The Netherlands has always been at the centre of the world art and cultural scene. From the late sixteenth century and the famous Golden Age to Van Gogh, countless great names have emerged from the "Lowlands", and many more who have left their mark with works from all branches of art, and for, of course, architecture is no stranger to this.

Although Rotterdam witnessed this with works such as the Witte Huis or the Sint-Laurenskerk church (the only medieval building still standing today), the splendour of the city's architecture came with the anti-academic currents of the early 20th century, with interventions such as the Royal Maas Yacht Club of Barend Hooijkaas jr. in Michiel Brinkman (we'll talk about his son Johannes Brinkman later), with his elegant resolve associated with the Swiss-German Jugendstil.

From then on, the city began to host works of the most innovative modernity by the hand of local offices (mostly), but which would sadly be truncated by the effects of the Nazi occupation and the bombing of 1940. That year meant an important tragedy for the Roterdamers who, due to a "misunderstanding" of the war, must have seen the city centre burn, surrendered to the chaos of the passage of the armed forces towards England. Even so, the damage did not stop the Dutch city that quickly tried to recover from the tragedy, and began, before this forced clean sheet, an almost unprecedented process of urban renewal and modernization.

This opportunity represented a change concerning the role of the historical context and the remains of the industrial city, which even without being forgotten, were displaced in the face of the new urban reconstruction strategies, also necessitated by the economic urgency that the migration of companies and citizens facing these circumstances. More and better public spaces, larger mobility networks discriminated by type of transport, vertical developments, the relocation of the port (to date the largest and busiest in Europe) and changes in land use accompanied a long process of regeneration. which became consolidated almost thirty years later.

If we add to this the constant renovation processes that continue to be implemented to this day, and the privilege of even hosting large and renowned local architecture offices such as Rem Koolhas and OMA, Kaan or MVRDV, the city has gradually become the perfect canvas for architectural experimentation, a city that is never finished and, make no mistake, a city that every architect would like to have at least one chance to dance with.

With this selection we want to show at least a part of the extensive and varied architectural catalogue of Rotterdam, making a brief historical journey from the beginning of the 20th century to the present day.

1. Van Nelle Factory by Brinkman & Van der Vlugt

We start with everything! The Van Nelle tobacco, tea and coffee factory (1925), a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2014, is a work of the Rotterdamers Brinkman & Van Der Vlugt and had the collaboration of the also renowned Mart Stam. The factory is probably one of the greatest exponents of the Dutch New Objectivity, which marked a before and after for the role of Dutch architecture on the world stage and laid the foundations for Rotterdam to begin to position itself as the favourite city for experimentation architectural structures of the country.

Under a rationalist aesthetic, the project tackles with masterful quality the nascent spatial mandates of the conquests of labour rights of the time, balancing the work and well-being of the workers with open spaces, naturally lit and ventilated and leisure areas designed for these purposes, made possible by the imposing reinforced concrete structure that contains them.

Of all the architects discussed here, Oud is probably the one most associated with the avant-garde movements of the beginning of the century, but he also knew how to adhere to the precepts of the New Objectivity. This mixture is evident in the Kiefhoek neighbourhood (1925), in the south of Rotterdam, with a project that creates a constant dialogical relationship between function and poetry, between Rationalism and De Stijl.

At the time of this work, Oud, who was in the middle of the construction of Café De Unie, another of his iconic works in the city, was also in charge of the city's Housing Department. This, in part, allowed him to take some design freedoms to incorporate new space features into residential projects for workers that until now were not taken into account for public management developments.

Resolved through minimum housing for families of up to eight people (62 m2), the neighbourhood contains 294 homes, two shops, a water distillery, two warehouses-workshops, two playgrounds and a church, all resolved within a closed pre-existing enclave. with facades stuccoed in white and primary colours for the carpentry.

Although today we could not visit the original work (it was demolished in 1978), an almost exact replica was built between 1989 and 1995 by the architect Wytze Patijn. Projected in the same location and with only some changes and updates in the internal distribution of the houses, this reconstruction today allows us to delight ourselves with the housing model that was the germ with which Oud, only a year later, would begin to plan its Five houses in a row for the Weissenhof exhibition.

