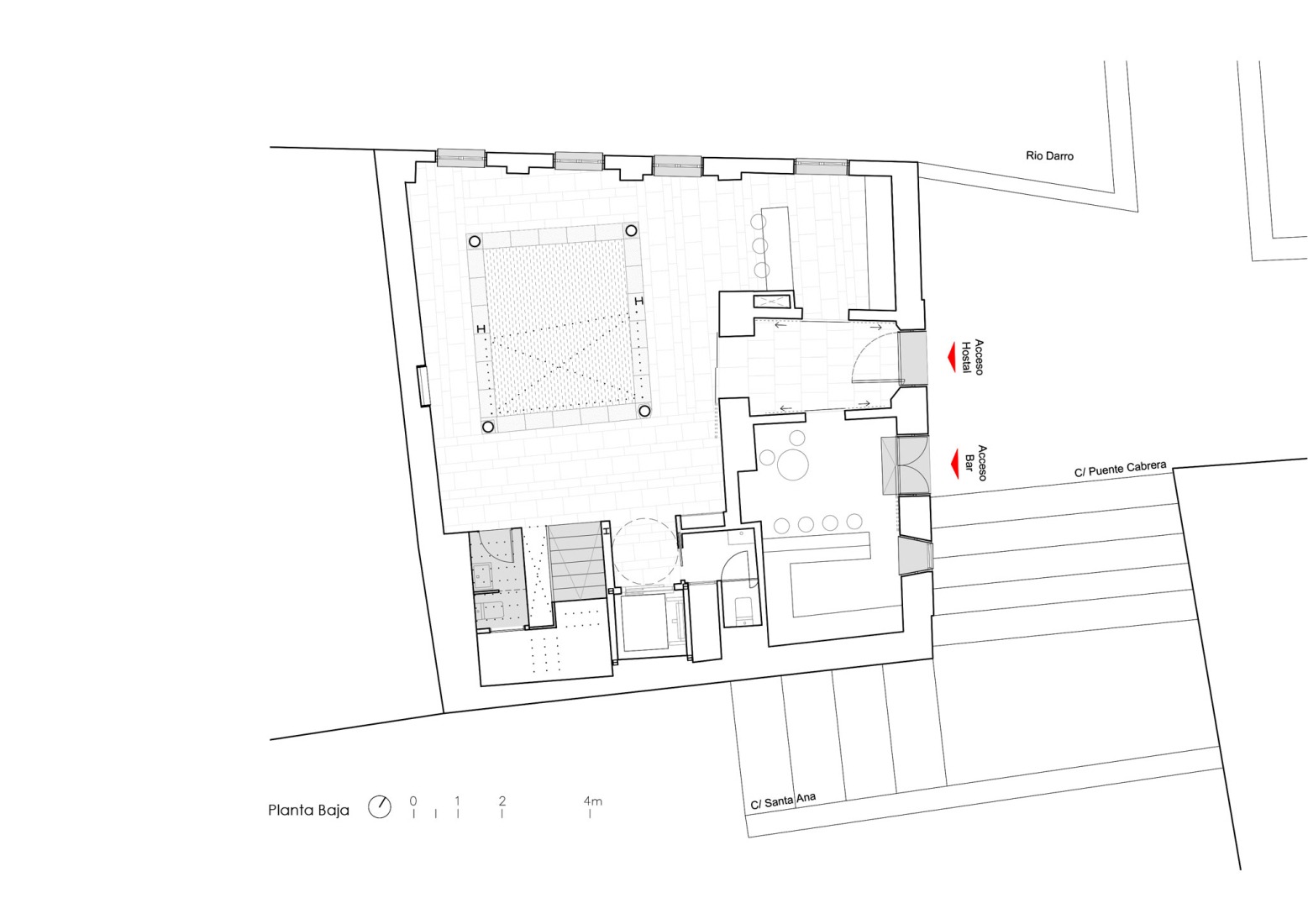

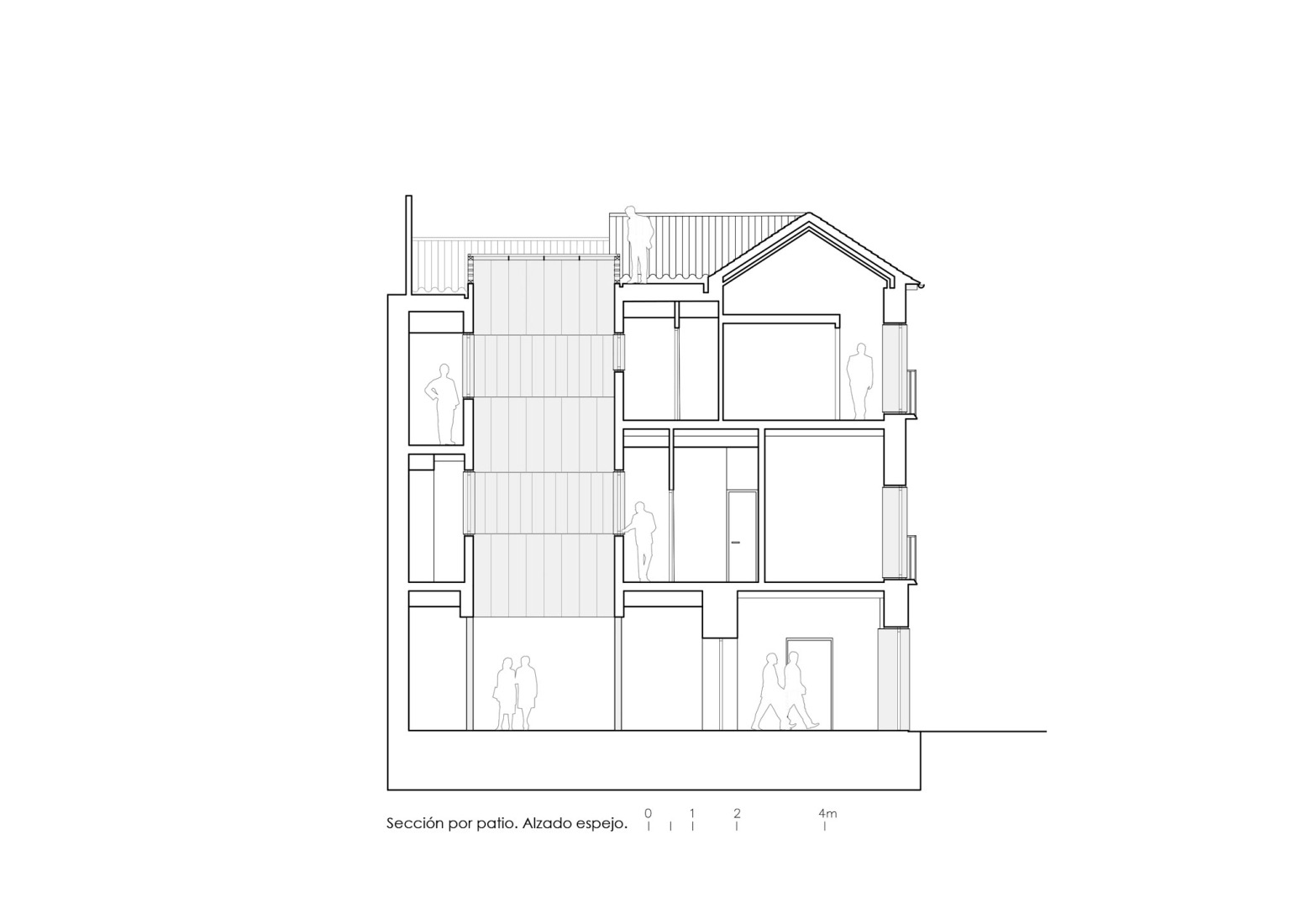

Muñoz Miranda Arquitectos’ proposal paid special attention to the recovery of the central courtyard, which was partially reconstructed using specular devices that evoke the missing section, recomposing a visual perception where past and present engage in dialogue. The intervention in the courtyard begins with the removal of a load-bearing wall from the early 20th century, built to support the extension of the upper floors over the courtyard. This frees up the ground floor and restores the view of the four original columns of the Sierra Elvira marble courtyard by inserting two HEB metal pillars that free the columns from their structural condition.