"The most modern department store in Europe". With that slogan people used to describe “The Hive”, the shopping centre built by Willem Dudok between 1928 and 1930 in the old Van Hogendorpsplein.

The work also continues with the precepts of the New Objectivity, with exposed brick facades and large glazed panels that, due to their reference to the port of the city, their monumentality and their vehemence, immediately turned the new building into a reference to scale. urban for the entire population until the tragic May 10 German bombing, which reduced the building to only a third and which, beyond some attempts to recover the remaining part, would finally be demolished according to the expansion plans of Coolsingel and replaced by a building by Marcel Breuer (1955), in use to this day.

Located in the Museum Park, the Sonneveld House was Brinkman & Van Der Vlugt's great return to the Rotterdam scene, having completed the Van Nelle Factory a few years earlier. The work was commissioned in 1929 and built between 1932 and 1933, for Albertus Sonneveld, one of the three directors of the Van Nelle factory.

Widely studied in canonical historiography, this work is a constructed manifesto of the New Objectivity of the Netherlands and a prodigal daughter of the architectural context of the time that condenses in its spaces the strictest concepts of European modernity, from Le Corbusier to Loos.

Unlike the previous building, the Sonneveld House is one of the survivors of the German bombing and has become, like its neighbour House Chabot (Gerrit Willem Baas, 1938), one of the examples of Dutch architecture of that better period preserved from all over the country.

Willem Dudok's De Nederlanden van 1845 building (1942) was a direct consequence of the effects of WWII on Rotterdam. Among the buildings affected by the bombing was the former headquarters of the insurance company, designed with H. P. Berlage, which, although it remained standing, the damage did not allow its recovery. At that time, in addition, Dudok was the official architect of the company and had already been in charge of the project for its headquarters in Arnhem five years earlier.

Although the work shows the turn in the architect's trajectory towards a less functionalist and somewhat more vernacular architecture, currently its glazed access gallery, its undulating roof and the open-plan interior spaces of the building have become an icon of the area. and they have granted it the title of Municipal historical monument.

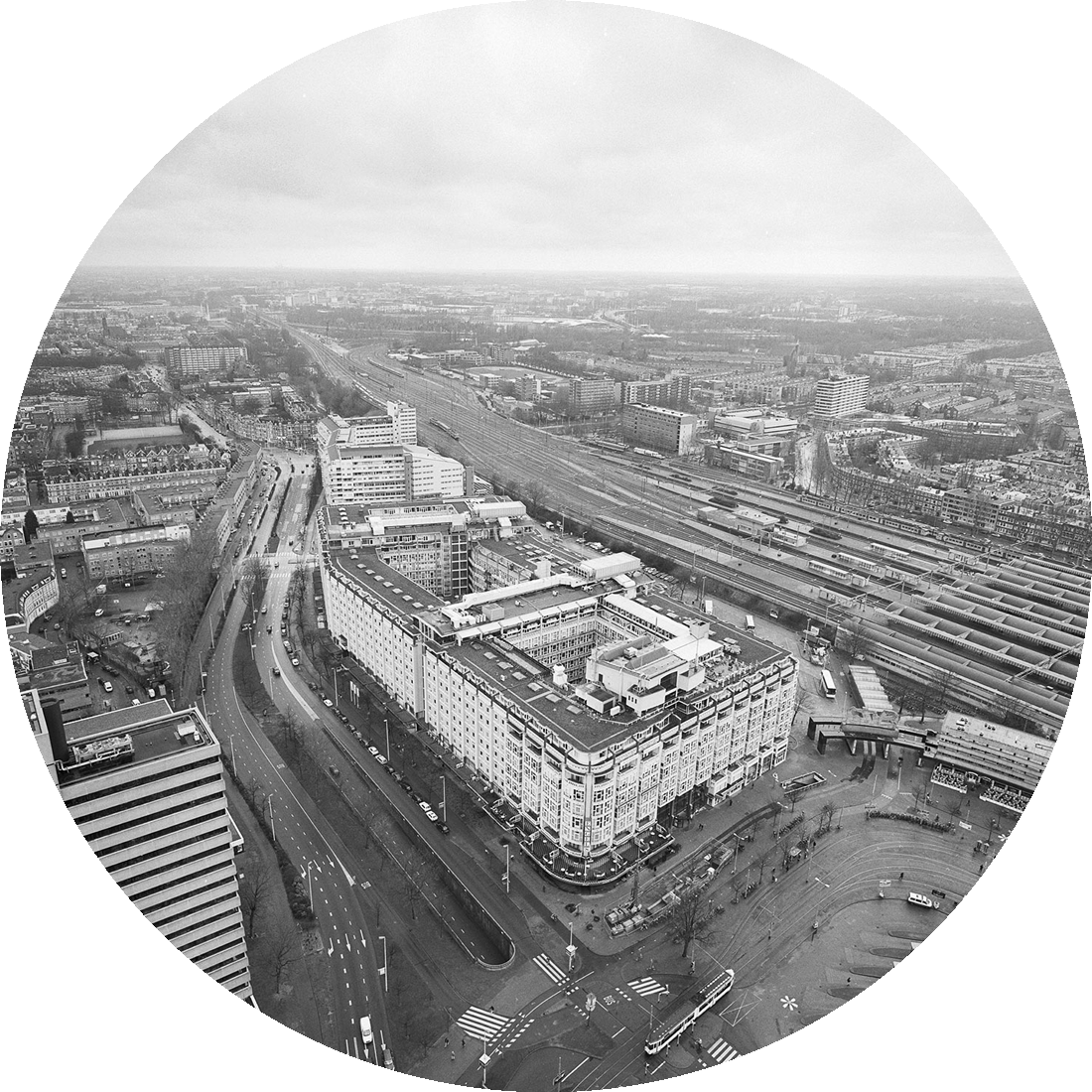

Like Dudok's previous work, the Groot Handelsgebouw (1945) is a direct consequence of the German bombing of 1940. With a historic centre in ruins, important buildings collapsed and large companies analyzing the possibilities of moving to other urban centres such as Amsterdam, the Van Tijen and Maaskant's building (who thirteen years later would build the renowned Euromast tower) was a crucial part of the city's reconstruction plan.

With a mixed investment between wholesale commercial companies, the Chamber of Commerce and the National Government, the 445,000 m² of the building came to house as many companies for the lowest possible cost.

The “Concrete Colossus”, as this icon of Dutch brutalism has been colloquially known, proposes a dynamic game of terraces between the different levels, crossed by tunnels and bridges to create a “city within the city” with internal streets of up to a kilometre that connect the more than 150 commercial premises within this monumental piece of precast concrete.

In the heart of Rotterdam, in the renovated Blaak area, are the Cube Houses by Dutchman Piet Blom (1978), probably the most visited and recognized tourist attraction in the city.

A forest of dwellings within the city, framed in an architecturally laden context with the Markthal by MVRDV, the Church of Saint Lawrence, the Central Library (1977) by Broek & Bakema and, occasionally, a colossal Ferris wheel that provides incredible views of all of Rotterdam.

The work is part of the extravagant local postmodern repertoire, which also includes the library or the police headquarters of Maarten Struijs (1981), among others, and which stands out for the 38 houses made up of inclined cubes raised above ground level, which act as a park and a pedestrian bridge that crosses one of the most congested avenues in the city.

The project was the result of a long process of morphological-functional experimentation by the architect and is part of a larger-scale complex that includes the Blaaktoren (The Pencil) and the 250 Spaanskade homes, located just as the top of the Cube Houses in front of the head of the Maas river.

The Kunsthal Museum (1987-1992) was one of the earliest and most important works by local architect Rem Koolhaas and OMA.

Rehabilitated in 2014 by the same authors, the museum is located at the southern end of the Museum Park, which it shares with other iconic works of the city such as the aforementioned Sonneveld House and Chabot House, and which receives its name precisely from of the triad formed by this museum, the Het Nieuwe Instituut and the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum.

The work is organized around ramping floors that cross the prismatic volume from one end to the other like a plaza, distributing its 7,000 m2 between exhibition spaces, an auditorium, a restaurant and offices.

The Kunsthal is located almost indifferently in front of its complex surroundings (the Maasboulevard on one side and the park on the other), but not in a sense of dispute, but rather in that of letting its surroundings be, a characteristic that, over the years, it would be accentuated with the new works in the area, following in the footsteps of what, in the words of its authors, is a true “exhibition machine”.