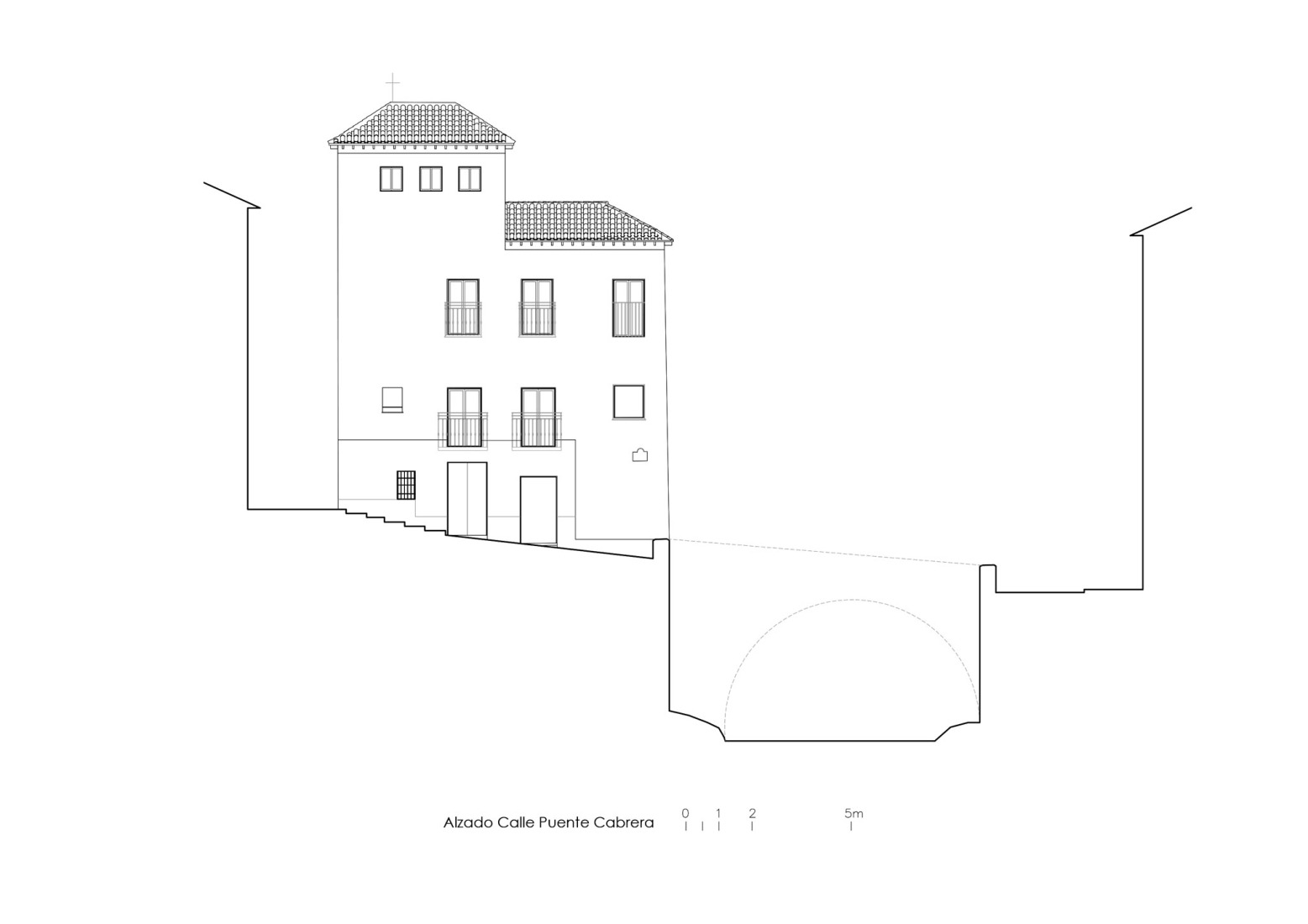

A set of complementary interventions adds to the previous ones, establishing an open dialogue with the pre-existing structure while improving the building’s structural stability, weakened by successive and indiscriminate alterations, even on the façade. These actions enrich the project and define both its aesthetic expression and its urban and architectural resilience.