The park also arose as part of the commission to OMA which, together with Yves Brunier and Petra Blaisse (Inside Outside), created a linear park defined by different spatial instances with interventions by other collaborating artists, responding to the different uses proposed for each of them.

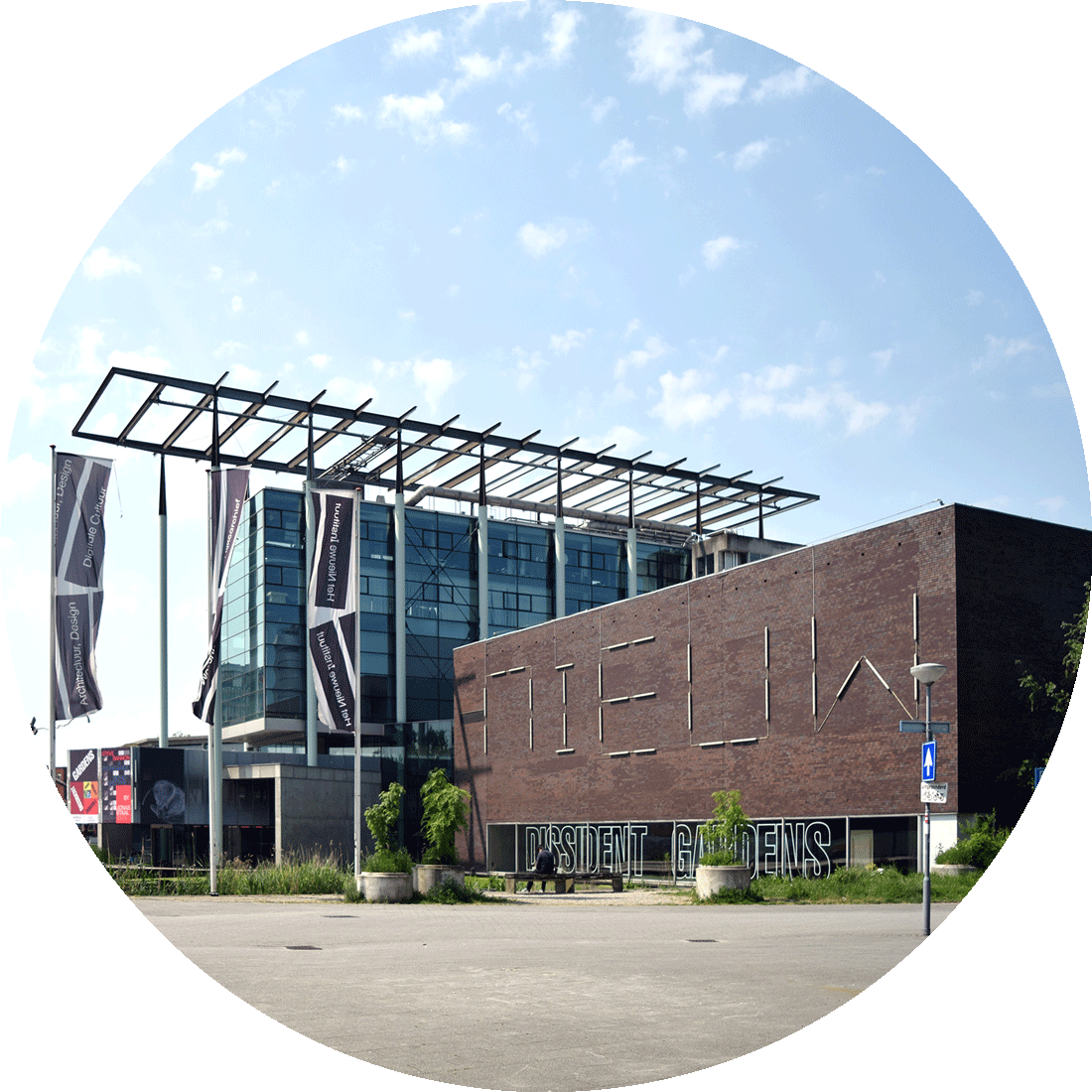

Just one year after the beginning of the Kunsthal, a competition was launched for the new building of the Het Nieuwe Instituut in the same park, an institution that condensed the functions of various bodies linked to art, architecture and culture. The team led by Rem Koolhaas was also invited to participate in the event, but despite the fact that their proposal has been widely celebrated by critics, the award-winning project and commissioned to build the brand new building was that of Jo Coenen, a country architect who he was beginning his career in construction.

This undeniably postmodern work earned Coenen international recognition and multiple awards, although eventually his career would be limited to works of a smaller scale and impact than his debut feature.

The institute is built from four simple volumes that vary from curved morphologies to perfect cubes, composed of a great variety of materials (brick, glass, steel, concrete, glass bricks) that intersect and juxtapose to generate different spatial instances that start opening on their way to the Museum Park.

The 1990s were not particularly relevant for Rotterdamer architecture, with few exceptions in the port area of Kop van Zuid. For this reason, we decided to make a jump in time of a few decades to go to the moment of splendour of the contemporary architecture of Rotterdam.

The studio based in the same city MVRDV, already had a significant number of works in the Netherlands and even abroad by then, but Book Mountain and the Library District (2012) would be the first large-scale work in the city del Maas (or at least in its metropolitan area).

With its almost 10,000 m2, the new Spijkenisse library is located in the historic centre of the town, on the market square, opposite the village church.

The library stands out with its morphology and scale compared to an environment of minor trends in height, and with a large glass roof that simultaneously tries to awaken the historical memory of the place, referring to the traditional Dutch farms typical of the area, and on the other, simulate a large mountain of stacked books that also contrast with the surrounding buildings based on the choice of materials such as exposed brick that completely cover all the facades of the new neighbourhood.

Sharing a dividing wall with Breuer's De Bijenkorf, Wiel Arets Architects was commissioned to design a tower of homes and businesses (2013) that unreservedly faces Rob van Erk's Beurs-World Trade Center (1986) on the other side of Coolsingel.

The building is made up in a tripartite way, from volumes whose distribution responds to the internal functions of the building. A basement-like block that contains the commercial functions and opens onto the Beurstraverse, an underground commercial promenade that also connects through tunnels with the metro stations, and two upper blocks of houses that are slightly out of phase with each other to generate the terraces and balconies for the residences, distributed in 54 studios, in the lower volume and 24 apartments above.

At the foot of the building, there is also the historic pedestrian shopping area of Lijnbaan (national historical heritage), a manifesto of the positions of Team X in relation to the recovery of the street as a social space, projected by Van den Broek & Bakema and inaugurated in 1953. This is considered the first pedestrian street designed for this purpose in Europe and was built as a replacement for the old commercial district that had been destroyed during the bombing of 40.

Right in front of the building, across the Beurstraverse, there is also a controversial long-term construction site by OMA for the City Forum, which started in 2008, on the former ABN Amro bank building (historical monument) and which has not yet been able to be finalized by various problems and oppositions on the part of the population.

Rotterdam has, since 2013, the five tallest buildings in the Netherlands, four of them located in Kop van Zuid and they count the signature of internationally renowned architectural firms. But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Since the post-war reconstruction period, Rotterdam has voluntarily chosen to decentralize administrative, commercial and cultural functions in different atomized nodes throughout its entire urban fabric, to the point that it is almost impossible to recognize one area as the center real city. It could be the Cool area as the administrative and business centre with works such as the aforementioned Groot Handelsgebouw, the Central Station (2014) by Benthem Crouwel Architects, MVSA Architects and West 8, the twin towers of Delftse Poort, or the two striking interventions by Will Alsop, Calypso (2009) and Pauluskerk (2013). However, the Beurs area could also be considered as the centre of a more commercial and administrative nature, or why not Blaak as the cultural and tourist centre of Rotterdam. For several years now, the port district of Kop van Zuid, in the south of the city, has concentrated a significant number of offices, homes, shops and cultural spaces, which endow this sort of island with the characteristics of an urban centre of relevance.

The most direct way to get there is by crossing the Erasmusbrug (1996) by Ben van Berkel and Caroline Bos (UNstudio), an iconic bridge that acts as a prelude to what awaits when you reach the other side.

Renzo Piano (KPN Building, 1997), Foster & Partners (World Port Center, 1998), Mecanoo (Montevideo Tower, 2003), Alvaro Siza (Torre Nueva Orleans, 2007), JHK Architecten (Unilever, 2007), and of course, OMA (without considering those who are building in the place such as MVRDV and MAD) all have a work on this island that is often referred to as the Manhattan of the Maas.