Seven-room hostel by Alejandro Muñoz Miranda. Photography by Javier Callejas, Seville.

Project description by Muñoz Miranda Arquitectos

In the historic fabric of Granada, beside the sinuous course of the Darro River and at the crossroads marked by the Cabrera Bridge beneath the Alhambra, an anonymous residential building contains within its walls centuries of transformations. Its rehabilitation into a seven-room hostel is not limited to material restoration but proposes an exercise in coexistence between times, where the old and the new interlace in a precise choreography of structures, joints, and reflections. The project does not seek to conceal the trace of history or erase the scars of use, but rather to reveal, enhance, and lastly rewrite them.

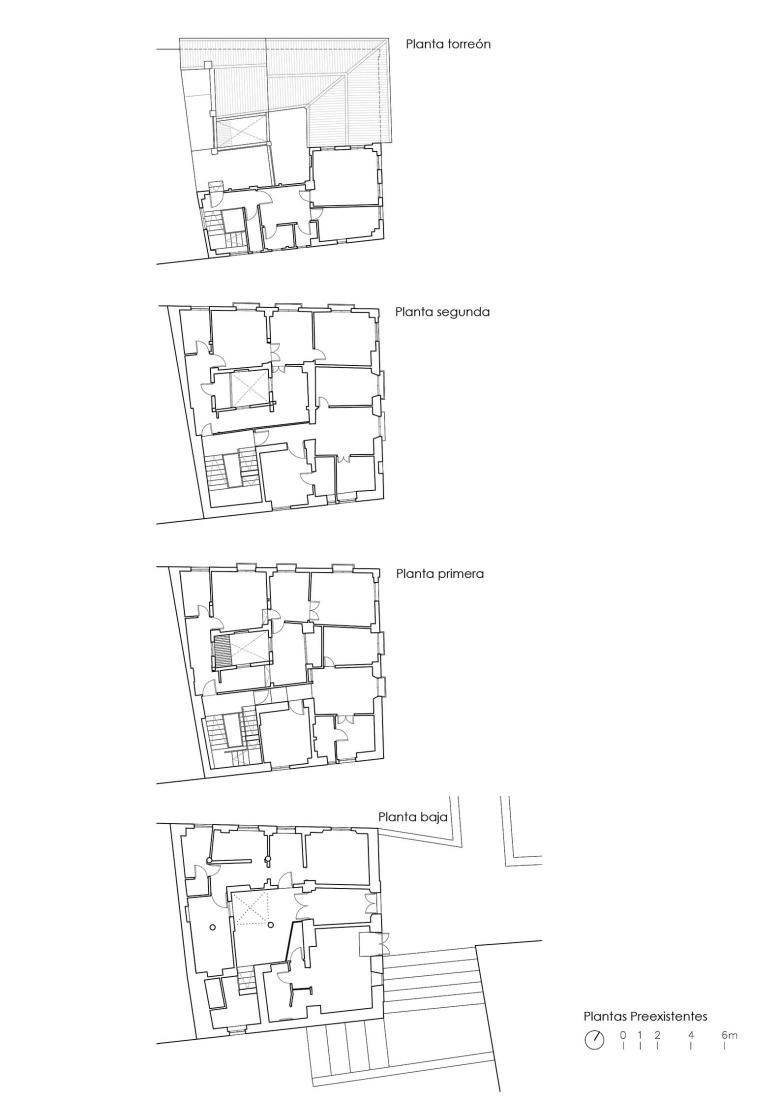

From the outset, the intervention proposes a radical gesture: remove from the building of all the superfluous additions that, over decades, had distorted the understanding of the original house. This surgical operation makes it possible to rediscover the primordial structure of rammed-earth and solid brick load-bearing walls, the timber wrought, and, above all, the central courtyard on the ground floor, now turned into the epicenter of the project. Nevertheless, the act of elimination is not absolute: the historic extension of the first and second floors is preserved, which at the beginning of the 20th century, occupied half the courtyard after the demolition—by municipal decree following a devastating storm—of the jabalcones (wooden cantilevered balconies over the river). This encroachment upon the courtyard, consolidated by the need to enlarge the dwelling’s surface, is incorporated into the narrative, accepted as yet another layer of constructive memory, introducing a specular optical effect that completes the spatial image of the courtyard.

Beneath the surface of what is visible, the building recounts its evolution through a series of “structural grafts.” Old repairs, such as riveted steel reinforcements or the occasional replacement of timber beams with double-T steel profiles, reveal a history of successive adaptations. These traces are not hidden: they are acknowledged as key elements for understanding the transformation process, like marginal notes in a manuscript corrected and rewritten time and again.

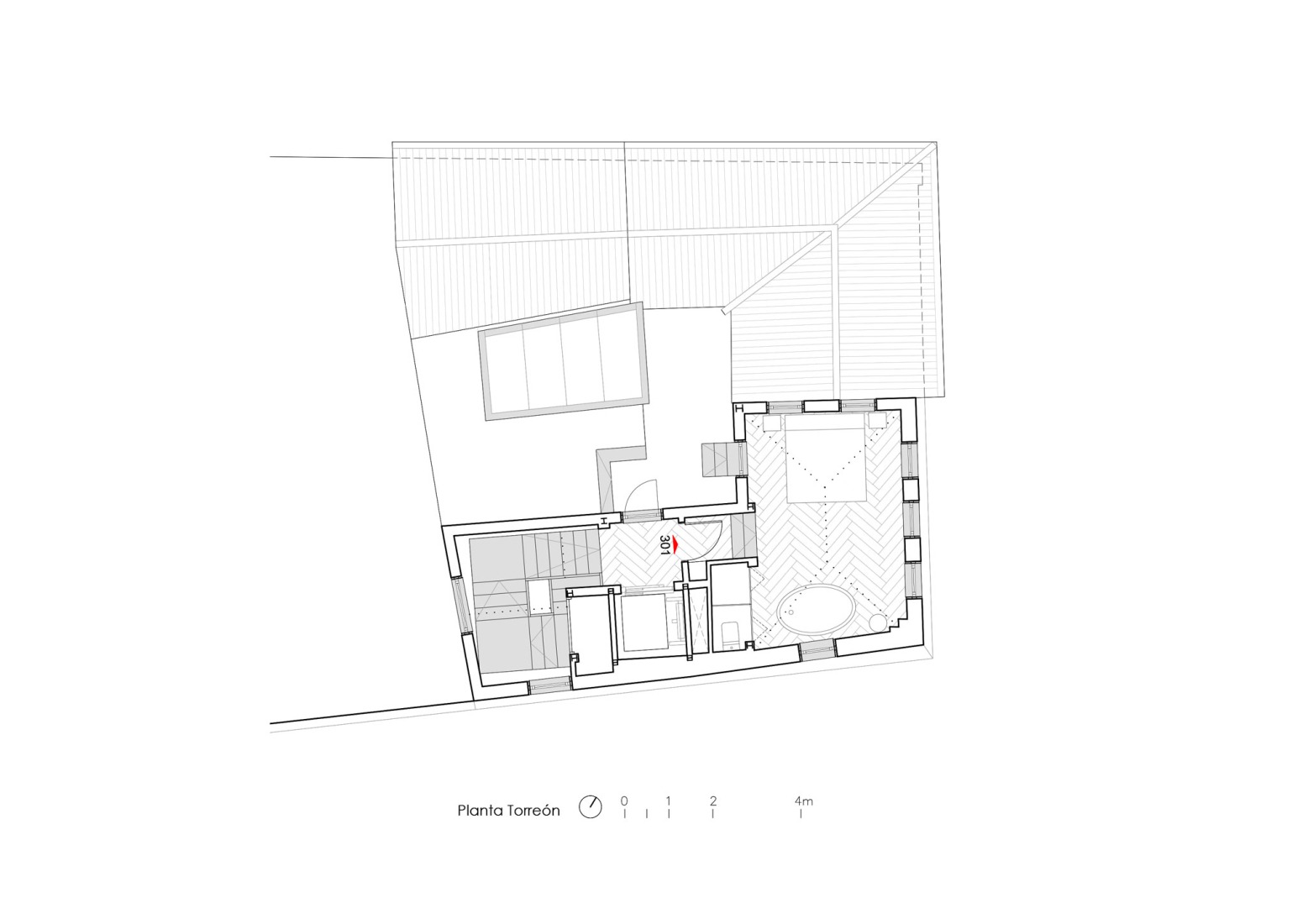

The new steel structure emerges from the heart of the courtyard as a second backbone sustaining the whole. This vertical portico system does not replace the existing fabric but rather overlays it, generating a dialogue between the lightness of steel and the massive inertia of the original walls. The encounter between both materialities becomes explicit at the building’s crown, where the metal roof of tensioned rafters rests upon the historic masonry, as if a floating structure was seeking support in the stone’s gravity. In this gesture, the idea of the tectonic joint materializes as a place of encounter and transition, joining not only materials and techniques but also historical periods and narratives.

The intervention reaches one of its most significant moments on the ground floor, where a load-bearing wall added during the courtyard’s extension is removed, thus restoring the free plan. In its place, two HEB-section steel columns reinstate the perception of the four original columns of Sierra Elvira marble that once supported the timber floors. These columns, now released from structural duty, remain as vestiges, relics of the Kunstform (art form) that Bötticher distinguished from the Kernform (core form). In contrast, the new columns assume both roles simultaneously: support and expression, technique and symbol.