Of all these works, De Rotterdam was the last to disembark on the island (1997-2013), at the wide Wilhelminapier quay, and like several of the previous ones that took their name from the city where the ships of the docks, De Rotterdam does it from one of the Holland America Line ships that departed from that port.

The project commanded by Rem Koolhaas, Ellen van Loon and Reinier de Graaf consists of three displaced towers that reach 150 m in height, entirely covered in a glass skin. The proposal was conceived as a vertical city, and precisely for this reason it contains a great diversity of uses that go from a hotel to shops, restaurants, conference rooms and even a city council headquarters.

If we continue to the southwest, a little more on the outskirts of the city, we come across the new Hoogvliet campus by Wiel Arets Architects (2014), a complex of six buildings of more than 41,000 m2 that houses academic and social functions such as a sports centre, an art studio, a security academy, 100 housing units within a building, and two schools.

The set is unified by means of a rather neutral exterior aesthetic, in white tones and with frosted glass, in contrast to interiors where the circulations of enamelled glazing steal the attention of users.

Returning to one of the city centres, more specifically the Blaak area, we find one of the most recent works of high tourist impact in the city, the Markthal by MVRDV (2014).

A market disguised as a block of flats, or a residential complex with an air of community life? It would be very difficult to find an answer according to this question, although it is probably not necessary to know it either. The truth is that following a new national law that prohibited the sale of meat and fish outdoors, the Rotterdam city council organized a competition in 2004 to create the first covered market in the Netherlands. This proposal came to replace these functions that were previously concentrated just outside where the building is today, in Binnenrotte, the largest open-air market in the country, where thousands of people pass every Wednesday and Saturday in search of local products or, perhaps, just looking for a little flâneur.

The market hall has as its generatrix a colossal horseshoe arranged vertically, displaced on one of its axes like a barrel vault. Or, at least, it seems. Since the building, without necessarily being a horseshoe, does appear so due to the distribution of its functions, with shops and homes that surround it, and a glass core (the largest independent glazed structure in Europe) that penetrates it, thus generating the area From the market.

It is precisely the “exterior” floors and walls of the houses that float above the market, on which the iconic mural “The Horn of Plenty” by Arno Coenen and Iris Roskam was made, which covers the entire interior facade of the building with colourful fruits, vegetables and other herbs.

Although both markets currently coexist, the reality is that those who at the time sold meats in Binnenrotte are not those who are today in the Markthal since, in their functions, perhaps due to the rental costs or due to the demands of the high tourism it receives every week, the interior of the building has become a commercial centre for organic products, covered in logos of national brands and franchises (and some not so much), and those who traded outside, laws or not, continue to do so.

Towards the north of the city, passing the lakes of Hillegersberg, Planet Lab Architecture, based in Rotterdam and led by Simone Drost, has carried out the Maximaal Comprehensive Child Care Center (2014).

The work, made up of three wings that converge in the centre almost like a panopticon, is designed to house people between 0 and 20 years old with intellectual disabilities, in order to provide them with initial, primary and secondary education, in an environment in constant dialogue with the nature that surrounds it.

The building also tries to stimulate its students through sight (and other senses) and for this it uses bright colours and textures that change as the tour progresses and users enter the sensory experience. of the proposal.

There are not many rehabilitation and intervention works on historic buildings on this list. But the one that cannot be left out, in any way, is the new headquarters for municipal offices designed by OMA between 2009 and 2015. In addition, it houses different functions that range from shops, apartments, parking lots and the Museum of Rotterdam.

The work is coupled with the old Stadstimmerhuis building by JRA Koops (1947) opting for a clear contrast ratio, with cubic glass volumes that are terraced like pixels almost pyramidal towards the highest part of the building.

The OMA building, which emerged from a closed competition organized by the municipality, which invited, among others, Mecanoo, Kaan and SeARCH, also acts as an auction to the perspective from the Stadhuisstraat street, on which the city hall of the town.

Located in the vicinity of other important works such as the post office, the police headquarters, or De Nederlanden van 1845, Timmerhuis arrived to promote an area of high historical value as part of an important urban renewal process that also includes the expansion of the entire Coolsingel avenue.