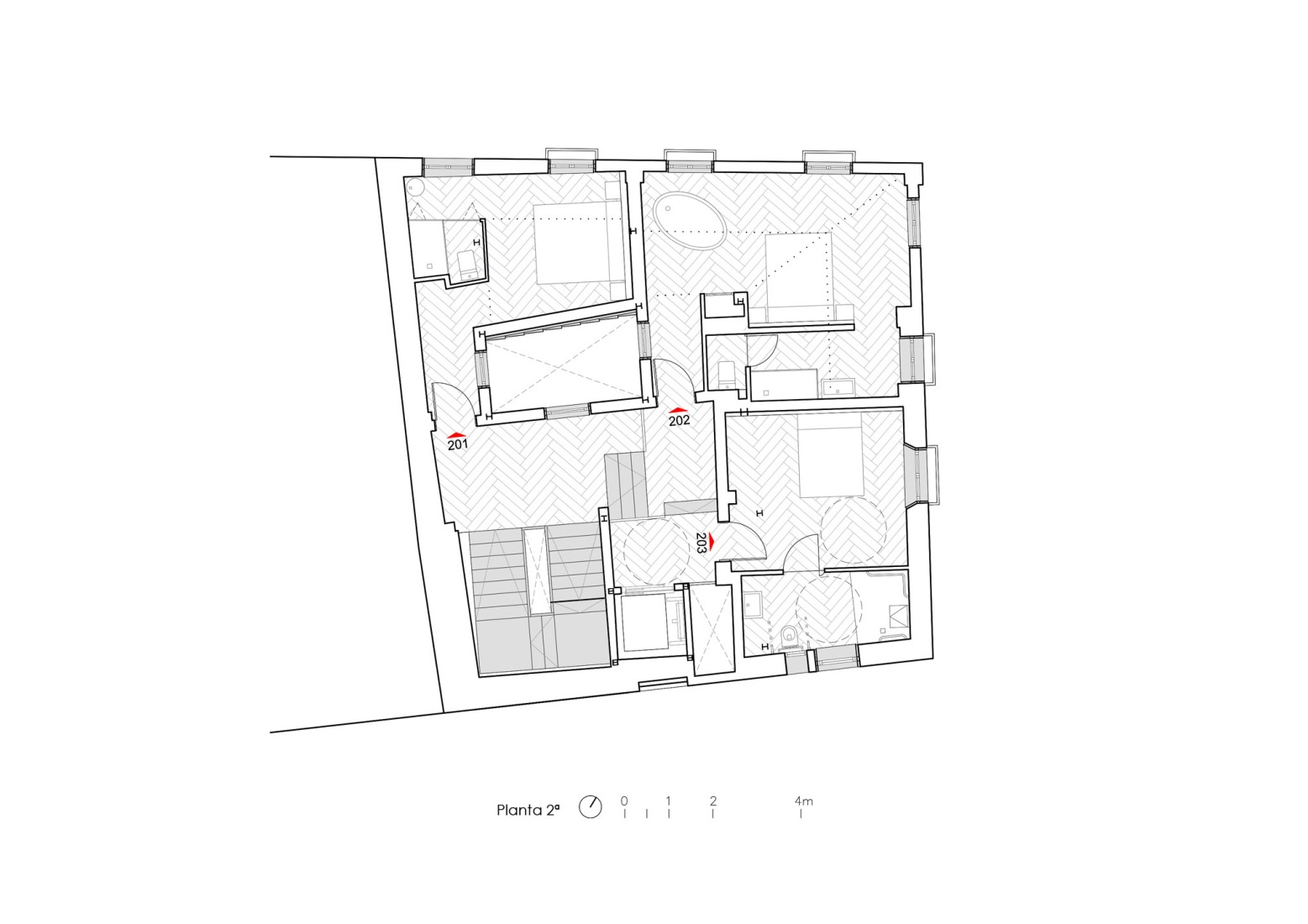

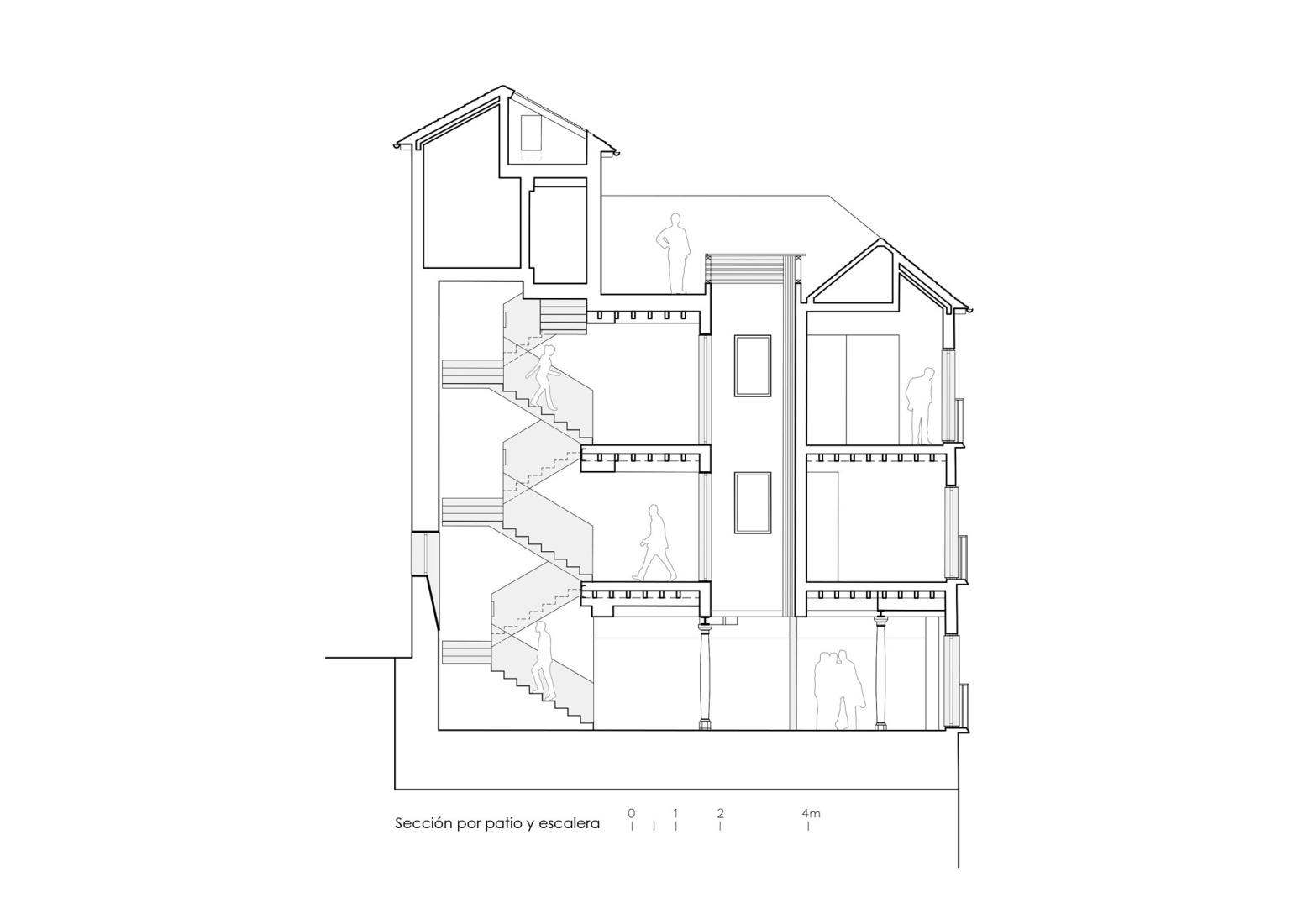

Upon these new supports rest large steel beams that, positioned above the old timber beams, sustain the rest of the building. This horizontal system integrates with the rehabilitation of the existing floors: some timber pieces are replaced with new ones, following the original technique, while all receive a reinforced compression layer with metal connectors. The result is a web of coexistences in which old and contemporary intertwine without hierarchy, allowing the structure to be read as a palimpsest.

The structural strategy also extends to the vertical circulation elements. The old staircase, deteriorated and inadequate, is replaced by a new folded steel piece, fabricated from self-supporting steel plates. This staircase not only articulates the routes but also acts as a bracing element, complemented by the steel framework housing the elevator. Together, they reinforce the seismic stability of the building while introducing a contemporary material language displayed without artifice.

Every constructive gesture reinforces the idea of material honesty. Steel profiles and plates remain exposed, joints are revealed openly, and welds and connections speak of their own technique. This frankness reaches its most eloquent expression in the framing of the façade openings. By means of steel frames embedded within the thickness of the wall, rigidity is given to an envelope weakened by the indiscriminate piercing of windows in the past. Then, the new sheet-metal linings—jambs, lintels, and sills—are subtly detached from the historic masonry, exposing accumulated deformations and tilts, and making visible the tension between stability and ruin. Here, the joint is not only a technical resource but also an ornament in the sense attributed by Louis Kahn: a manifestation of constructive logic that becomes aesthetic expression.

The project does not limit itself to solving structural issues. It also ventures into the realm of perception and memory through a poetic device: the virtual restitution of the original courtyard. Where the physical space can no longer be recovered, optical illusion is deployed. A series of serrated mirror-glass panels fragments and reflects reality, creating a simultaneous vision of what was before and what is nowadays. From certain angles, the observer perceives the orthogonal geometry of the lost courtyard; from others, the image distorts and compresses, evoking the galleries that once lined its perimeter. The courtyard roof, closed with a glazed lantern, prolongs this visual play, fusing reflections of the sky with the specular grid until forming a scene in which the past is projected onto the present.

This specular operation does not seek to deceive but to invite reflection. Opposite the tangible materiality of the new structure, the reflection evokes the intangible dimension of memory. Thus, the project situates itself in an intermediate territory, where rehabilitation is neither mere conservation nor simple modernization but critical reinterpretation. The coexistence of the physical and the illusory becomes a metaphor for the coexistence of historical times, of the massive solidity of masonry and the fragility of glass, of constructive certainty and perceptive ambiguity.

Ultimately, this intervention demonstrates that heritage rehabilitation can transcend the technical plane to become a cultural act. The superimposition of structures, the precision of joints, the transparency of materials, and the specular evocation compose a complex narrative in which every layer is recognized and respected. The building, once condemned to ruin, is thus transformed into a living space that recounts its own story—a story made of permanences and mutations, of loads and reflections. In this incessant dialogue, the past is not petrified but finds in contemporary architecture an ally to continue being present.