Just two blocks from the Timmerhuis, the ZUS studio managed to carry out the first Luchtsingel collective financing project (2011-2015) through a crowdfunding initiative presented at the 5th International Architecture Biennale.

The work consists of a photogenic pedestrian bridge that connects three of the urban centres of Rotterdam by means of a structure of 400 linear meters perched on new public spaces and green areas that try to give a new life to areas planned for vehicular traffic and recover the synergies of urban life.

The wooden walkway connects the Het Schieblock Werkhotel, a coworking space and entrepreneur's laboratory that contains Europe's first urban agricultural roof on its roof, with Delftsehof and Pompenburg, a favourite area for Rotterdamer nightlife and a children's playground, respectively. These three interventions were also projected by ZUS, and they became one of the keys that encouraged the bridge project.

If we turn towards the Kop van Zuid area, just opposite, crossing the Rijnhaven, is the Fenix Food Factory, a classic of the city's summer season in the growing Katendrecht district.

This warehouse, built in 1922 for the Holland America Line, has been part of several renovations throughout its one hundred years of life, until finally, between 2009 and 2013, it came into operation again with one of the most visited food markets and artisan products in the city.

From the initiative to recover the uses of the area and revitalize this port district of Rotterdam, Mei architects and planners was in charge of projecting Fenix I (2019), a reform of the spaces of the warehouses, in conjunction with a vertical expansion of the building 45,000 m2.

The proposal contains, in addition to 200 homes, workspaces for the offices that already existed in the place, shops and a large cultural area. All this organized under a clear contrast between the preexistence and the new construction, a heavy industrial structure of concrete and bricks in front of a careful intervention of glass and steel, which seems to even want to detach itself from the old building with the diagonals that support the cantilevers on the old cover.

In the coming years, an intervention by the renowned MAD Architects studio (its first of a cultural nature in Europe) is also willing to carry out, to contain, under an aesthetic very faithful to its avant-garde style, the city's Migration Museum. So whether it's to soak up Rotterdamer culture, find new perspectives on the Manhattan of the Maas, or enjoy one of the many varieties of stroopwafels that the market offers, Katendrecht is a must-see in the city and one that promises to continue growing with the weather.

We are once again at the centre of architectural experimentation in the city, the Museum Park. There we can find the recently opened Depot (2020) of the local MVRDV office. An art deposit for the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum (which also foresees a Mecanoo intervention for the years to come) born from a closed competition which, after several legal twists and turns, was won by the Rotterdamers.

The project draws attention for its bowl shape, but on a colossal scale that easily surpasses its classic neighbours, except, of course, for the iconic brick tower of the museum to which it responds.

The building has 14,000 m2 with public and private exhibition areas, as well as various annexed areas for complementary uses such as offices, logistics, among others.

If its shape is already striking, its full cladding in mirrored glazing reflecting a distorted image of the park and its architecture, and even its large garden terrace with medium-sized trees, the interior of the building is not far behind. An atrium with stairs that intersect in a pas de deux while they ascend to the highest part of the bowl and invite us to delight ourselves with each of the works exhibited on the same walls that mark the route.

Finally, a work that has not yet been built, but that we will be able to see in the coming years and that, without a doubt, is going to be talked about (or will continue to do so); OMA's Feijenoord City master plan started in 2016.

The project commanded by David Gianotten has been developed in collaboration with the promoter Stichting Gebiedsontwikkeling aan de Maas, the City of Rotterdam, the Feijenoord Stadium and several other stakeholders, and comes to revitalize Rotterdam Zuid, one of the great forgotten of the planning of the city and historically in need of an economic boost and integration to the rest of the urban fabric.

Located on the banks of the Maas River, the plan includes the creation of a new stadium for the city's soccer team, four residential towers, a hotel and the development of the northern part of the urban strip, as well as new public and commercial spaces and an intervention on the area surrounding the current De Kuip stadium. All this distributed in eight general interventions (Stadskant, Waterfront, Mallegatpark, New Stadium, De Strip, De Kuip / Kuip Park, De Veranda and Tidal Park) and concentrated in a total of 592,000 m2 that will try to revitalize and reconnect this area and incorporate it into the rest of the city.